The growing demand for bone grafts in orthopedic and dental procedures has spurred research into biomaterials that can support and enhance osteogenesis. This article explores two major categories: synthetic and natural bone grafts. By comparing porosity, vascularization, and overall integration, clinicians and researchers can optimize patient outcomes and guide future innovations.

The Biological Basis of Bone Grafts

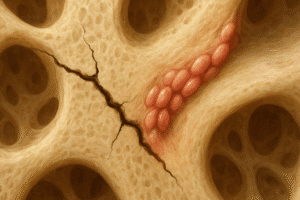

Bone grafting aims to restore skeletal integrity by promoting regeneration of osseous tissue. Key processes include:

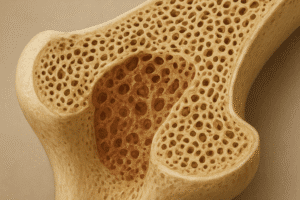

- Osteoconduction: Graft acts as a scaffold for new bone growth.

- Osteoinduction: Recruitment and differentiation of progenitor cells.

- Osteogenesis: Direct contribution of living cells to new bone formation.

A successful graft must exhibit biocompatibility, structural stability, and the ability to integrate seamlessly with host tissue. Factors such as mechanical strength, degradation rate, and immune response determine clinical performance.

Synthetic Grafts: Materials and Mechanisms

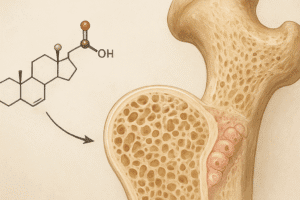

Synthetic grafts derive from engineered compounds designed to mimic natural bone matrix. Common materials include:

- Calcium phosphates (e.g., hydroxyapatite, tricalcium phosphate)

- Bioactive glasses

- Polymeric composites (e.g., polylactic acid, polyglycolic acid)

These biomaterials offer several advantages:

- Unlimited supply without donor site morbidity

- Consistent quality and physicochemical properties

- Tailorable porosity and degradation kinetics

However, challenges include:

- Potential for inflammatory response due to particulate byproducts

- Limited intrinsic growth factors—often requiring coating or impregnation with biological agents

- Variable mechanical match to host bone, particularly in load-bearing applications

Natural Grafts: Autografts, Allografts, Xenografts

Natural grafts originate from living tissue sources and inherently contain cellular and molecular signals:

- Autografts: Patient’s own bone (e.g., iliac crest)

- Allografts: Donor human bone processed to remove antigenic components

- Xenografts: Animal-derived matrices, typically bovine or porcine

Key benefits include:

- Rich supply of native growth factors

- Excellent osteoinductive potential

- Intimate contact with host bone under favorable conditions

Limitations involve:

- Donor site morbidity (autograft)

- Risk of disease transmission or immune reaction (allograft, xenograft)

- Unpredictable resorption rates, potential for incomplete remodeling

Comparison of Key Parameters

When evaluating synthetic versus natural grafts, several criteria guide material selection:

Mechanical Properties

- Synthetic ceramics can be tailored for compressive strength but may lack tensile resilience.

- Natural autografts closely match host bone biomechanics but require additional surgery.

Biological Performance

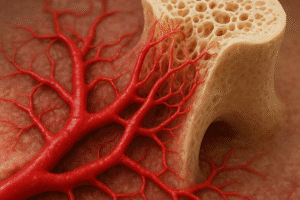

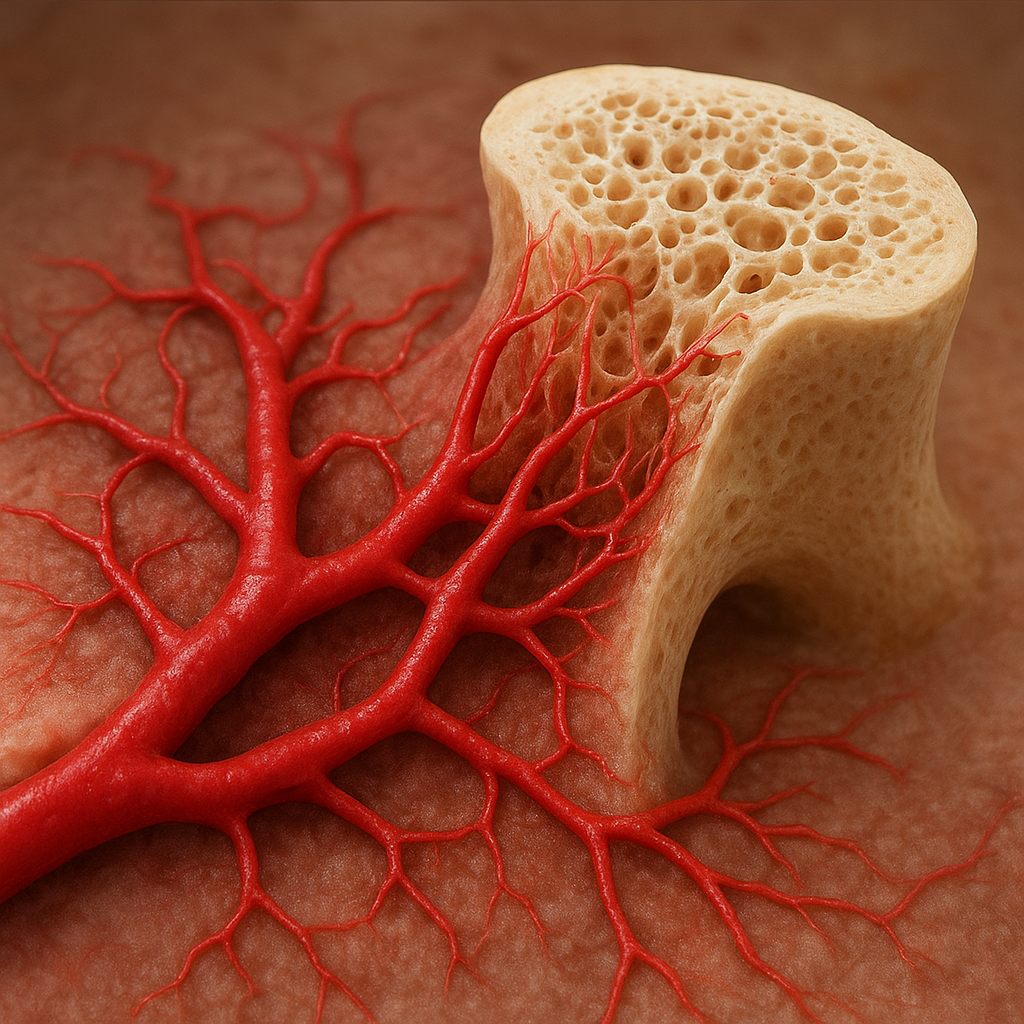

- Autografts provide living cells and proteins essential for rapid vascularization.

- Allografts and xenografts undergo processing that can reduce bioactivity.

- Synthetic matrices often need functionalization with peptides or growth factors to enhance integration.

Resorption and Remodeling

- Ideal graft material degrades at a rate commensurate with new bone formation.

- Synthetic polymers may degrade too quickly, compromising structural support.

- Ceramic-based grafts degrade slowly, which can delay complete remodeling.

Clinical Applications and Future Directions

Choice of graft depends on the defect size, location, and patient-specific factors. Common scenarios include:

- Spinal fusion: Preference for structural grafts with high compressive strength.

- Dental implants: Requirement for rapid osseointegration and stable peri-implant bone levels.

- Trauma reconstruction: Need for customizable shapes and quick restoration of load-bearing capacity.

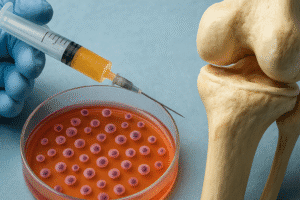

Emerging technologies aim to bridge the gap between synthetic consistency and natural bioactivity. Strategies involve:

- 3D-printed scaffolds loaded with stem cells or growth factors

- Smart materials responsive to physiological cues (pH, enzymes)

- Composite systems combining ceramics, polymers, and biologics

Continuous advancements in material science and tissue engineering promise grafts that not only replace missing bone but also actively direct healing toward full functional recovery.