Cancer treatment has advanced significantly, yet many patients face unintended consequences beyond tumor eradication. One of the most critical concerns is the impact of chemotherapy on skeletal health. Understanding how cytotoxic agents influence the delicate balance of bone remodeling is essential for optimizing long-term outcomes. This article explores the multifaceted relationship between chemotherapy and bone density, examining underlying mechanisms, clinical evidence, and practical strategies to preserve skeletal integrity.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Chemotherapy-Induced Bone Loss

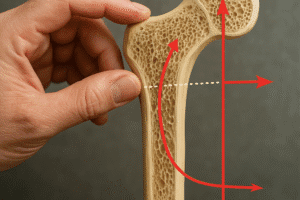

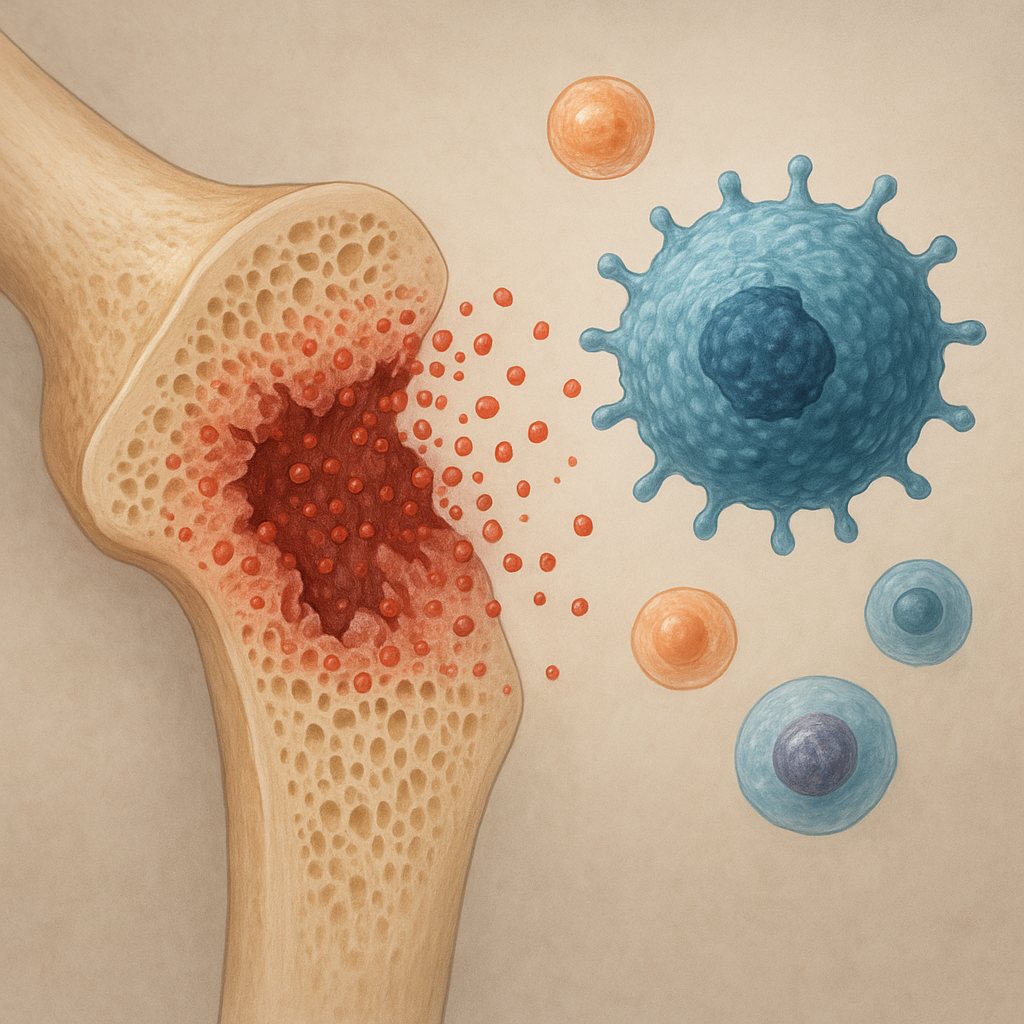

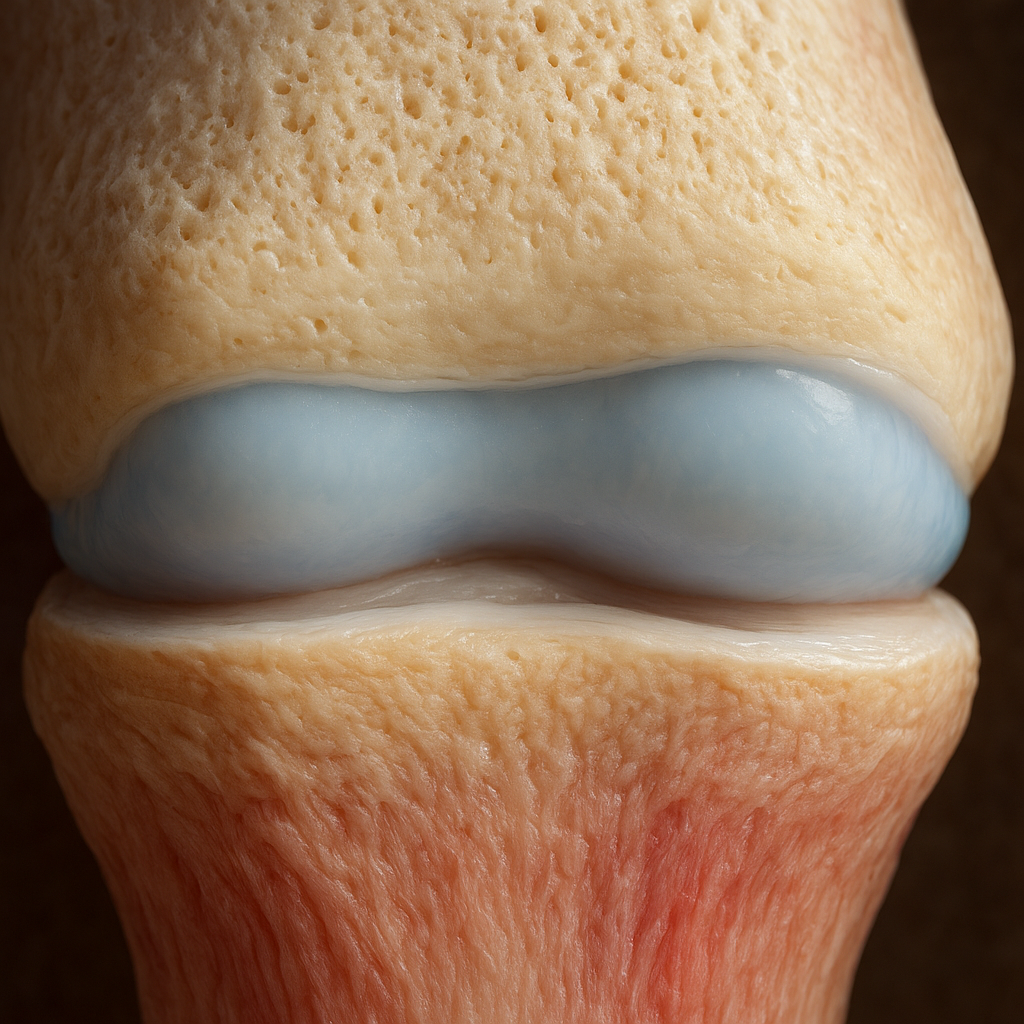

Cytotoxic regimens, while targeting rapidly dividing cancer cells, also affect healthy tissues. Bone remodeling relies on the coordinated activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Disruption of this balance can lead to osteopenia and eventually osteoporosis. Several mechanisms contribute to bone loss during and after chemotherapy:

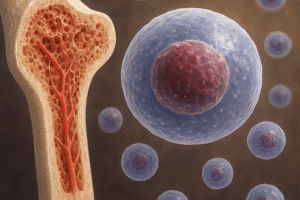

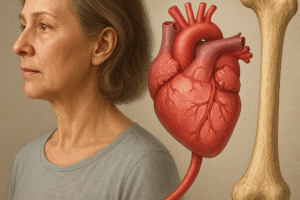

- Hormonal Alterations: Certain chemotherapeutic agents induce ovarian or testicular failure, reducing circulating estrogen and testosterone. These sex hormones normally inhibit osteoclast activity and support osteoblast survival. Their deficiency accelerates bone resorption.

- Direct Toxicity to Bone Cells: Agents such as methotrexate and cyclophosphamide can damage osteoblast progenitors in the bone marrow microenvironment, diminishing bone formation.

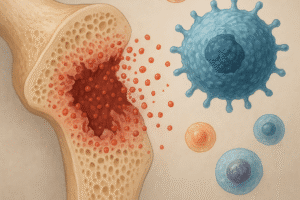

- Inflammatory Cytokines: Chemotherapy often triggers release of proinflammatory mediators (eg, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α) that stimulate osteoclastogenesis. Elevated cytokine levels amplify bone breakdown.

- Impaired Calcium Homeostasis: Gastrointestinal side effects like mucositis or diarrhea can reduce dietary calcium absorption. Additionally, chemotherapy-induced renal toxicity may impair vitamin D metabolism, disrupting calcium–phosphate balance.

- Oxidative Stress: Reactive oxygen species generated by many chemotherapeutic drugs damage osteoblasts and promote osteoclast differentiation, further tipping the scale toward bone resorption.

Clinical Evidence and Risk Factors

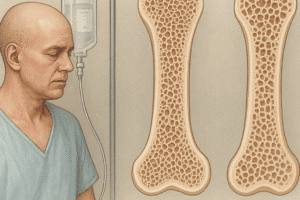

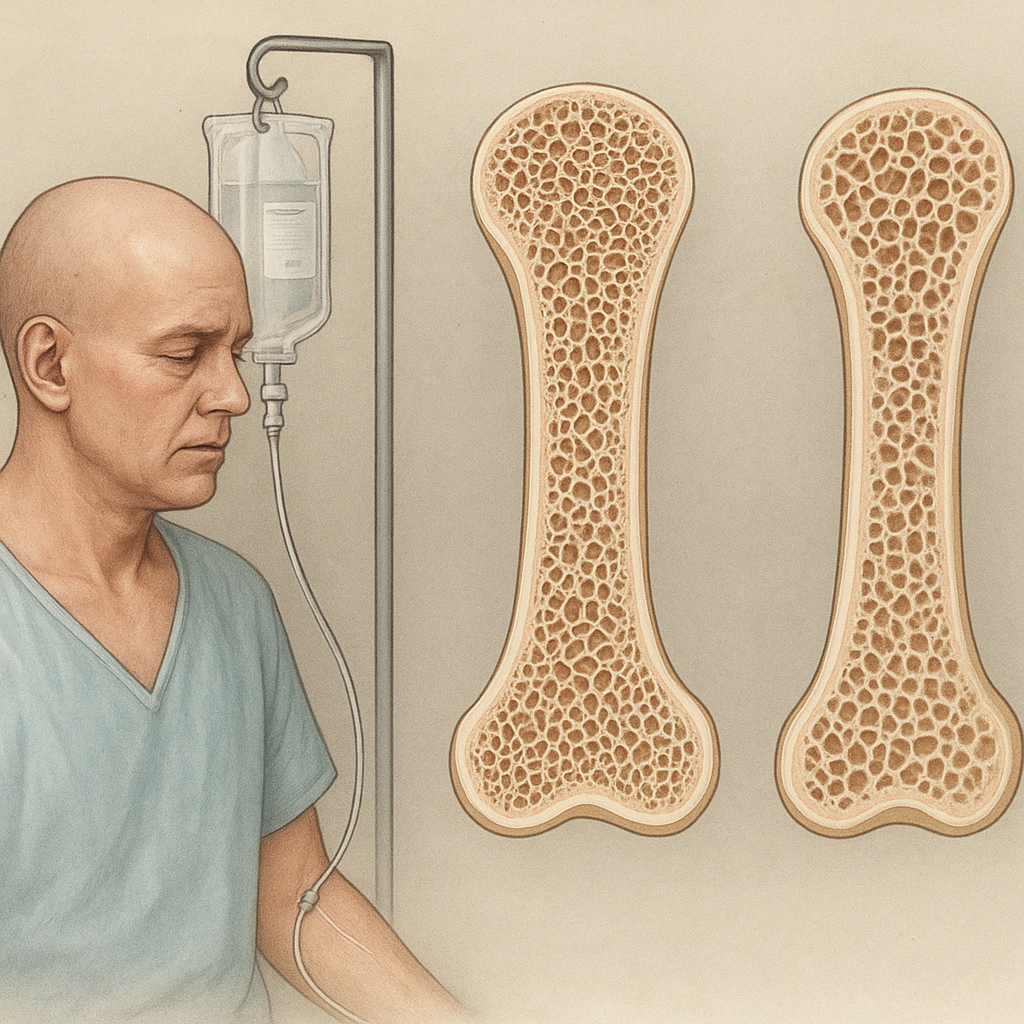

Numerous studies have documented significant bone loss among patients undergoing chemotherapy. The severity depends on therapy type, duration, and patient-specific factors. Key observations include:

- Breast cancer survivors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy often experience annual bone mineral density (BMD) declines of 2–5%, especially if treatment induces early menopause.

- Men with testicular cancer receiving platinum-based regimens show increased rates of osteopenia within two years of treatment completion.

- Patients with hematological malignancies undergoing high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation face accelerated bone loss, with fracture risk rising markedly in the first year post-transplant.

Several risk factors exacerbate susceptibility to treatment-related bone loss:

- Age: Elderly patients already have reduced bone reserve and slower osteoblast function.

- Baseline Bone Health: Preexisting osteopenia or vitamin D deficiency predisposes to further deterioration.

- Concurrent glucocorticoid use for antiemetic or anti-inflammatory purposes compounds bone loss.

- Lifestyle factors such as smoking, excessive alcohol intake, and physical inactivity limit the body’s capacity to maintain skeletal mass.

Prevention and Management Strategies

Proactive measures can mitigate chemotherapy-induced skeletal damage. A multidisciplinary approach integrates pharmacological interventions, dietary optimization, and exercise.

Pharmacotherapy

- Bisphosphonates (eg, zoledronic acid, alendronate): These antiresorptive agents inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone breakdown. Regular infusion or oral dosing during chemotherapy can stabilize or increase BMD.

- Denosumab: A monoclonal antibody against RANKL, it prevents osteoclast formation. Denosumab has demonstrated efficacy in preserving bone mass in cancer patients on therapy.

- Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs): In hormone-sensitive cancers, SERMs like raloxifene may offer bone protection without increasing cancer risk.

- Teriparatide: A recombinant form of PTH, it stimulates bone formation. Though its use in oncology patients is still under investigation, early data suggest benefit when antiresorptives are contraindicated.

Nutrition and Supplements

- Ensure adequate intake of calcium (1000–1200 mg daily) through diet or supplements.

- Maintain optimal vitamin D levels (30–50 ng/mL) to facilitate calcium absorption. Supplementation of 800–2000 IU per day is often required.

- Encourage a balanced diet rich in lean protein, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains to provide cofactors like magnesium and vitamin K, essential for bone matrix integrity.

Physical Activity

Weight-bearing and resistance exercises stimulate osteoblast activity and improve muscle strength, reducing fall risk. Tailoring an exercise program to individual fitness levels, treatment side effects, and clinical status is crucial. Activities may include:

- Walking or jogging

- Resistance band training

- Balance and posture exercises

Emerging Research and Future Directions

Ongoing investigations aim to refine our understanding of chemotherapy’s skeletal impact and develop targeted interventions. Promising avenues include:

- Biomarker Identification: Discovering reliable markers of bone turnover could enable early detection of patients at greatest risk and guide individualized therapy.

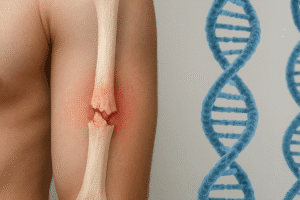

- Novel Therapeutics: Agents that modulate signaling pathways (eg, Wnt/β-catenin, sclerostin inhibitors) show potential to enhance bone formation without promoting tumor growth.

- Gut Microbiome Modulation: Emerging data suggest that chemotherapy-induced dysbiosis affects nutrient absorption and systemic inflammation. Probiotics or prebiotics may offer indirect bone protection.

- Genetic Profiling: Identifying polymorphisms that influence drug metabolism and bone health could personalize preventive strategies and minimize adverse effects.