The intricate balance between skeletal integrity and physiological processes is profoundly influenced by the passage of time. As individuals transition through various life stages, the structural and functional attributes of bone tissue undergo significant alterations. Understanding the multifaceted relationship between aging and fracture risk is essential for clinicians, researchers, and public health professionals aiming to develop effective prevention and management strategies. This article explores age-related changes in bone, identifies key contributors to skeletal vulnerability, and highlights current and emerging interventions designed to preserve bone health throughout the lifespan.

Age-Related Changes in Bone Structure and Function

Cellular Mechanisms Underlying Bone Remodeling

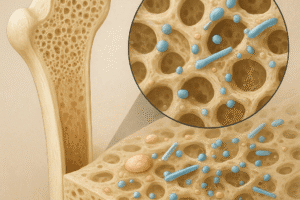

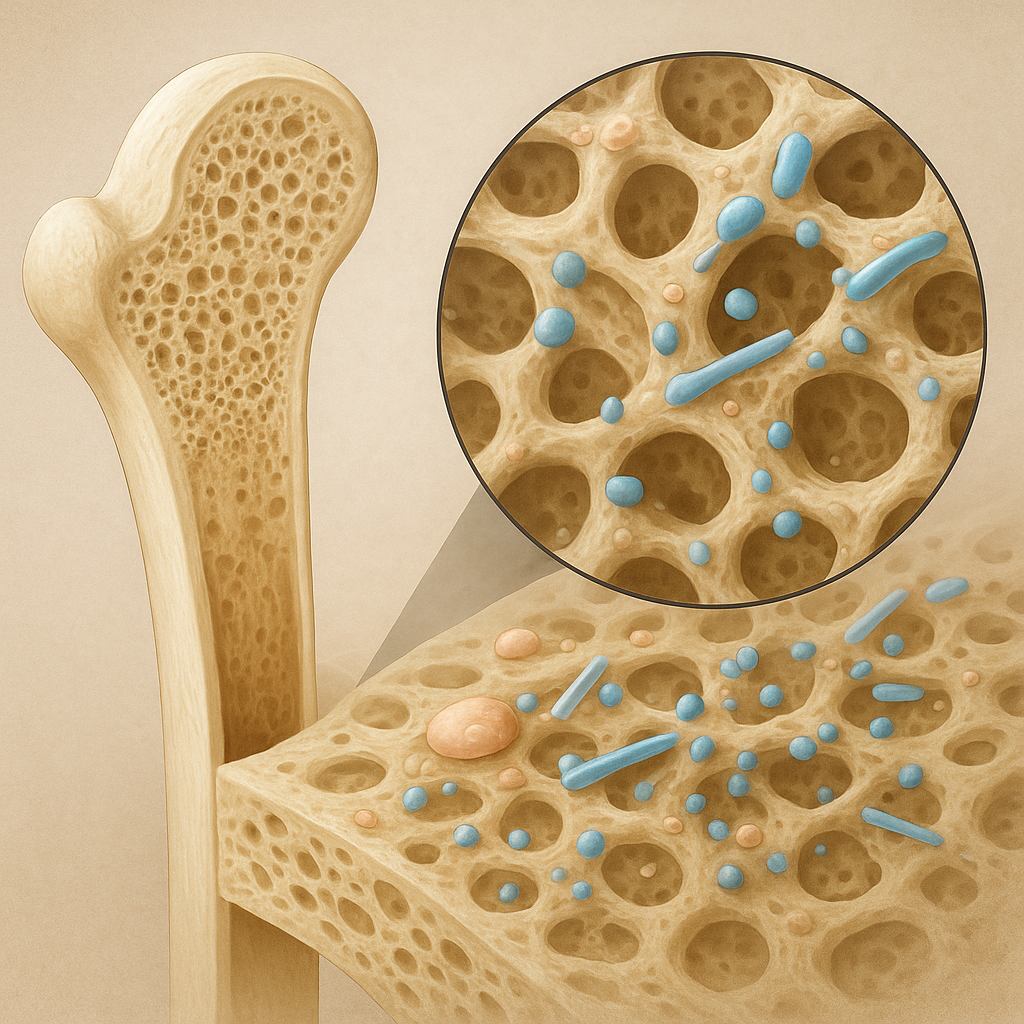

Bone is a living organ characterized by a continuous cycle of resorption and formation. Osteoclasts, derived from hematopoietic lineage, degrade mineralized matrix, while osteoblasts, originating from mesenchymal stem cells, deposit new collagenous scaffolds that later mineralize. In youth, these processes remain balanced, maintaining optimal bone mineral density (BMD). However, with advancing age, several cellular shifts occur:

- Decreased osteoblast proliferation and activity

- Prolonged osteoclast lifespan and increased resorptive capacity

- Impaired differentiation of progenitor cells

- Elevated apoptosis of bone-forming cells

The net effect is an imbalance favoring resorption, leading to cortical thinning and trabecular thinning, hallmarks of age-associated skeletal fragility.

Microarchitectural Alterations

Beyond quantitative BMD loss, microstructural deterioration plays a pivotal role in fracture susceptibility. Key changes include:

- Trabecular perforation and loss of connectivity

- Increased cortical porosity

- Altered collagen cross-linking, reducing bone toughness

Together, these alterations compromise the mechanical properties of bone, making it more prone to cracks that can propagate under minimal stress.

Contributing Factors to Increased Fracture Risk in Older Adults

Endocrine and Metabolic Influences

Hormonal shifts dramatically affect skeletal homeostasis. In postmenopausal women, the abrupt decline in estrogen accelerates bone resorption. In men, gradual testosterone reduction contributes to BMD loss, although at a slower pace. Other endocrine factors include:

- Thyroid hormone excess, which stimulates osteoclastic activity

- Hyperparathyroidism, leading to elevated bone turnover

- Insulin-like growth factors, whose decline impairs osteoblast function

Nutritional Deficiencies

Optimal bone health depends on sufficient intake and absorption of critical nutrients. Common deficiencies in older populations are:

- Calcium insufficiency, impairing mineral deposition

- Vitamin D deficiency, reducing intestinal calcium uptake and negatively affecting muscle strength

- Protein-energy malnutrition, limiting matrix synthesis

Comorbidities and Medications

Several age-related conditions and their treatments can elevate fracture risk:

- Sarcopenia, characterized by muscle mass and strength decline, increases the likelihood of falls.

- Chronic inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) promote systemic bone loss.

- Glucocorticoid therapy, which induces rapid osteoblast apoptosis and inhibits bone formation.

- Proton pump inhibitors, potentially affecting calcium absorption.

Environmental and Lifestyle Contributors

Factors that predispose older adults to falls and fractures include:

- Poor balance and gait instability

- Unsafe home environments with tripping hazards

- Visual impairment and diminished proprioception

- Physical inactivity leading to functional decline

Strategies for Prevention and Management of Fracture Risk

Screening and Risk Assessment

Early identification of individuals at high risk enables timely intervention. Key tools include:

- BMD measurement via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

- Fracture risk algorithms (e.g., FRAX) incorporating clinical risk factors

- Vertebral imaging to detect asymptomatic fractures

Nutrition and Supplementation

Ensuring adequate intake of bone-supportive nutrients is foundational:

- Calcium: 1,000–1,200 mg daily through diet or supplements

- Vitamin D: 800–1,000 IU daily to maintain serum 25(OH)D > 30 ng/mL

- Protein: at least 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day to support matrix synthesis

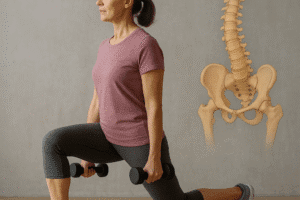

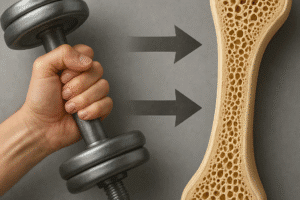

Physical Activity and Fall Prevention

Exercise programs tailored to older adults can enhance strength, balance, and coordination:

- Weight-bearing activities (e.g., walking, light jogging)

- Resistance training to stimulate bone formation

- Balance exercises (e.g., Tai Chi, single-leg stands)

Home modification, vision correction, and medication review can further reduce fall incidence.

Pharmacological Interventions

Multiple drug classes are approved for osteoporosis and fracture prevention:

- Bisphosphonates: inhibit osteoclast-mediated resorption

- Denosumab: monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): preserve bone density with tissue-specific estrogenic effects

- Parathyroid hormone analogs (e.g., teriparatide): stimulate osteoblast activity

- Romosozumab: sclerostin inhibitor with dual anabolic and antiresorptive effects

Emerging Research and Future Directions

Biomarkers and Imaging Advances

Novel biochemical markers of bone turnover and high-resolution imaging techniques (e.g., HR-pQCT) are poised to enhance individualized risk stratification by capturing microarchitectural changes before overt BMD loss occurs.

Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Engineering

Stem cell–based therapies and bioactive scaffolds aim to restore damaged bone. Early-phase clinical trials are evaluating mesenchymal stem cell transplantation to promote osseous regeneration after large defects or severe osteoporosis.

Personalized Medicine and Genomics

Genetic profiling may uncover polymorphisms linked to accelerated bone loss, enabling targeted prophylactic approaches. Integration of genomic data with lifestyle and clinical factors holds promise for precision bone health strategies.