Bone regeneration requires a finely tuned sequence of cellular and molecular events. Cigarette smoking disrupts this process at multiple levels, leading to delayed union, nonunion, and increased risk of complications. This article examines the underlying mechanisms by which tobacco use impairs skeletal repair, reviews clinical data on patient outcomes, and explores strategies to optimize recovery in smokers.

Biological Mechanisms Affected by Tobacco Exposure

The process of bone healing can be divided into three overlapping phases: the inflammatory response, the reparative stage, and remodeling. Tobacco smoke contains thousands of chemicals, among them nicotine, carbon monoxide, and various free radicals. These agents collectively induce high levels of oxidative stress, reduce oxygen delivery, and interfere with cellular function. In particular, osteoprogenitor cells and osteoblasts suffer impaired proliferation and differentiation.

Inflammatory Response

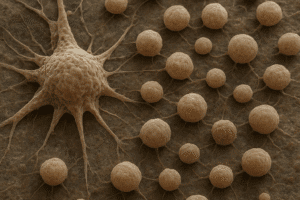

The initial stage of bone repair relies on a controlled burst of inflammation. Macrophages and neutrophils clear debris and secrete cytokines that recruit mesenchymal stem cells. Cigarette smoke skews cytokine profiles, leading to excessive or prolonged inflammation. This dysregulation can damage healthy tissue near the injury site and delay progression to subsequent phases.

Reparative Stage and Angiogenesis

During this phase, a soft callus forms and new blood vessels invade the injury site to support angiogenesis. Adequate vascularity is essential for nutrient delivery and waste removal. Elevated levels of carbon monoxide reduce oxygen saturation, while nicotine induces vasoconstriction, limiting vessel growth. These factors collectively hamper the formation of a robust bony matrix.

Remodeling Phase

In the final phase, woven bone is gradually replaced by lamellar bone, restoring mechanical strength. Tobacco-related toxins impair osteoclastic resorption and subsequent osteoblastic deposition, leading to inferior bone quality. Over time, repeated episodes of smoking can predispose individuals to osteoporosis and further compromise skeletal integrity.

Clinical Evidence and Patient Outcomes

Numerous studies have demonstrated that smokers experience higher rates of delayed union and nonunion following fractures or orthopedic surgery. A meta-analysis of spinal fusion procedures revealed that smokers had a nonunion rate up to three times higher than nonsmokers. Similarly, the risk of postoperative infection and hardware failure increases substantially in patients who continue tobacco use.

- Delayed healing of long bone fracture sites

- Higher incidence of surgical site infection

- Reduced bone mineral density over time

- Increased need for revision surgery

Beyond acute fracture care, chronic smokers face greater challenges in recovering from joint replacements and spinal fusions. Reduced bone-to-implant contact and compromised osseointegration are common findings. These issues translate to longer hospital stays, elevated healthcare costs, and diminished patient satisfaction.

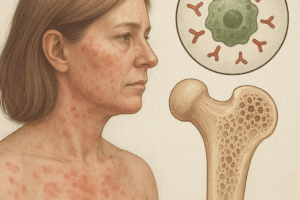

Risk Modifiers and Patient Characteristics

Not all smokers exhibit the same degree of impairment in bone healing. Factors such as the number of cigarettes per day, duration of tobacco use, and presence of comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, peripheral vascular disease) can modulate risk. Passive exposure to secondhand smoke may also exert deleterious effects, especially in pediatric populations with open growth plates.

Age and Hormonal Status

Advancing age intrinsically slows reparative processes. When combined with smoking, older individuals show markedly reduced callus formation. In women, the menopausal decline in estrogen further amplifies susceptibility to bone loss and compromises repair capacity.

Nutritional Deficiencies

Smokers often have lower levels of vitamin D, calcium, and protein intake—nutrients critical for bone matrix synthesis. Malnutrition intensifies the negative impact of tobacco-related toxins on cellular function and structural integrity.

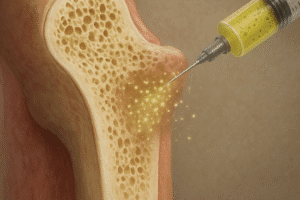

Strategies to Mitigate Smoking-Related Risks

Given the substantial impact of tobacco on skeletal repair, perioperative management should incorporate dedicated smoking cessation interventions. Preoperative abstinence of at least four weeks has been linked to improved surgical outcomes and faster union rates.

- Smoking cessation counseling and support groups

- Nicotine replacement therapy under medical supervision

- Pharmacotherapy with varenicline or bupropion to reduce cravings

- Optimizing nutritional status with supplements of vitamin D and calcium

Adjunctive Therapies

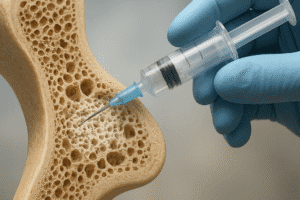

Emerging modalities such as low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and extracorporeal shockwave therapy show promise in enhancing callus formation even in smokers. Bone stimulators may partially counteract the inhibitory effects of tobacco on cell proliferation.

Postoperative Monitoring

Close radiographic follow-up is crucial for early detection of delayed union. Surgeons may consider bone grafting or use of synthetic osteoinductive materials in high-risk patients. Multidisciplinary collaboration with endocrinologists and nutritionists can further optimize the biological environment for repair.

Conclusion of Key Points

Smoking exerts a multifaceted negative impact on bone regeneration, from the molecular level to clinical outcomes. By understanding these mechanisms and implementing targeted interventions—such as smoking cessation, nutritional optimization, and adjunctive bone stimulation—healthcare providers can significantly improve fracture healing and surgical success rates in this vulnerable population.