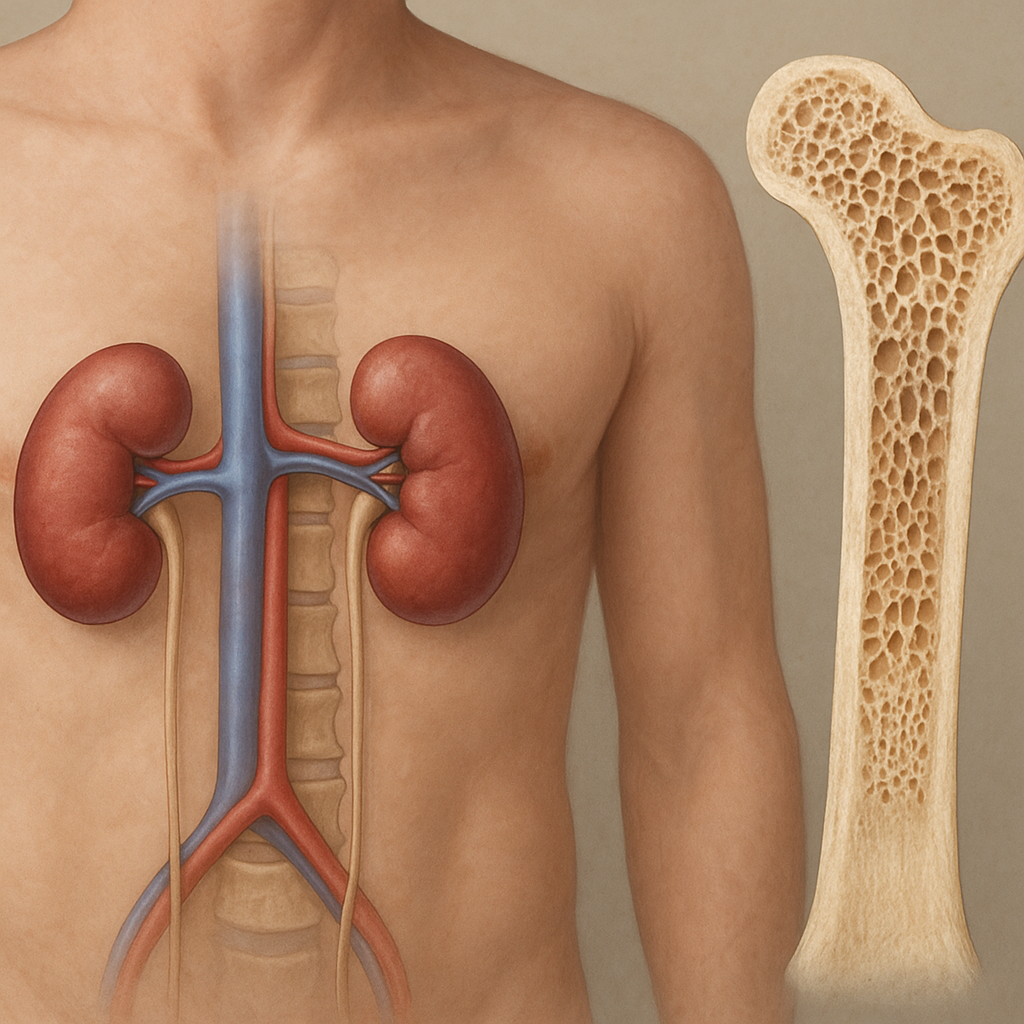

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) exerts profound effects on the skeletal system, leading to a spectrum of metabolic bone disorders. Patients with impaired renal function face disturbances in mineral homeostasis, altered hormone levels, and changes in bone turnover that collectively increase the risk of fractures and reduce quality of life. Understanding the complex interplay between kidney dysfunction and bone health is essential for clinicians, researchers, and patients aiming to mitigate these complications.

Impact on Mineral Metabolism and Hormonal Regulation

The kidneys play a pivotal role in maintaining phosphate balance and activating vitamin D. As glomerular filtration rate declines, phosphate retention leads to hyperphosphatemia. Elevated serum phosphate stimulates the release of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) from osteocytes, which in turn suppresses renal 1-alpha-hydroxylase activity, reducing the conversion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Lower levels of active vitamin D diminish intestinal calcium absorption, resulting in hypocalcemia and subsequent stimulation of parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion – a condition known as secondary hyperparathyroidism.

The interplay between PTH and bone is central to CKD-related bone disease. Persistently elevated PTH increases bone turnover, leading to subtypes of renal osteodystrophy such as osteitis fibrosa cystica. Conversely, oversuppression of PTH, often through aggressive vitamin D analog therapy or calcimimetics, can result in adynamic bone disease characterized by low bone turnover and impaired bone formation. Both high-turnover and low-turnover bone disorders compromise skeletal integrity and predispose patients to fractures.

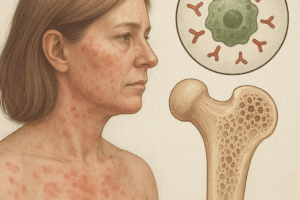

Clinical Manifestations and Risk Factors

CKD-related bone disorders frequently remain subclinical until a fracture or significant bone pain occurs. Common clinical features include diffuse bone pain, muscle weakness, and deformities. Fracture sites often involve the hip, spine, and forearm, significantly impacting mobility and independence.

- Duration of kidney disease: Longer CKD duration correlates with more severe mineral and bone abnormalities.

- Dialysis status: Patients on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis exhibit more pronounced disturbances in mineral metabolism compared to those in earlier CKD stages.

- Age, gender, and ethnicity: Older patients and postmenopausal women are at higher fracture risk, while certain ethnic groups show variability in bone mineral density.

- Comorbidities: Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease exacerbate bone fragility through inflammatory pathways and vascular calcification.

Early recognition of these risk factors enables timely intervention to prevent irreversible skeletal damage.

Diagnostic Approaches and Biomarkers

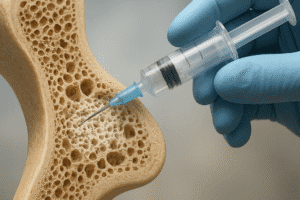

Accurate diagnosis of CKD-related bone disorders relies on a combination of biochemical tests, imaging, and, in select cases, bone biopsy. Standard laboratory assessments include serum levels of calcium, phosphate, PTH, alkaline phosphatase, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Measurement of FGF23 is increasingly utilized to evaluate phosphate metabolism and predict cardiovascular risk.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) remains the cornerstone for assessing bone mineral density (BMD), although it does not differentiate between the various forms of renal osteodystrophy. High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) offers insights into bone microarchitecture but is limited by cost and availability. In ambiguous cases, a transiliac bone biopsy with tetracycline labeling provides definitive information on bone turnover, mineralization, and volume.

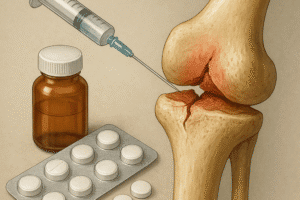

Management and Therapeutic Strategies

Effective management of CKD-related bone disease demands a multifaceted approach aimed at correcting mineral imbalances, controlling PTH, and preserving bone strength. Key strategies include:

- Dietary phosphate restriction: Limiting dietary phosphate and using phosphate binders reduces hyperphosphatemia. Choices of binders (calcium-based vs. non–calcium-based) should consider calcium load and vascular calcification risk.

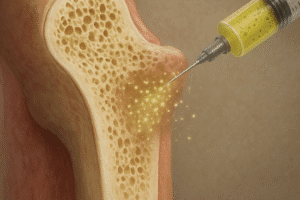

- Vitamin D supplementation: Active vitamin D analogs (e.g., calcitriol) or nutritional vitamin D replenishment corrects deficiency, lowers PTH, and improves bone health.

- Calcimimetics: Agents such as cinacalcet enhance the sensitivity of the calcium-sensing receptor, effectively reducing PTH secretion without elevating serum calcium or phosphate.

- Individualized dialysis prescriptions: Optimizing dialysis dose and modality can aid in phosphate removal and acid-base balance, indirectly benefiting bone turnover.

- Emerging therapies: Research into novel agents targeting FGF23 signaling, sclerostin inhibitors, and anabolic treatments holds promise for future management.

Close monitoring of biochemical parameters and periodic BMD assessments guide therapy adjustments to achieve optimal bone health outcomes.

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Despite advances in understanding CKD-related bone disease, many questions remain. Investigational areas include:

- Role of genetic polymorphisms in PTH receptor and vitamin D receptor affecting individual response to therapy.

- Long-term effects of novel phosphate-binding polymers and selective FGF23 inhibitors on cardiovascular morbidity.

- Integration of artificial intelligence in predicting fracture risk and customizing treatment protocols.

- Impact of exercise regimens and nutritional interventions on bone quality in CKD populations.

Collaborative efforts between nephrologists, endocrinologists, and orthopedic specialists are essential to develop personalized strategies that address both kidney function and skeletal integrity. Continued research will pave the way for innovative therapies aiming to minimize fractures, enhance patient well-being, and reduce healthcare burden associated with CKD-related bone disease.