Bone infections, medically known as osteomyelitis, pose significant challenges in both diagnosis and treatment. This article explores the multifaceted nature of these infections, delving into their underlying mechanisms, clinical features, and modern management strategies.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The development of a bone infection often begins when microorganisms gain access to the skeletal system. While any microbe can theoretically invade bone tissue, certain pathogens exhibit a pronounced affinity for osseous structures. Understanding these causative agents and their modes of entry is crucial for effective intervention.

Common Causative Organisms

- Staphylococcus aureus – the most frequent culprit, especially in hematogenous osteomyelitis.

- Streptococcus species – often implicated in secondary bone infections following soft tissue involvement.

- Gram-negative bacilli – notably Pseudomonas aeruginosa in diabetic foot infections.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis – responsible for spinal involvement (Pott’s disease).

- Fungi – such as Candida or Aspergillus in immunocompromised patients.

Mechanisms of Spread

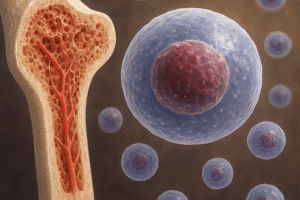

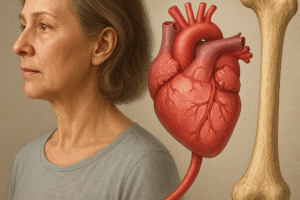

- Hematogenous dissemination – microbes enter the bloodstream through distant infections and seed bone.

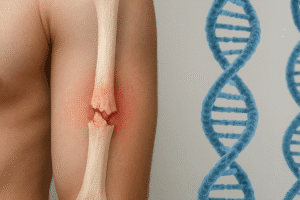

- Direct inoculation – traumatic injuries, orthopedic surgery, or injections breach bony defenses.

- Contiguous spread – from adjacent soft tissue infections or ulcers, especially in diabetic or vascular-insufficient individuals.

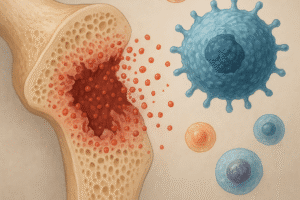

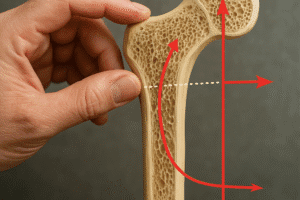

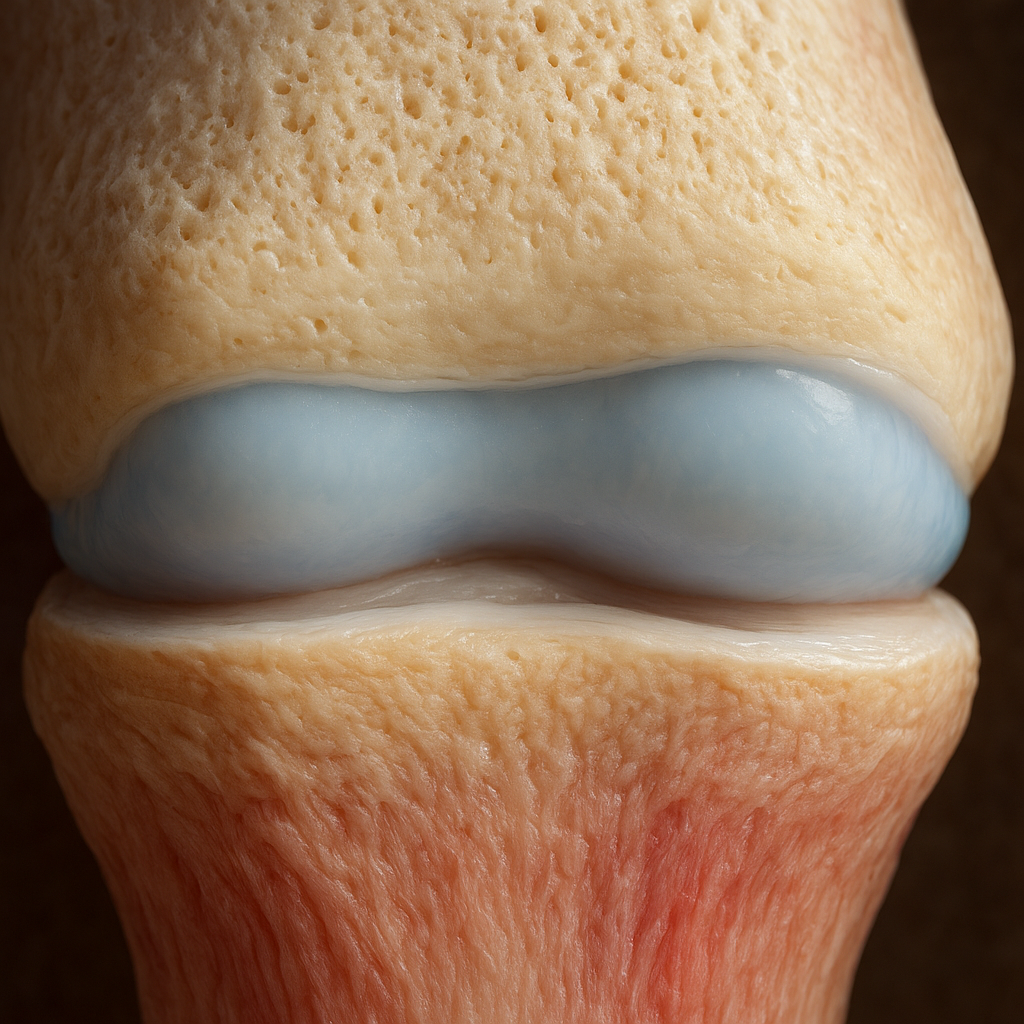

Pathophysiological Changes

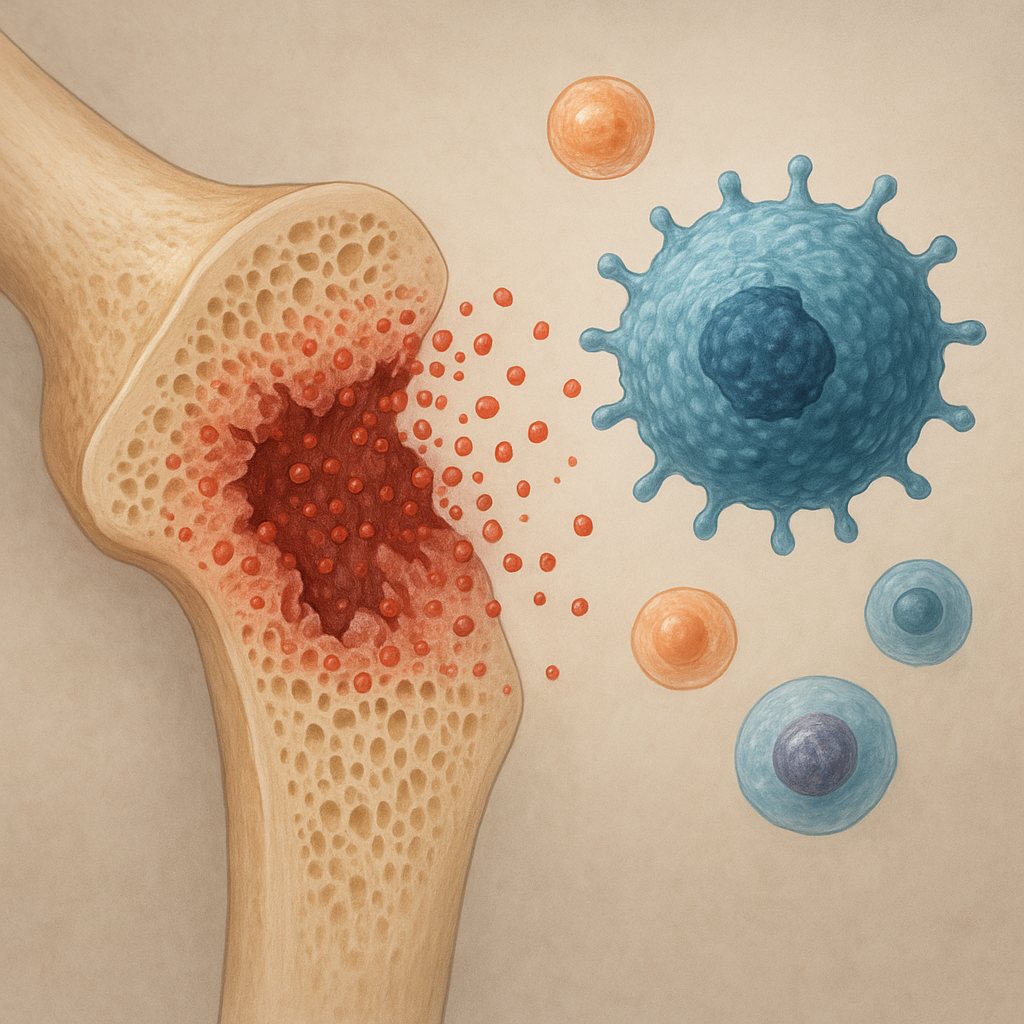

Once in the bone, pathogens elicit a robust inflammatory response. Neutrophils release enzymes and reactive oxygen species, leading to bone necrosis. Over time, dead bone fragments (sequestra) can form, while new bone (involucrum) encases the infected area, complicating eradication efforts. Microbial biofilm formation on bone surfaces and implanted hardware further shields bacteria from antibiotics and immune cells.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Recognizing osteomyelitis early is key to reducing morbidity. Symptoms can range from subtle, low-grade fevers to acute, severe pain and systemic toxicity. A high index of suspicion is particularly important in patients with risk factors such as diabetes, intravenous drug use, or recent orthopedic interventions.

Clinical Features

- Localized pain, often deep-seated and exacerbated by movement.

- Swelling, erythema, and warmth overlying the affected bone.

- Systemic signs – fever, malaise, or elevated white blood cell count.

- Draining sinus tracts in chronic cases.

Diagnostic Modalities

- Laboratory studies:

- C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) – sensitive but not specific.

- Blood cultures – identify hematogenous spread organisms in up to 60% of acute cases.

- Imaging:

- X-rays – may show periosteal reaction or sequestra but can lag weeks behind symptom onset.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – the gold standard for early detection and soft tissue assessment.

- Computed tomography (CT) – useful for guiding biopsy and evaluating sequestra.

- Bone scintigraphy – high sensitivity but lower specificity.

- Bone biopsy – definitive diagnosis achieved through culture and histopathology of bone tissue.

Treatment and Management Strategies

Effective management of osteomyelitis relies on combining medical and surgical approaches tailored to the patient’s condition, pathogen profile, and anatomical considerations.

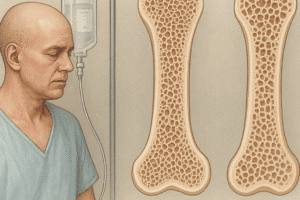

Antimicrobial Therapy

- Empirical antibiotic coverage – initiated promptly, targeting common gram-positive organisms until culture results are available.

- Culture-directed therapy – typically extended to 4–6 weeks for acute cases, and up to several months for chronic conditions.

- Selection of agents:

- Beta-lactams (e.g., nafcillin, cefazolin) for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus.

- Vancomycin or daptomycin for MRSA infections.

- Fluoroquinolones for gram-negative rods, particularly in Pseudomonas osteomyelitis.

- Antitubercular therapy for spinal TB.

Surgical Interventions

In many cases, debridement of necrotic bone is essential. Surgical goals include:

- Removal of sequestra and infected soft tissues.

- Restoration of blood flow to enhance antibiotic delivery.

- Stabilization of skeletal defects using external fixators or bone grafts.

- Implant removal if hardware-associated infection is present.

Adjunctive Therapies

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy – may improve oxygenation and aid in wound healing.

- Local antibiotic delivery – antibiotic-impregnated beads or spacers achieve high local concentrations.

- Negative-pressure wound therapy – helps manage soft tissue defects and promotes granulation.

Prevention and Future Directions

Reducing the incidence of bone infections involves both clinical vigilance and patient education. Perioperative prophylaxis, strict aseptic techniques, and optimization of comorbid conditions (e.g., glycemic control in diabetics) are fundamental preventive measures. Emerging research explores novel strategies such as antimicrobial coatings on implants, bacteriophage therapy, and immunomodulatory agents aimed at disrupting biofilm formation.

Advances in molecular diagnostics promise earlier and more precise pathogen identification, while developments in regenerative medicine seek to revolutionize bone reconstruction following debridement. Multidisciplinary collaboration between orthopedists, infectious disease specialists, radiologists, and microbiologists remains the cornerstone of tackling the complex challenge of osteomyelitis.