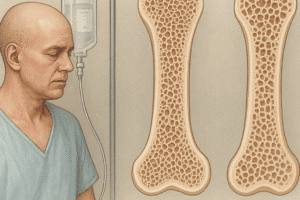

Bone Mineral Density (BMD) tests play a pivotal role in the assessment of skeletal health, offering clinicians and patients valuable insights into the strength and integrity of bones. By quantifying the concentration of minerals within bone tissue, these diagnostic tools help identify individuals at risk of **osteoporosis** and related **fractures**, guide therapeutic decisions, and monitor the effectiveness of treatment regimens. The following sections explore the fundamental concepts, methodologies, clinical implications, and future directions of BMD testing in modern medicine.

What Is Bone Mineral Density?

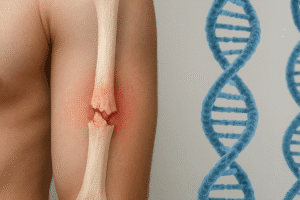

Bone Mineral Density refers to the amount of mineral matter per square centimeter of bones. It is an indirect measure of bone strength and structural integrity. While genetic factors establish an individual’s baseline BMD, lifestyle and environmental influences, such as diet, physical activity, and hormonal status, continuously modify bone mass throughout life.

Definition and Significance

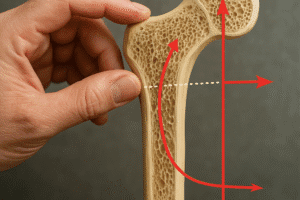

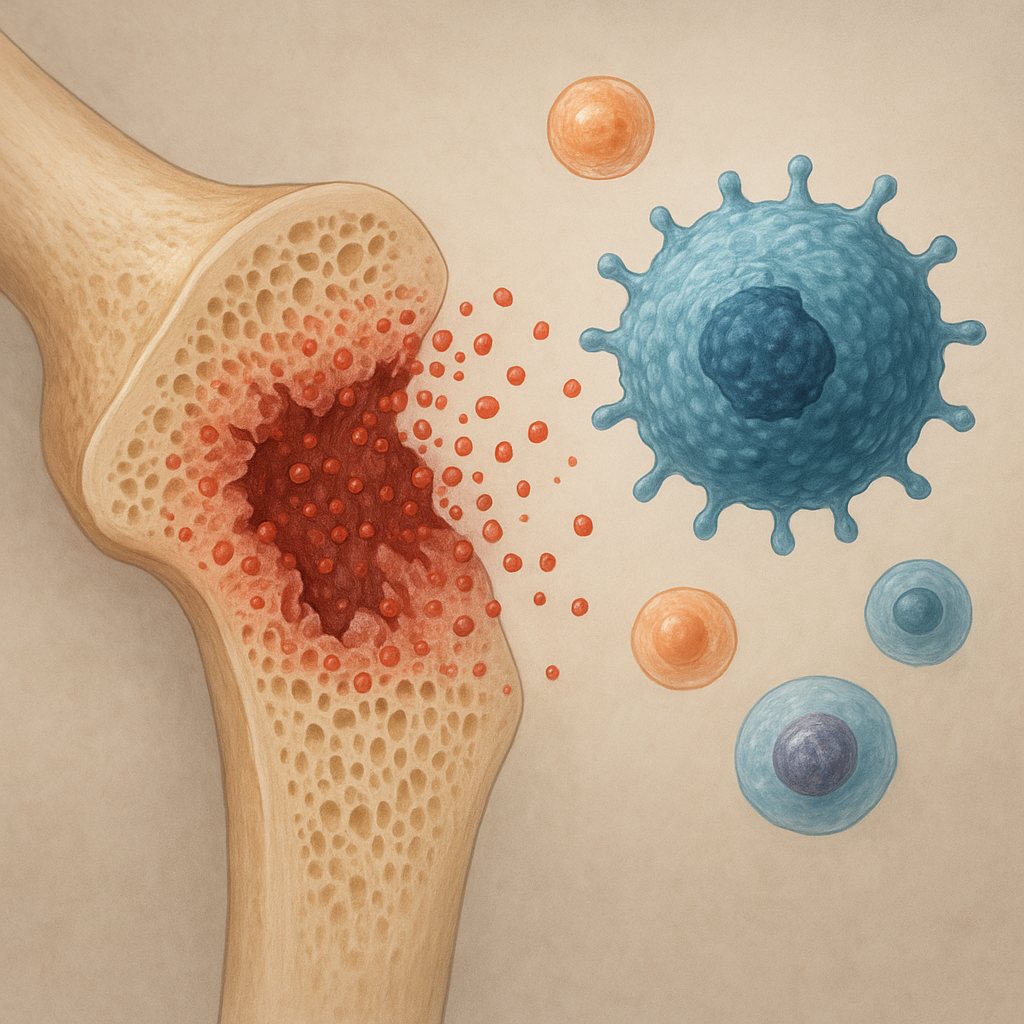

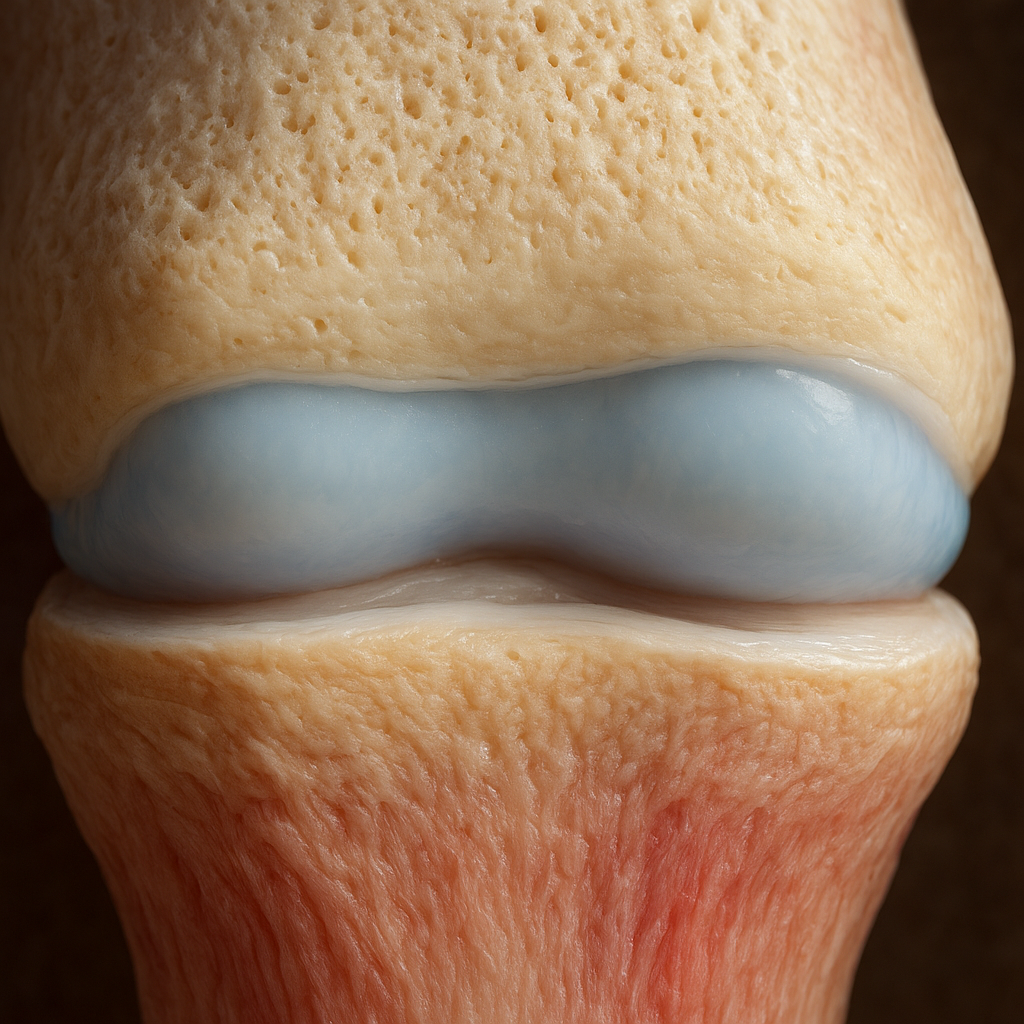

At the microscopic level, bones consist of a matrix of collagen fibers reinforced by crystalline hydroxyapatite, primarily composed of **calcium** and phosphate. BMD tests evaluate the density of these crystals, serving as an indicator of bone quality. Low BMD values often correlate with increased bone fragility and a higher likelihood of fractures following minimal trauma. Conversely, higher BMD values suggest more robust bone architecture and a reduced risk of injury.

Types of Bone Mineral Density Tests

A variety of imaging technologies have been developed to measure BMD. Each method offers unique advantages and limitations regarding precision, accessibility, cost, and radiation exposure.

- dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA): Regarded as the gold standard for BMD assessment, DEXA uses two X-ray beams at different energy levels to differentiate between bone and soft tissue. It provides precise measurements at critical skeletal sites like the hip and spine.

- Quantitative CT: This technique employs computed tomography to produce cross-sectional images, enabling three-dimensional evaluation of bone density. It is particularly useful for assessing trabecular bone but involves higher radiation doses compared to DEXA.

- Quantitative Ultrasound (QUS): Utilizing sound waves, QUS estimates bone stiffness and density, commonly at peripheral sites such as the heel. While radiation-free and portable, its results are less standardized than those of DEXA or CT.

Indications and Preparation

BMD testing is recommended for individuals at heightened risk of bone loss or fractures. Typical indications include:

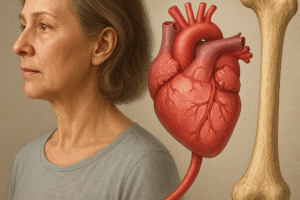

- Postmenopausal women aged 65 and older

- Men aged 70 and older

- Adults with risk factors such as long-term glucocorticoid therapy, early menopause, or a history of fractures

- Patients with conditions affecting bone metabolism (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, hypogonadism)

To ensure accurate results, patients are generally advised to:

- Avoid calcium supplements for at least 24 hours prior to the test

- Inform the technician of any recent imaging studies involving contrast agents

- Wear loose, metal-free clothing during measurement

Interpreting Bone Mineral Density Results

Results from BMD tests are expressed primarily through two standardized scores: the T-score and the Z-score.

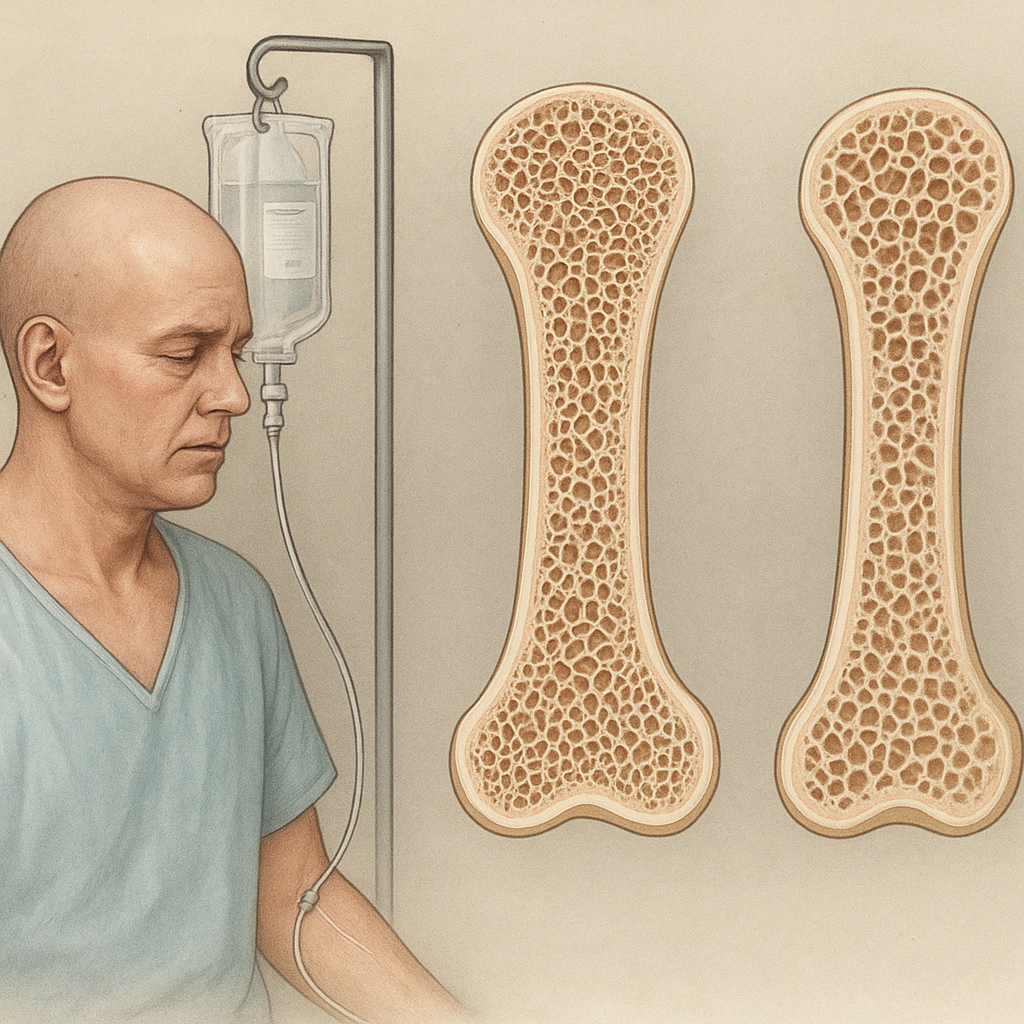

- T-score: Compares a patient’s BMD to the average peak BMD of a healthy, young adult reference population. A T-score of -1.0 or above is considered normal, between -1.0 and -2.5 indicates osteopenia, and -2.5 or lower confirms **osteoporosis**.

- Z-score: Compares BMD to age-, sex-, and ethnicity-matched norms. Z-scores below -2.0 suggest that factors other than aging may be contributing to bone loss, warranting further investigation.

Clinicians also evaluate the patient’s overall fracture risk using tools like the FRAX® algorithm, which integrates BMD values with clinical risk factors such as smoking status, alcohol intake, and family history.

Factors Influencing Bone Density

Understanding the variables that affect bone health is essential for prevention and management strategies:

- Nutrition: Adequate intake of **calcium** and **Vitamin D** supports mineralization. Diets lacking these nutrients, or malabsorption syndromes, can precipitate bone loss.

- Physical Activity: Weight-bearing and resistance exercises stimulate bone formation by enhancing mechanical loading.

- Endocrine Factors: Hormones such as estrogen, testosterone, and parathyroid hormone regulate bone remodeling. Menopause-related estrogen deficiency accelerates bone resorption.

- Medications: Long-term glucocorticoid therapy and certain anticonvulsants can decrease BMD.

- Lifestyle: Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption interfere with bone turnover and repair mechanisms.

Risks and Limitations of BMD Testing

While BMD assessments are invaluable, they present certain constraints:

- Radiation Exposure: Although minimal with DEXA, cumulative exposure should be monitored, especially in younger patients.

- Site Specificity: Measurements focus on hip, spine, or peripheral sites and may not reflect bone density in other regions.

- Artifact Susceptibility: Vascular calcifications, degenerative changes, or surgical implants can falsely elevate BMD readings.

- Inter-machine Variability: Differences in calibration and software algorithms can affect comparability across centers, underscoring the need for standardized protocols.

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Advancements in imaging, data analysis, and biomarker research are refining the assessment of bone quality beyond mere density. Ongoing innovations include:

- High-resolution peripheral quantitative CT (HR-pQCT), capable of visualizing microarchitecture and enabling volumetric analysis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques that characterize bone marrow composition and trabecular network connectivity without ionizing radiation.

- Artificial intelligence and machine-learning algorithms that integrate clinical, imaging, and biochemical data to improve risk prediction and personalize treatment strategies.

As these modalities mature, they promise to enhance the precision of fracture risk estimation, optimize the timing of interventions, and broaden our understanding of skeletal fragility.

Conclusion

Bone Mineral Density tests remain the cornerstone of osteoporosis diagnosis and fracture risk assessment. By combining standardized imaging techniques, clinical evaluation, and emerging analytic tools, healthcare providers can deliver targeted preventive measures and therapies, ultimately preserving skeletal health and quality of life for at-risk populations.