Advancements in the field of bone and mineral research have underscored the critical role of molecular and biochemical indicators in early detection and management of skeletal disorders. Through a combination of laboratory assays, imaging techniques, and genetic profiling, clinicians can now access a wealth of data that enhances patient care. This article explores the diverse range of tools—collectively known as biomarkers—that inform our understanding of bone health, highlight pathophysiological processes, and support personalized treatment strategies.

Biochemical Markers in Bone Remodeling

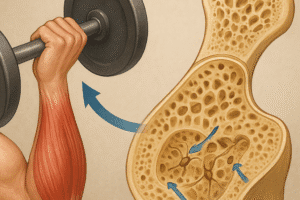

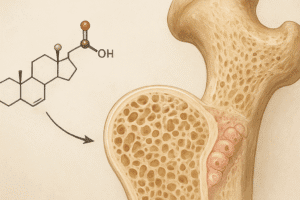

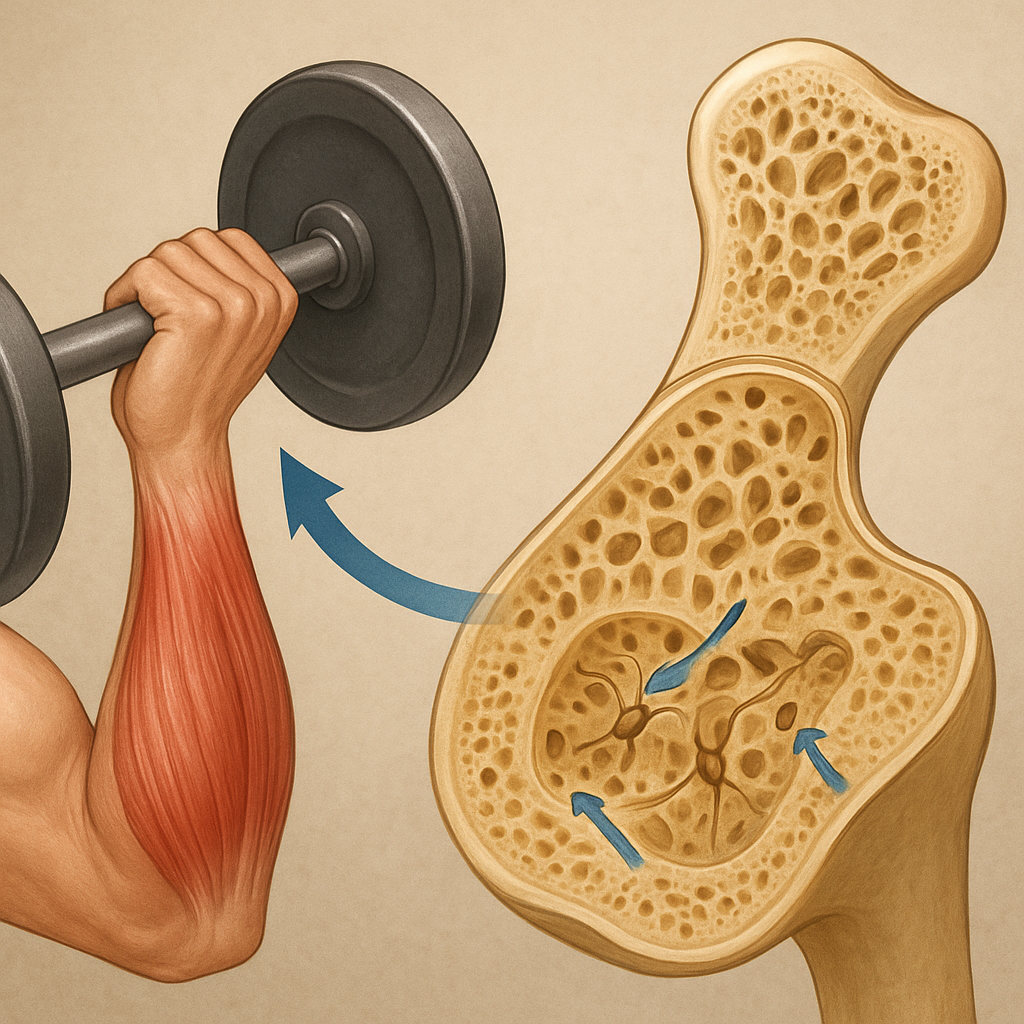

Bone tissue undergoes continuous renewal through the coupled actions of formation and resorption. Disruption to this balance can lead to conditions such as osteoporosis, osteomalacia, and Paget’s disease. Monitoring specific molecules released into blood or urine during these processes enables real-time assessment of skeletal turnover.

Bone Formation Markers

The synthetic and secretory activities of osteoblasts yield several measurable proteins and enzymes:

- Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP): An isoenzyme produced by active osteoblasts, BSAP correlates directly with mineralization rates.

- Osteocalcin: This non-collagenous protein binds hydroxyapatite in the matrix, reflecting osteoblastic function when detected in serum.

- Procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP): Released during collagen synthesis, P1NP serves as a reliable indicator of new bone formation.

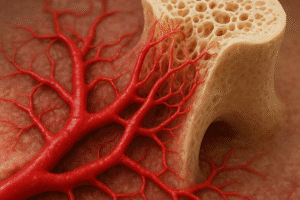

Bone Resorption Markers

Markers of matrix degradation are generated when osteoclasts degrade collagen and other matrix components. Commonly assessed molecules include:

- CTX (C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen): Elevated levels in serum or urine signal increased resorptive activity.

- NTX (N-terminal telopeptide): Another collagen breakdown fragment used to monitor therapeutic response in antiresorptive treatments.

- Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRACP 5b): Derived from osteoclasts, TRACP 5b concentration provides insight into osteoclastic numbers and function.

Clinical Applications in Diagnosis and Monitoring

Clinicians integrate biomarker data with clinical evaluation to refine risk assessment, guide therapeutic choices, and track treatment efficacy.

Risk Stratification and Early Detection

Traditional assessment of fracture risk relies on bone mineral density (BMD) measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). However, incorporating turnover markers can uncover high-risk individuals whose BMD may not fully reveal active disease. For example, a patient with normal BMD but significantly elevated CTX may warrant earlier intervention to prevent bone loss.

Guiding and Evaluating Therapy

Monitoring changes in serum or urinary markers helps tailor and optimize treatment regimens. Antiresorptive agents such as bisphosphonates and denosumab typically suppress CTX and NTX levels within weeks of initiation. Conversely, anabolic therapies like teriparatide increase formation markers such as P1NP and BSAP prior to observable gains in BMD.

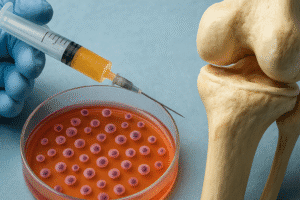

Non-Invasive Alternatives to Biopsy

While bone biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing certain metabolic disorders, its invasiveness and sampling limitations have prompted research into surrogate markers. By analyzing a panel of biochemical indicators, clinicians can often forgo biopsy, achieving high diagnostic confidence through cytokines, growth factors, and matrix degradation products.

Emerging Biomarkers and Future Directions

Next-generation techniques promise to deepen our mechanistic insights and expand diagnostic capabilities beyond conventional markers.

Circulating MicroRNAs

Small non-coding RNAs regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally and can be detected in blood. Specific microRNA expression profiles correlate with osteoporotic fractures and bone metastasis, offering a minimally invasive approach to identify molecular signatures of disease.

Genetic and Epigenetic Indicators

Genome-wide association studies have identified polymorphisms in genes encoding collagen, vitamin D receptors, and Wnt signaling components that influence bone mass and quality. Epigenetic modifications—such as DNA methylation patterns in osteogenic genes—represent an additional layer of regulatory control potentially amenable to pharmacological manipulation.

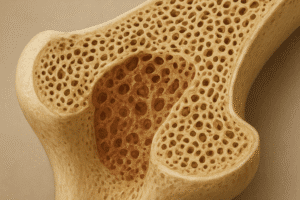

Advanced Imaging Biomarkers

Quantitative computed tomography (QCT), high-resolution peripheral QCT (HR-pQCT), and magnetic resonance techniques now offer three-dimensional evaluation of trabecular architecture, cortical thickness, and bone marrow composition. Image-derived texture and density metrics function as indirect biomarkers of microstructural integrity.

Challenges and Considerations in Biomarker Analysis

Despite their potential, the translation of biomarkers into routine practice encounters several hurdles:

- Biological variability: Circadian rhythms, dietary factors, and renal clearance influence circulating concentrations. Strict timing and standardized sample handling are crucial to reduce preanalytical variation.

- Analytical precision: Assay sensitivity, reagent quality, and inter-laboratory calibration affect reproducibility. Adoption of international reference standards remains a priority.

- Clinical interpretation: Single-marker assessments may provide limited insight. Multiplex approaches and composite scores integrate formation and resorption indices, improving predictive power for fracture risk and treatment response.

- Cost-effectiveness: Widespread screening with expensive molecular assays raises economic concerns. Health systems must balance innovation with affordability and accessibility.

Overall, the integration of established and novel markers offers a multifaceted strategy for bone disease diagnosis and management. Ongoing research efforts aim to refine assay accuracy, uncover new molecular targets, and personalize therapeutic interventions based on individual risk profiles.