The integrity of the human skeleton depends on the intricate interplay between mineral crystals and protein fibers. Among these components, collagen holds a central role in providing flexibility, resilience, and a template for mineral deposition. This article explores the multifaceted contributions of collagen to bone physiology, examines the molecular mechanisms that govern its function, and highlights emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at harnessing collagen’s potential in bone repair and regeneration.

Composition and Architecture of Bone Matrix

The bone matrix is a complex composite material comprising an organic fraction and an inorganic mineral phase. The organic compartment, largely responsible for the material’s toughness, consists predominantly of collagen type I fibers interspersed with noncollagenous proteins. In contrast, the inorganic portion is mainly formed by hydroxyapatite crystals that impart stiffness and load-bearing capacity.

At the microscopic level, collagen molecules assemble into fibrils with a characteristic 67-nanometer banding pattern. These fibrils further bundle into fibers that serve as a scaffold for mineral nucleation. This hierarchical arrangement endows bone with high tensile strength while maintaining sufficient elasticity to absorb mechanical shocks.

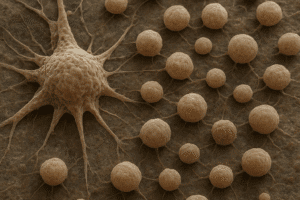

Bone remodeling—a dynamic process involving resorption and formation—relies heavily on the quality of this composite. Specialized cells, such as osteoclasts and osteoblasts, coordinate to remove old bone and deposit new matrix, respectively. Osteoblasts secrete type I collagen and orchestrate the local environment to favor mineralization, whereas osteoclasts secrete enzymes and acids that degrade both collagen and mineral, allowing for renewal and adaptation to changing mechanical demands.

Types of Collagen and Their Functional Significance

Although over 28 collagen types exist in vertebrates, types I, III, and V are most relevant to bone tissue. Type I constitutes over 90% of the organic matrix, forming thick, robust fibers. Type III collagen often co-polymerizes with type I, modulating fibril diameter and organization, while type V contributes to fibril nucleation and regulates overall fiber architecture.

- Type I Collagen: The principal structural protein, providing the majority of bone’s mechanical strength.

- Type III Collagen: Influences fibril size and elasticity; commonly found near vascular channels and remodeling sites.

- Type V Collagen: Acts as a nucleator for fibrillogenesis, ensuring proper assembly and alignment of type I fibers.

Post-translational modifications, such as hydroxylation of proline and lysine residues, are essential for triple-helix stability. Enzymatic cross-links formed by lysyl oxidase further stabilize the fibrillar network, contributing significantly to bone’s overall rigidity and energy-dissipating capacity.

Collagen Cross-linking and Mechanical Properties

Cross-linking between collagen molecules is a critical determinant of bone quality. Two primary types of cross-links exist: enzymatic and nonenzymatic. Enzymatic cross-links, mediated by lysyl oxidase, create stable bonds that enhance tensile strength and resistance to deformation. In contrast, advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) lead to nonenzymatic cross-links that can stiffen collagen excessively, reducing its ability to withstand impact and increasing fracture risk.

Mechanical testing has demonstrated that bones with optimal cross-link profiles exhibit improved toughness and durability. Insufficient cross-linking can lead to brittle bones, whereas excessive nonenzymatic cross-links are hallmarks of aging and diabetic bone fragility.

Role of Water and Mineral in Collagen Mechanics

Water molecules bound to collagen fibrils contribute to viscoelastic behavior, allowing energy dissipation under cyclic loading. Similarly, the intimate association of hydroxyapatite with collagen fibers creates a synergistic composite: the mineral phase resists compressive forces, while the organic matrix resists tension.

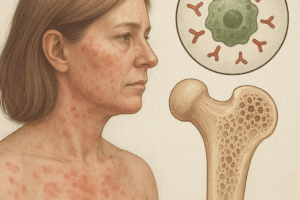

Clinical Implications: Osteoporosis and Tissue Engineering

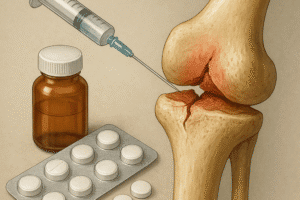

Age-related decline in collagen quality is a major factor in osteoporosis, a condition characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration. Decreased enzymatic cross-linking, accumulation of AGEs, and altered expression of collagen-modifying enzymes all contribute to compromised bone strength.

Current therapeutic approaches aim not only to inhibit bone resorption but also to enhance collagen integrity. Selective inhibition of cathepsin K, a protease secreted by osteoclasts, has shown promise in preserving collagen scaffolding. Additionally, nutritional interventions rich in vitamin C and copper support collagen hydroxylation and cross-linking.

Advances in Collagen-Based Biomaterials

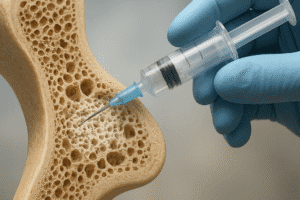

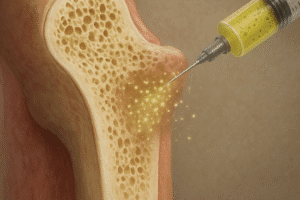

In regenerative medicine, tissue engineering leverages collagen’s inherent bioactivity to develop scaffolds for bone repair. Electrospun collagen nanofibers, mineralized collagen matrices, and collagen–hydroxyapatite composites mimic the native bone environment, promoting cell adhesion and osteogenic differentiation.

- Collagen sponges loaded with growth factors accelerate healing in critical-size defects.

- Three-dimensional printed collagen–ceramic hybrids enable patient-specific scaffold fabrication.

- Genetically engineered collagen variants with enhanced cross-linking sites show improved mechanical performance.

Future Directions in Collagen Research

Emerging studies focus on the molecular pathways that regulate collagen synthesis and degradation. Gene editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9 offer the potential to correct mutations in collagen-encoding genes responsible for heritable bone diseases such as osteogenesis imperfecta. Meanwhile, novel imaging techniques that visualize collagen orientation and cross-link distribution in vivo are shedding light on how microstructural changes translate to macroscopic bone strength.

Combining insights from molecular biology, materials science, and biomechanics will allow the design of next-generation therapies targeting both mineral and organic phases. By tailoring collagen’s structural and biochemical properties, researchers aim to create adaptable, resilient bone substitutes that restore function in patients suffering from trauma, disease, or congenital defects.