The exploration of the bone–cartilage interface unveils a complex anatomical niche where two distinct tissues converge to maintain joint function and integrity. This region is pivotal for load distribution, shock absorption, and metabolic exchange. Recent research has shed light on cellular behavior, molecular pathways, and mechanical properties that define this transition zone. Understanding its biology and pathology is essential for developing innovative treatments for degenerative diseases such as osteoarthritis and for advancing tissue engineering strategies.

Structure and Composition of the Interface

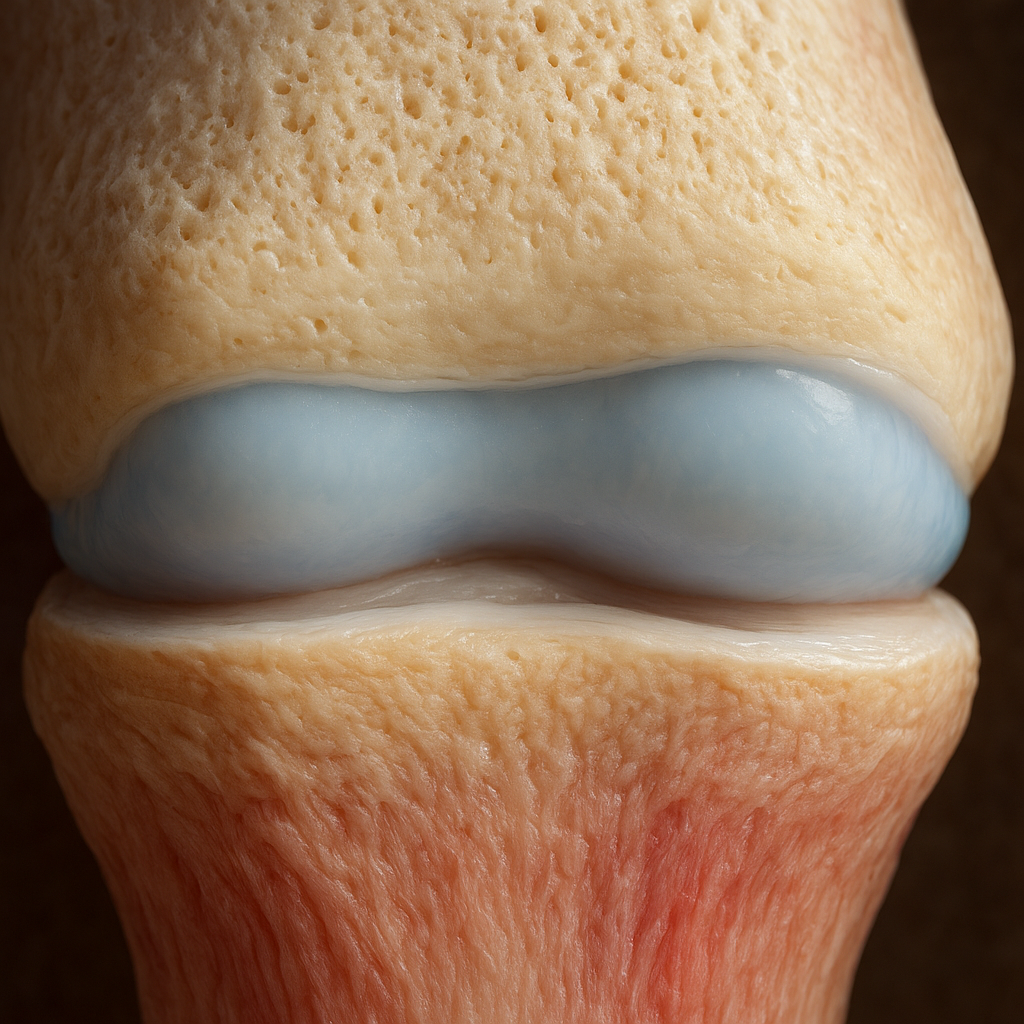

The bone–cartilage interface, often called the osteochondral junction, comprises multiple layers, each with unique cellular and extracellular features. From the articular cartilage surface down to the subchondral bone, gradients in composition and mechanical properties enable seamless load transfer and joint resilience.

Articular Cartilage

Articular cartilage is a specialized connective tissue with a high water content and a robust extracellular matrix composed primarily of collagen type II and proteoglycans. Key features include:

- Chondrocytes that maintain matrix homeostasis and respond to mechanical stimuli.

- A multi-zonal architecture: superficial, middle, deep, and calcified cartilage zones.

- Low cellular density but high metabolic activity in response to injury or degeneration.

Calcified Cartilage and Tidemark

This transitional zone acts as a semi-permeable barrier between cartilage and bone. It is characterized by:

- A highly mineralized matrix providing mechanical anchorage.

- An ultrathin layer called the tidemark, which is critical for preventing vascular invasion into the cartilage.

- Gradients in stiffness facilitating stress distribution across the interface.

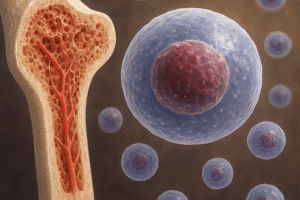

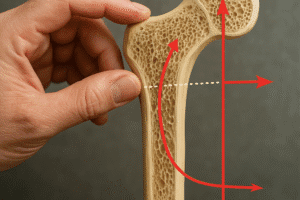

Subchondral Bone

The subchondral bone lies beneath the calcified cartilage and consists of cortical and trabecular regions. Salient features are:

- Osteoblasts and osteoclasts orchestrating bone remodeling.

- An intricate vascular network for nutrient supply and waste removal.

- A highly organized collagen type I matrix conferring rigidity and support.

Biomechanical Function and Significance

The biophysical attributes of the bone–cartilage interface determine its response to mechanical loads and its capacity to dissipate stress. Alterations in these properties often underlie joint degeneration and pain.

Load Distribution

When joints bear weight, articular cartilage deforms and redistributes forces to the subchondral bone. The interplay between soft cartilage and rigid bone involves:

- Viscoelastic behavior of cartilage enabling energy absorption.

- Elastic recoil of subchondral bone contributing to joint stability.

- Dynamic fluid pressurization within the cartilage matrix.

Shear and Compression Resistance

The osteochondral junction must resist both shear forces during movement and compressive loads during standing or jumping. Factors include:

- Gradient in modulus of elasticity from cartilage (low) to bone (high).

- Microstructural arrangements of collagen fibers.

- Interfacial bonding strength at the tidemark.

Mechanobiology and Cellular Response

Cells at the interface sense mechanical cues through mechanotransduction pathways. Key points:

- Integrins and ion channels as mechanosensors.

- Mechanical loading modulates gene expression in chondrocytes and osteoblasts.

- Excessive or abnormal forces can trigger catabolic pathways leading to matrix degradation.

Pathological Conditions and Clinical Implications

Dysfunction of the bone–cartilage interface contributes to several joint diseases. Identifying early changes at this junction is crucial for timely intervention.

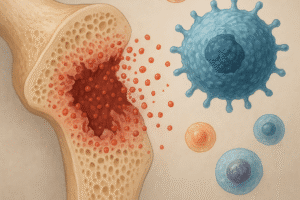

Osteoarthritis (OA)

OA is characterized by:

- Breakdown of articular cartilage and alterations in subchondral bone architecture.

- Formation of osteophytes at joint margins.

- Subchondral bone sclerosis and cyst formation.

Early detection of interface damage through imaging modalities like MRI can guide regenerative therapies before irreversible degeneration.

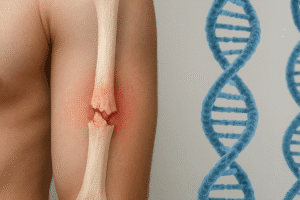

Osteochondral Lesions and Defects

Traumatic injuries can cause focal defects, leading to:

- Loss of cartilage integrity and exposure of subchondral bone.

- Pain, swelling, and impaired joint mechanics.

- Risk of post-traumatic osteoarthritis if untreated.

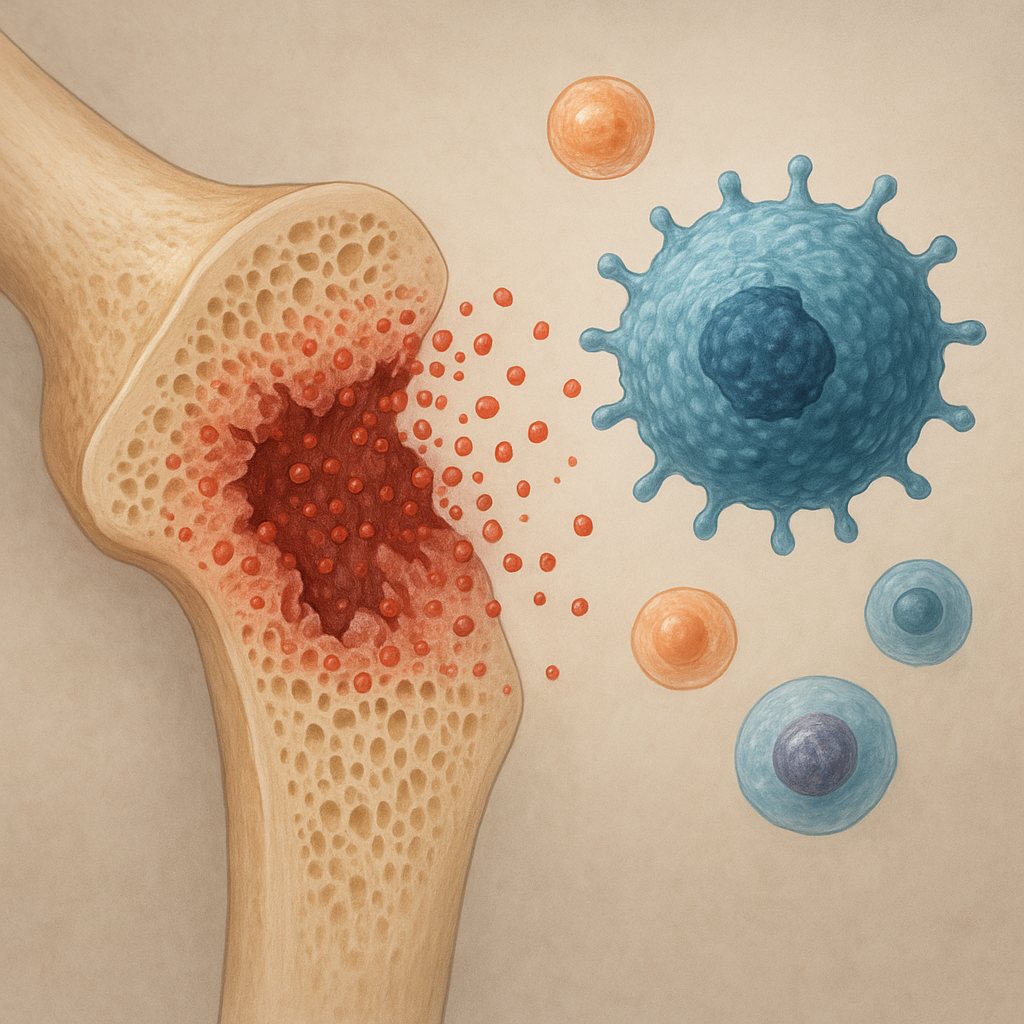

Bone Marrow Lesions and Subchondral Cysts

Magnetic resonance imaging often reveals bone marrow edema and cystic changes below damaged cartilage. Clinical relevance includes:

- Association with pain severity.

- Indicator of ongoing subchondral remodeling.

- Potential target for pharmacological intervention.

Advances in Therapeutic Strategies

Innovations in tissue engineering, biomaterials, and cell-based therapies offer hope for repairing or regenerating the bone–cartilage interface.

Scaffold-Based Approaches

Engineered scaffolds aim to replicate the complex gradient of the osteochondral junction:

- Bi-layer and multi-layer constructs combining cartilage-friendly and bone-friendly biomaterials.

- Use of hydrogels to mimic cartilage hydration.

- Incorporation of bioactive molecules like growth factors for guided tissue formation.

Cell Therapy and Growth Factors

Strategies involve transplanting progenitor cells or delivering signaling molecules to stimulate in situ regeneration:

- Mesenchymal stem cells differentiated into chondrocytes and osteoblasts.

- Controlled release of bone morphogenetic proteins and transforming growth factor-beta.

- Use of extracellular vesicles to modulate local immune and repair responses.

Emerging Technologies

Advanced modalities show promise for personalized and effective repair:

- 3D bioprinting of osteochondral units with precise architecture.

- Nanotechnology-enabled drug delivery across the interface.

- Non-invasive imaging and biomarker development for early assessment of healing.