Bone repair after traumatic injuries involves a multifaceted cascade of cellular activities, mechanical stabilization and clinical interventions. Understanding the intricate processes of inflammation, callus formation and remodeling is essential for optimizing outcomes in patients with fractures. This article explores the biological foundations, surgical strategies and future innovations that shape modern approaches to bone healing.

Biological Mechanisms Underlying Bone Repair

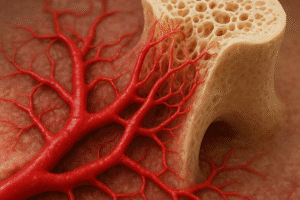

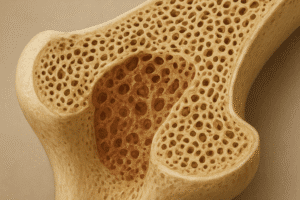

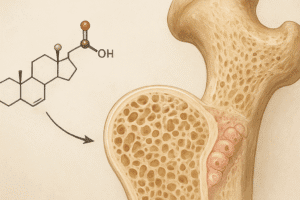

The process of bone healing can be divided into three overlapping phases: the inflammatory phase, the reparative phase and the remodeling phase. Immediately following a fracture, blood vessels rupture, forming a hematoma that serves as a provisional scaffold. Inflammatory cells infiltrate the injury site, releasing cytokines and growth factors that recruit mesenchymal progenitor cells. During the reparative phase, these progenitors differentiate into osteoblasts and chondrocytes, producing a soft cartilaginous callus that stabilizes the fracture. Subsequent vascular invasion—driven by angiogenesis—allows for mineralization of this callus into woven bone. In the remodeling phase, coordinated activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts refines woven bone into mature lamellar bone, restoring the original shape and strength.

Surgical Stabilization Techniques

Effective stabilization of the fracture site is critical to support biological repair and minimize complications. Common techniques include:

- External Fixation: Uses pins or wires connected to external bars, allowing for adjustability and minimal soft-tissue disruption.

- Intramedullary Nailing: A rod inserted into the medullary canal provides load-sharing support, ideal for long-bone fractures.

- Plate Osteosynthesis: Rigid plates and screws offer precise reduction and early mobilization but require extensive exposure.

- Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Fixation: Combines stability with reduced soft-tissue damage.

Choosing the optimal method depends on fracture location, severity, patient comorbidities and the need for early weight-bearing. Stability influences the mechanical environment, which directly affects callus formation and biomechanics of healing.

Role of Biomaterials in Bone Healing

Advances in biomaterials have expanded options for filling bone defects and enhancing repair. Materials fall into three main categories:

- Synthetic Substitutes: Calcium phosphates, bioactive glasses and polymers mimic bone’s mineral phase and degrade over time, facilitating new bone in-growth.

- Natural Grafts: Autografts remain the gold standard due to their osteogenic, osteoinductive and osteoconductive properties but are limited by donor-site morbidity. Allografts offer availability but carry immunogenic risks.

- Composite Constructs: Combining polymers with ceramics or incorporating growth factors enhances mechanical strength and biological activity.

Researchers focus on optimizing porosity, surface chemistry and degradation rates to match physiological requirements. Integration of stem cells with scaffolds in a bioreactor environment shows promise for large defect reconstruction.

Advances in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

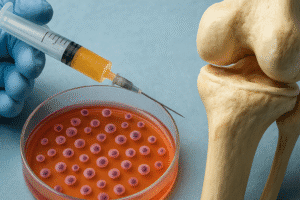

Modern regenerative strategies aim to harness the body’s innate healing potential. Key innovations include:

- Cell-Based Therapies: Harvesting and expanding mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from bone marrow or adipose tissue to deliver high densities of osteoprogenitors.

- Growth Factor Delivery: Controlled release of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) from tailored carriers.

- Gene Therapy: Transduction of cells with osteogenic genes to promote sustained growth factor synthesis at the defect site.

- 3D Bioprinting: Layer-by-layer fabrication of cell-laden constructs with precise architecture to match patient-specific geometries.

Such approaches seek to overcome limitations of traditional grafts, offering solutions for nonunion fractures and critical-size defects. Integration of regenerative medicine with surgical care heralds a new era in personalized bone repair.

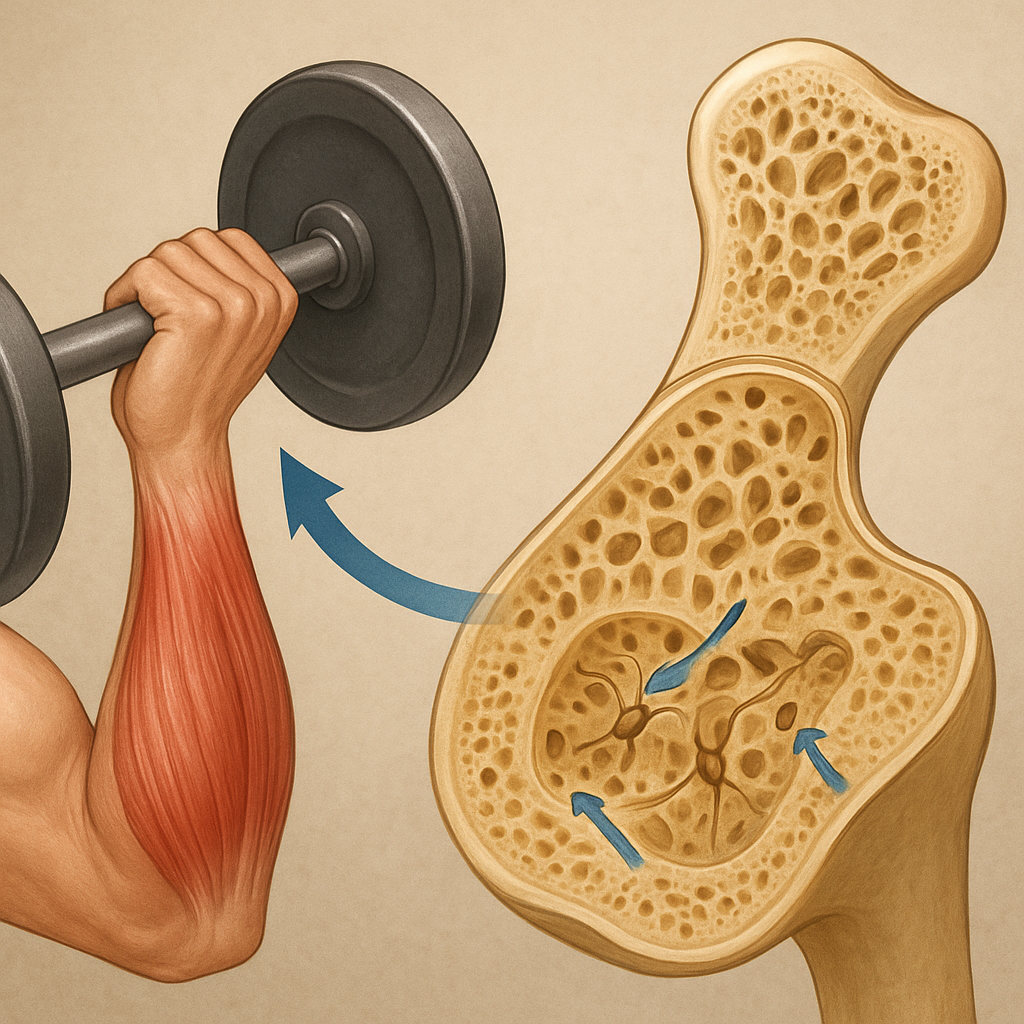

Physical Rehabilitation and Biomechanical Considerations

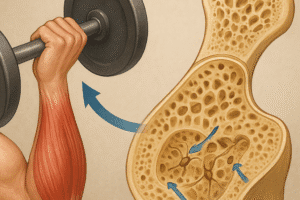

After stabilization, a tailored rehabilitation program is vital to regain function. Early controlled loading stimulates bone formation through mechanotransduction, where cells sense mechanical strain and upregulate osteogenic pathways. Protocols often include:

- Protected Weight-Bearing: Gradual increase in load to stimulate callus maturation without risking displacement.

- Range-of-Motion Exercises: Prevent joint stiffness and maintain soft-tissue health.

- Muscle Strengthening: Preserves surrounding musculature and supports joint integrity.

Monitoring with radiographic imaging and biomechanical assessments guides progression. Failure to adhere to mechanical principles may result in delayed healing or malunion, underscoring the role of rehabilitation specialists in multidisciplinary care.

Complications and Risk Management

Despite optimal strategies, complications can arise. Common issues include:

- Nonunion: Failure to achieve bony union within expected time frames, often due to inadequate stability, poor vascularity or infection.

- Malunion: Healing in a suboptimal position, leading to functional impairment and requiring corrective osteotomy.

- Infection: Particularly in open fractures or when using implants; managed with debridement, antibiotics and possibly implant exchange.

- Soft-Tissue Necrosis: Compromised blood supply can jeopardize healing and necessitate flap coverage.

Identifying risk factors—such as smoking, diabetes, osteoporosis and high-energy trauma—is essential for prevention. Prophylactic measures, including nutritional optimization and meticulous surgical technique, help minimize adverse outcomes.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Ongoing research aims to refine bone repair by integrating digital planning, advanced materials and biologics. Promising areas include:

- Smart Implants: Sensor-enabled devices that monitor strain and deliver real-time feedback for personalized loading protocols.

- Nanotechnology: Surface engineering at the nanoscale to enhance cell adhesion and deliver therapeutic molecules.

- Artificial Intelligence: Predictive analytics to stratify patients by risk and tailor treatment algorithms.

- Autonomous Bioreactors: Intraoperative systems that condition grafts with optimal mechanical and biochemical cues before implantation.

The convergence of engineering, biology and data science holds the potential to revolutionize standard care. Ultimately, the goal is to achieve predictable, rapid and complete restoration of skeletal integrity for all trauma patients.