Paget’s Disease of Bone is a chronic skeletal disorder characterized by localized areas of abnormal bone turnover. This condition disrupts the normal balance of bone formation and resorption, leading to structural deformities, pain, and potential complications. Understanding the underlying mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and management options is essential for optimizing patient outcomes and improving quality of life.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

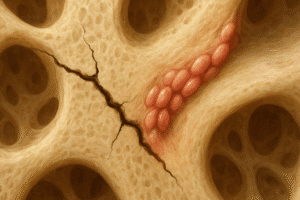

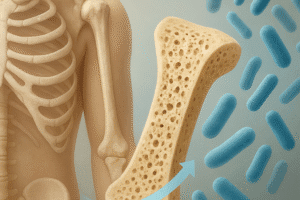

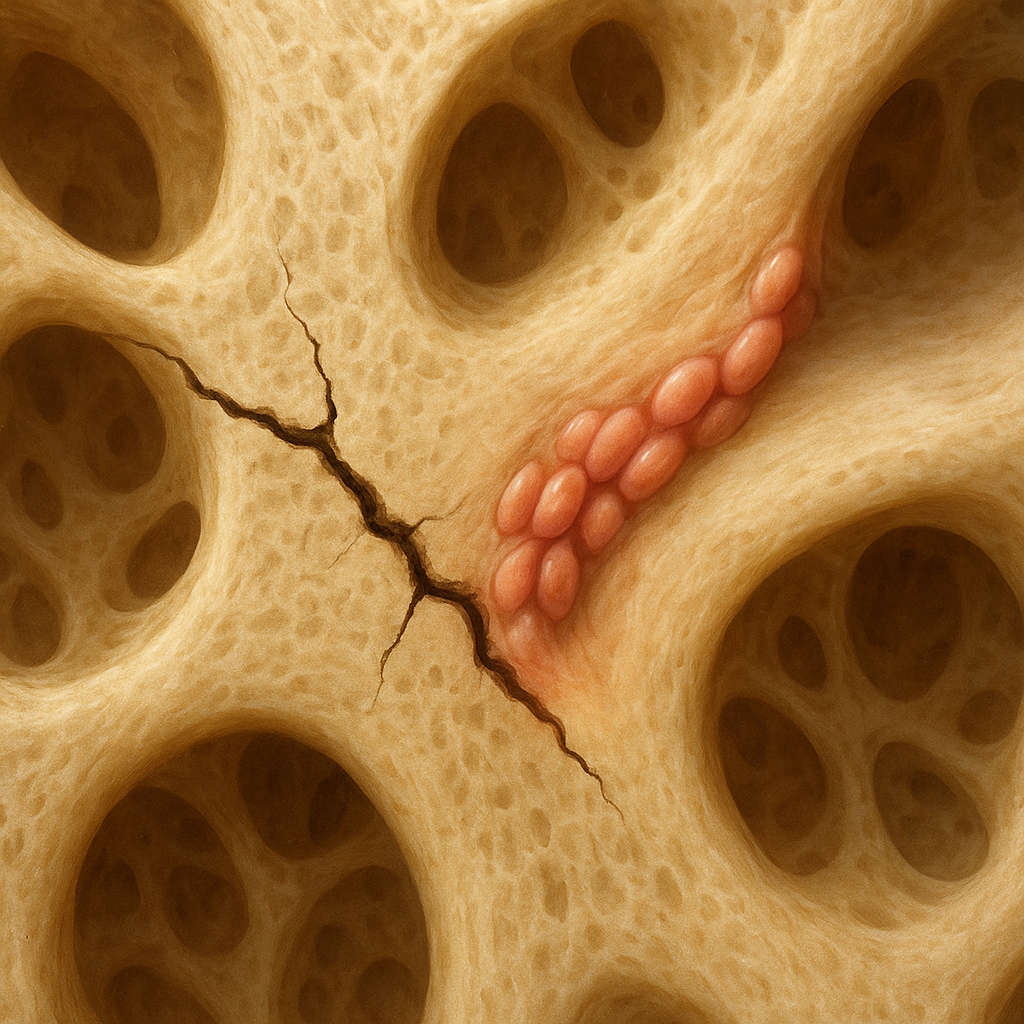

At its core, Paget’s disease involves a dysregulation of bone remodeling, the continuous process by which old bone is replaced by new. In affected regions, there is hyperactivity of osteoclasts, the cells responsible for bone resorption, followed by an increase in osteoblasts activity to rebuild the bone. However, this new bone is structurally disorganized, leading to weakened areas prone to cracks and deformities.

The precise triggers for this imbalance remain under investigation. Several studies point to a combination of genetic mutations and environmental factors. Familial clustering suggests an autosomal dominant pattern in some cases, with mutations in genes such as SQSTM1 affecting signaling pathways in bone cells. Environmental contributors may include viral infections, with paramyxovirus particles suspected but not definitively proven.

Histologically, Pagetic bone shows mosaic patterns of lamellar bone separated by irregular cement lines. Increased vascularity in pagetic lesions can sometimes lead to high-output cardiac failure in extensive disease due to arteriovenous shunting within the bone.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

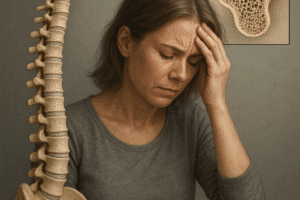

Many patients remain asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally after findings on imaging or routine blood tests. When symptoms occur, they often include:

- Bone pain, usually deep and aching.

- Deformities such as bowing of long bones or skull enlargement.

- Neurological complications from nerve compression.

- Hearing loss due to involvement of the temporal bone.

Laboratory evaluation frequently reveals elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels, reflecting increased osteoblastic activity. Other markers of bone turnover, such as urinary hydroxyproline, may also be elevated but are less specific.

Radiological studies are pivotal in confirming the diagnosis. Plain radiography demonstrates characteristic blade-of-grass or flame-shaped radiolucent areas in early disease, progressing to mixed radiolucent and sclerotic phases. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can assess the extent of bone expansion and neural involvement. A radionuclide bone scan highlights areas of increased uptake, revealing the full skeletal distribution of lesions.

Treatment Strategies

Management aims to control symptoms, reduce bone turnover, and prevent complications. The mainstay of therapy is pharmacological intervention with bisphosphonates, potent inhibitors of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption.

- Oral Bisphosphonates: Agents such as alendronate or risedronate are commonly prescribed in mild to moderate disease.

- Intravenous Bisphosphonates: Zoledronic acid offers a single high-dose infusion that can induce prolonged remission in many patients.

- Calcitonin: Once used frequently, this hormone is now reserved for those intolerant of bisphosphonates. It provides modest effects on bone turnover.

Additional measures include:

- Pain management through analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- Physical therapy to maintain mobility and strengthen surrounding musculature.

- Surgical intervention for fractures, joint replacement in advanced osteoarthritis, or decompression of neural structures.

Complications and Prognosis

Complications arise from structural changes in bone and its increased vascularity. Common issues include:

- Pathological fractures due to weakened bone architecture.

- Osteoarthritis in adjacent joints from altered load distribution.

- Hearing impairment when the skull base is involved.

- High-output cardiac failure in severe polyostotic disease.

Though rare, malignant transformation into osteosarcoma or fibrosarcoma can occur, typically in patients with long-standing disease. Early detection of unusual pain or rapid lesion growth warrants thorough evaluation to exclude neoplastic change.

With appropriate therapy, many patients achieve biochemical remission and stabilization of bone lesions. However, continued monitoring of serum markers and periodic imaging is recommended to detect recurrence or progression.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

Ongoing studies aim to refine understanding of Paget’s disease at the molecular level. Investigations into the RANK/RANKL/OPG signaling axis hold promise for targeted therapies beyond traditional bisphosphonates. Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody against RANKL, is under evaluation for patients with contraindications to current treatments.

Genetic profiling may enable personalized risk assessment, identifying individuals predisposed to early-onset or severe disease. In parallel, advanced imaging modalities and bone turnover markers are being validated for more sensitive detection of disease activity and response to therapy.

Ultimately, integrating genetic, biochemical, and imaging data could foster a precision medicine approach, tailoring intervention strategies to each patient’s unique disease profile.