The interplay between bone density and gender has long intrigued researchers, clinicians, and public health experts. Differences in skeletal strength, peak bone mass attainment, and age-related bone loss trajectories contribute to varying patterns of skeletal fragility in men and women. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for developing tailored prevention strategies, optimizing diagnostic approaches, and improving long-term musculoskeletal health. This article examines the biological underpinnings, measurement methods, contributory factors, and intervention strategies related to gender-based disparities in bone density.

Understanding Bone Density and its Measurement

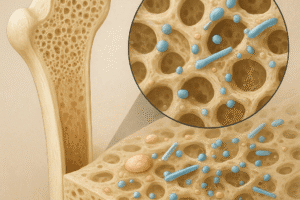

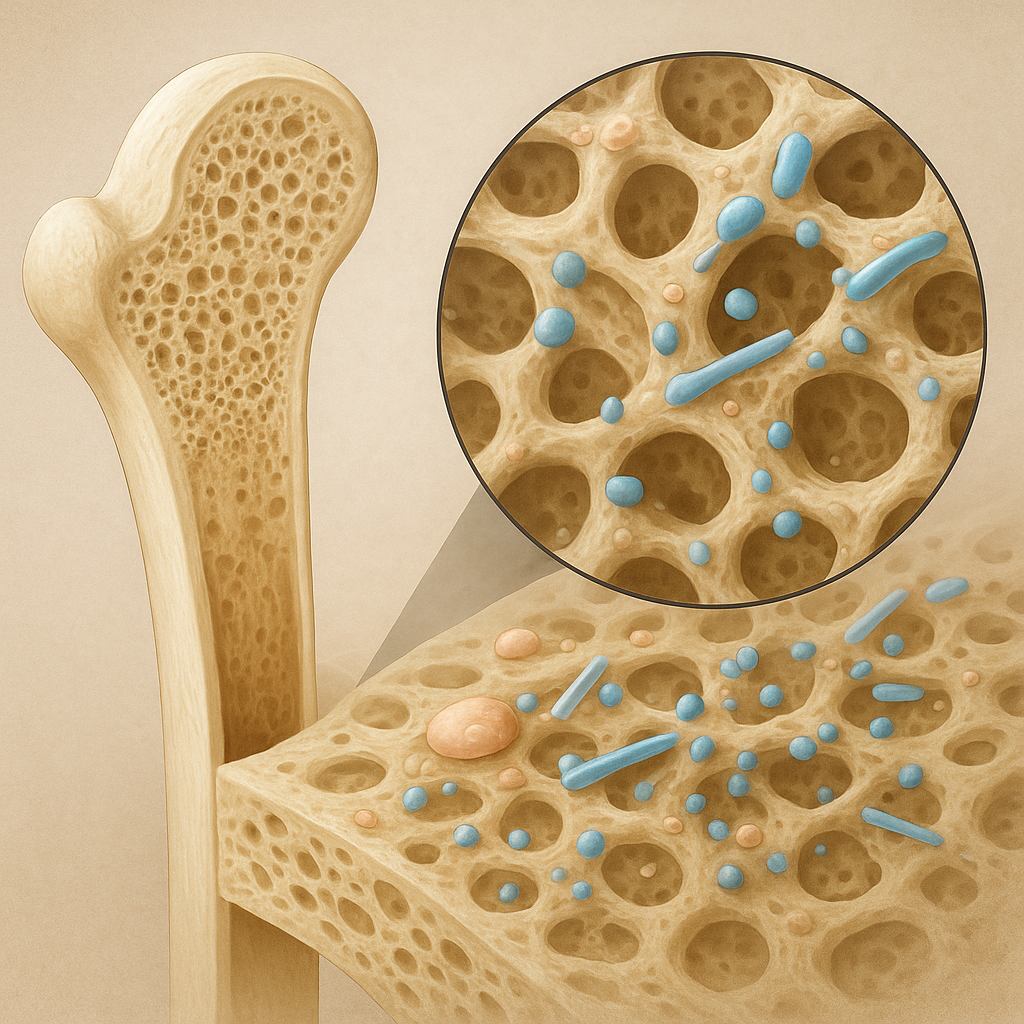

Bone density refers to the amount of mineralized tissue packed into a given bone volume. The most widely used clinical tool to assess this parameter is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which provides an areal bone mineral density (aBMD) value in grams per square centimeter. In research settings, peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) and high-resolution pQCT (HR-pQCT) quantify volumetric density and microarchitectural features. Key metrics include:

- Trabecular BMD: Reflecting the spongy interior, more metabolically active and sensitive to hormonal shifts.

- Cortical BMD: Denser outer shell, critical for mechanical strength and resistant to microdamage.

- Bone Mineral Content (BMC): Total mineral mass within a scanned region.

Peak bone mass typically occurs in the third decade of life, influenced by genetics, nutrition, physical activity, and endocrine factors. After peak achievement, bone remodeling shifts towards net loss, predisposing individuals to fractures if density falls below critical thresholds. The World Health Organization defines osteoporosis based on DXA-derived T-scores, comparing to a young reference population. However, gender-specific T-score reference data ensure more accurate risk stratification.

Gender-specific Biological Factors Influencing Bone Health

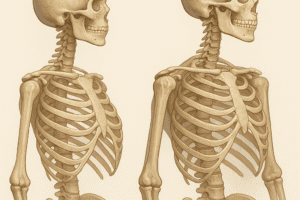

Men and women differ in skeletal geometry, hormonal milieu, and timing of bone loss. These variations underlie the observed discrepancies in fracture incidence and severity.

Hormonal Regulation

In women, the decline of estrogen during menopause accelerates bone resorption. Estrogen modulates osteoclast apoptosis, cytokine expression, and RANK/RANKL signaling. Estrogen deficiency leads to increased osteoclast activity, reduced trabecular connectivity, and rapid cortical thinning. Conversely, men experience a gradual decrease in testosterone with age; some is aromatized into estrogen, helping maintain bone homeostasis. Severe hypogonadism, either primary or secondary, predisposes men to osteoporosis but at older ages compared to postmenopausal women.

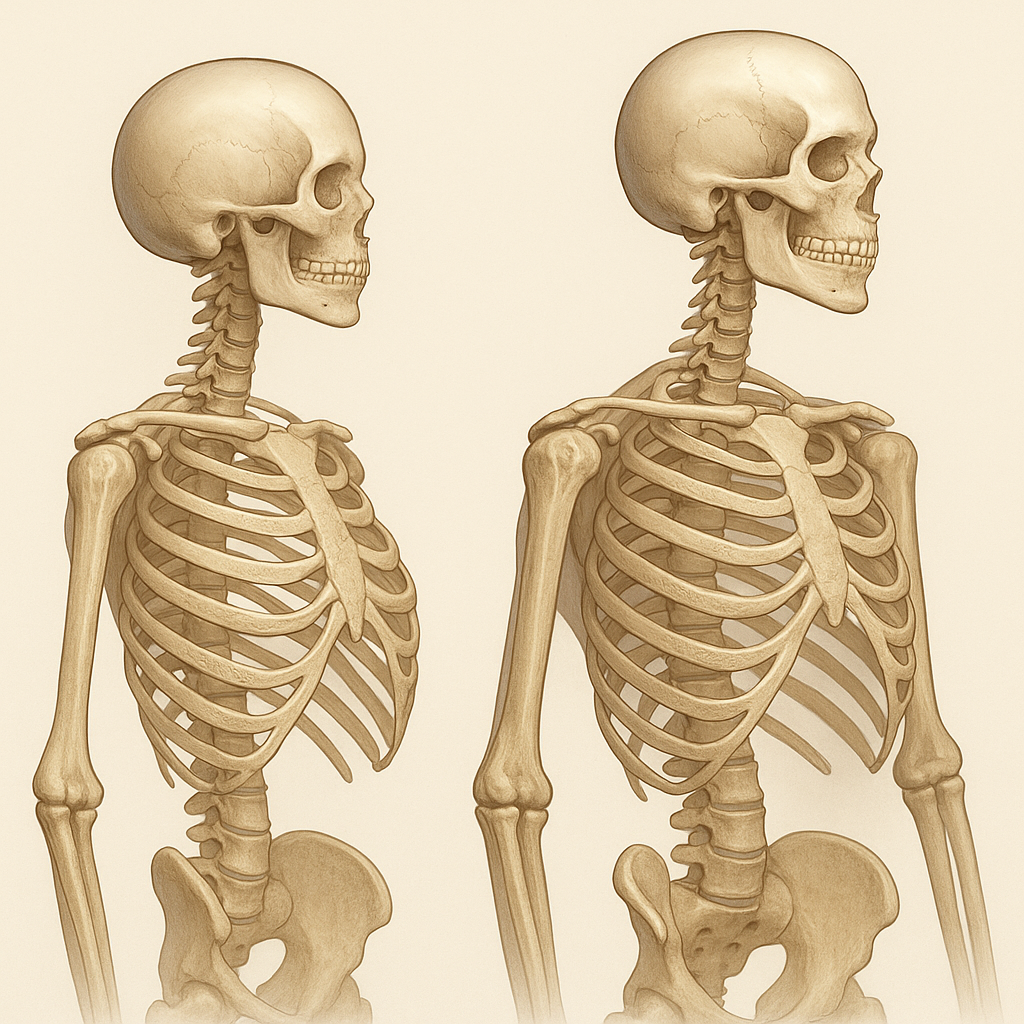

Peak Bone Mass and Skeletal Geometry

- Men generally achieve a 10–15% higher peak bone mass than women, due to larger bone size and greater periosteal apposition during adolescence.

- Women tend to have thinner cortices but relatively more trabecular bone; this architecture predisposes to vertebral compression fractures when density declines.

- Differences in hip geometry influence fracture patterns: women more often sustain femoral neck fractures, while men more frequently experience hip shaft fractures.

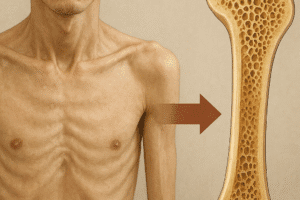

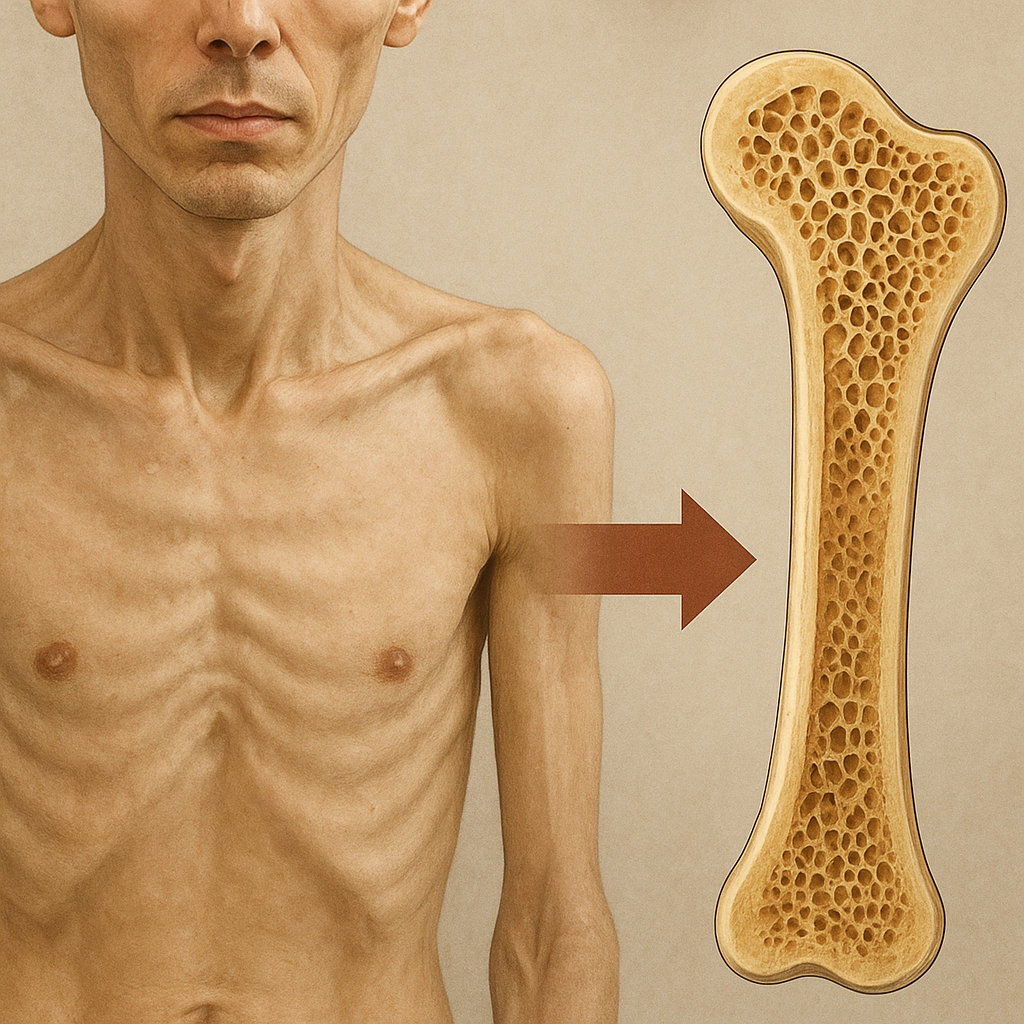

Consequences of Low Bone Density in Men and Women

Low bone density translates into increased fracture risk, morbidity, and healthcare costs. Epidemiological studies reveal that although women have a higher lifetime risk of osteoporosis-related fractures, men exhibit greater post-fracture mortality. Key observations include:

- Postmenopausal women can lose up to 2–3% of bone mass per year during early menopause, significantly elevating vertebral and wrist fracture risk.

- Men may underdiagnose osteoporosis, as screening guidelines historically focused on women; thus, male fractures often occur in the setting of secondary causes such as glucocorticoid excess or alcohol abuse.

- Hip fractures in men are associated with a 1.5 to 2 times higher 1-year mortality compared to women, partly due to comorbidities and delayed rehabilitation.

Additionally, low bone density affects quality of life, leading to chronic pain, reduced mobility, and loss of independence. Early identification of individuals at high risk—using tools like FRAX adjusted for gender—enables timely interventions.

Strategies for Maintaining and Improving Bone Density

Prevention and treatment of osteoporosis demand a multifaceted approach combining lifestyle, nutritional, pharmacological, and sometimes hormonal therapies. Gender-tailored strategies optimize outcomes by addressing specific risk profiles.

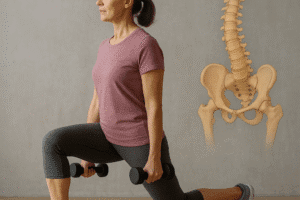

Lifestyle and Exercise

- Weight-bearing exercise: Activities such as walking, jogging, and stair climbing stimulate bone formation by inducing mechanical strain.

- Resistance training: Progressive loading enhances muscle mass and bone strength, particularly beneficial for postmenopausal women and aging men with sarcopenia.

- Fall prevention programs: Balance training, home hazard assessment, and vision correction reduce fracture risk in older adults of both genders.

Nutrition and Supplements

Adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D supports bone mineralization. Recommended daily intakes range from 1,000 to 1,200 mg of calcium and 600 to 800 IU of vitamin D, with higher doses considered in deficient individuals. Protein adequacy (1.0–1.2 g/kg body weight) ensures osteoblast function. Emerging evidence suggests roles for magnesium, vitamin K2, and omega-3 fatty acids in modulating bone turnover.

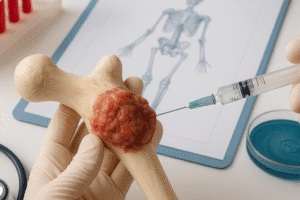

Pharmacological Interventions

- Bisphosphonates: Inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption; indicated for both genders with T-scores ≤ –2.5 or high fracture risk.

- Denosumab: A RANKL inhibitor reducing osteoclast differentiation; effective in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy.

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): Provide estrogenic benefits to bone without stimulating breast or uterine tissue; primarily used in women.

- Teriparatide: Recombinant PTH analog that stimulates bone formation; reserved for severe osteoporosis in men and women.

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT): Estrogen or combined estrogen-progestin regimens help maintain bone density in early postmenopausal women but require careful risk-benefit assessment.

Emerging therapies, such as sclerostin inhibitors, show promise in enhancing bone formation, potentially benefiting patients of both genders with low bone mass refractory to conventional agents.

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Interdisciplinary research is vital to unravel sex-specific genetic determinants of bone strength, the role of the gut microbiome in mineral absorption, and novel biomarkers for fracture risk. Personalized medicine approaches—incorporating genetic profiling, advanced imaging, and predictive analytics—may revolutionize how clinicians prevent and treat osteoporosis in men and women. Moreover, public health initiatives must promote awareness of male osteoporosis, encourage early screening, and destigmatize bone health discussions across genders.