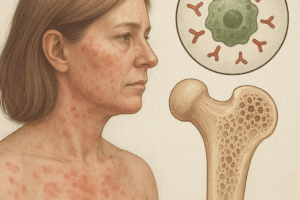

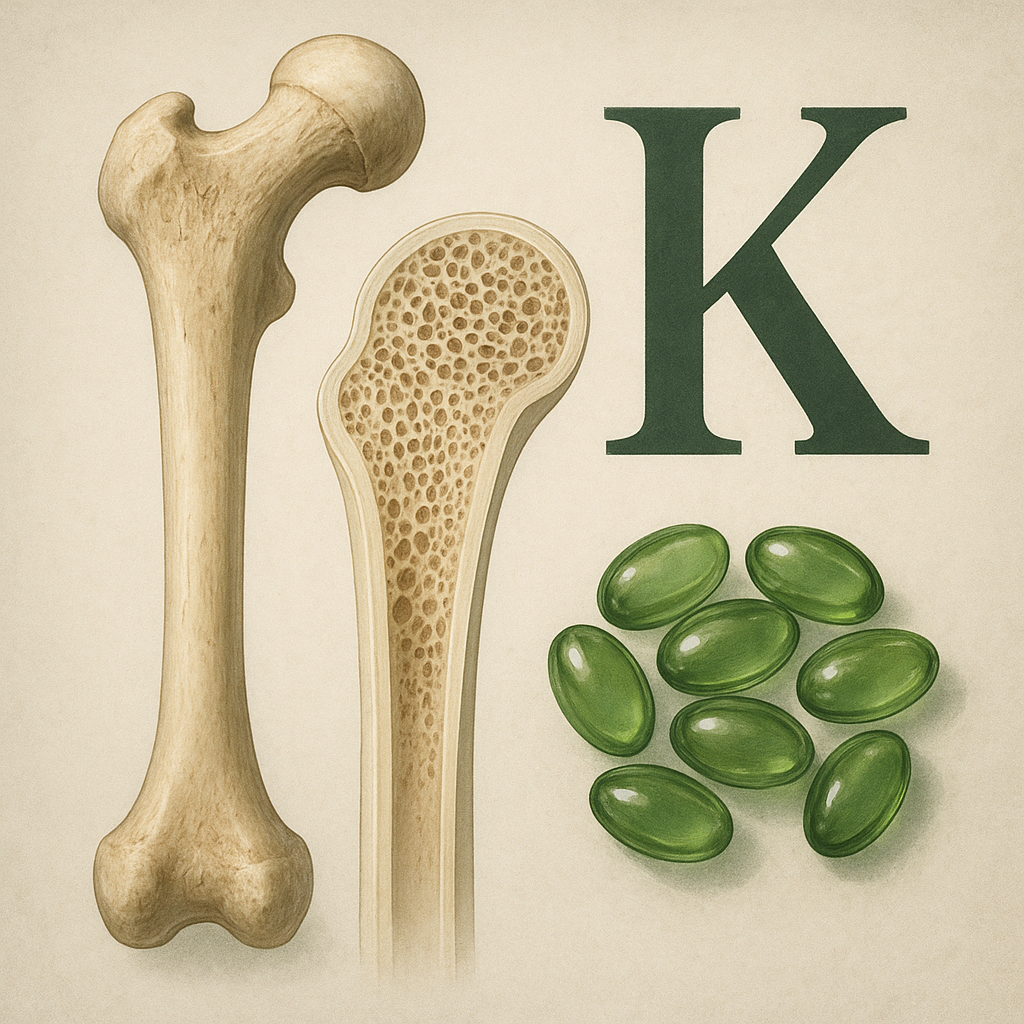

Vitamin K has emerged as a pivotal nutrient in the field of bone health, influencing the structural integrity and function of the skeletal system. Initially recognized for its role in blood coagulation, its significance in bone metabolism has become increasingly apparent. This article explores the biochemical pathways, clinical research, dietary considerations, and future directions related to the relationship between vitamin K and skeletal homeostasis.

Biochemical Mechanisms of Vitamin K in Bone Metabolism

Vitamin K exists in two primary forms: phylloquinone (vitamin K1) and menaquinone (vitamin K2). Both act as essential cofactors for the enzyme γ-glutamyl carboxylase, which catalyzes the post-translational modification of specific bone proteins. This carboxylation process adds a carboxyl group to glutamic acid residues, transforming them into γ-carboxyglutamic acid (Gla) residues that can bind calcium ions with high affinity.

Osteocalcin Carboxylation

- Osteocalcin, a non-collagenous protein secreted by osteoblasts, requires full carboxylation to become biologically active.

- Carboxylated osteocalcin binds hydroxyapatite crystals in bone matrix, enhancing mineralization and improving bone strength.

- Under-carboxylated osteocalcin has reduced affinity for calcium, potentially compromising bone quality.

Matrix Gla Protein (MGP) Activation

Matrix Gla protein is another vitamin K–dependent protein that inhibits vascular and cartilage calcification. When carboxylated, MGP prevents inappropriate calcium deposition in soft tissues, thus maintaining vascular and skeletal health.

Clinical Evidence Linking Vitamin K to Bone Health

Numerous observational studies and randomized controlled trials have evaluated the impact of vitamin K intake on bone mineral density (BMD), fracture risk, and osteoporosis management.

Observational Studies

- Populations with higher dietary intake of vitamin K, especially menaquinone, often exhibit increased BMD and reduced fracture rates.

- Cross-sectional analyses reveal associations between low serum vitamin K levels and elevated markers of bone turnover.

- Prospective cohort studies suggest that sufficient vitamin K status is inversely correlated with hip and vertebral fracture incidence.

Randomized Controlled Trials

Intervention trials have investigated phylloquinone and various menaquinone subtypes (MK-4, MK-7) supplementation in postmenopausal women and elderly men:

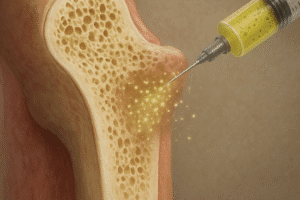

- Supplementation with MK-7 (180–360 µg/day) over 12 months resulted in significant increases in carboxylated osteocalcin and modest improvements in BMD at the lumbar spine.

- Studies using high-dose MK-4 (45 mg/day) reported a reduction in vertebral fractures compared to control groups, although the required doses exceed typical dietary levels.

- Some trials combining vitamin D and vitamin K show synergistic effects, suggesting that co-supplementation may yield greater benefits for bone turnover markers and fracture prevention.

Dietary Sources and Supplementation Strategies

Ensuring adequate intake of vitamin K is crucial for optimal bone metabolism. Dietary guidelines emphasize both plant-based and fermented food sources to achieve a balanced profile of phylloquinone and menaquinones.

Phylloquinone-Rich Foods

- Leafy green vegetables (e.g., kale, spinach, collard greens) are abundant in phylloquinone, with one cup often providing over 100 µg.

- Broccoli and Brussels sprouts contribute additional vitamin K1 along with fiber and antioxidants.

- Oils such as soybean and canola offer moderate amounts of phylloquinone suitable for cooking.

Menaquinone (K2) Sources

- Fermented foods like natto (Japanese fermented soybeans) deliver high concentrations of MK-7, sometimes exceeding 1000 µg per serving.

- Dairy products (cheese and yogurt) and certain meats contain MK-4, although at lower levels than natto.

- Supplement formulations often provide standardized doses of MK-7 for consistent bioavailability and extended half-life.

Recommended Intake and Safety

The Adequate Intake (AI) for vitamin K varies by age and sex, generally around 90 µg/day for women and 120 µg/day for men. While excess intake of vitamin K1 or K2 has not been linked to major toxicity, individuals on anticoagulant therapy should monitor vitamin K consumption to maintain stable coagulation parameters.

Emerging Research and Future Perspectives

Ongoing research aims to deepen our understanding of vitamin K’s role in bone and extra-skeletal health, exploring novel therapeutic applications and mechanistic insights.

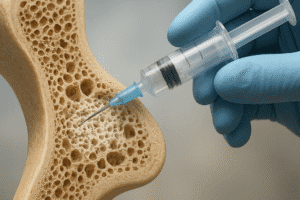

Vitamin K Analogues and Bone-Targeted Therapies

- Development of synthetic analogues to maximize bone-specific carboxylation without affecting coagulation.

- Nanoparticle-based delivery systems designed to target osteoblasts or bone marrow environments.

- Combination therapies pairing vitamin K with other anabolic agents such as parathyroid hormone or sclerostin inhibitors.

Genetic Variations and Personalized Nutrition

Genetic polymorphisms in VKORC1 (vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1) and GGCX genes may influence individual responses to dietary vitamin K and supplementation. Future strategies may integrate nutrigenomics to tailor intake recommendations.

Vitamin K and Age-Related Bone Disorders

Researchers are investigating how age-associated changes in microbiota composition affect menaquinone production, potentially linking gut health to bone resilience. Trials are underway to assess whether probiotic interventions can augment endogenous K2 synthesis and improve skeletal outcomes.