Bone is a frequent target of metastatic spread due to its rich vascularization and supportive microenvironment. For patients with advanced cancers, bone metastasis represents a major clinical challenge, often leading to pain, fractures, and reduced quality of life. This article explores the mechanisms underlying tumor colonization of the skeletal system, the diagnostic tools available to detect bone involvement, and the current and emerging treatment modalities aimed at mitigating skeletal-related events and improving patient outcomes.

Pathophysiology of Bone Metastasis

The process of bone metastasis involves multiple steps. It begins with tumor cell detachment from the primary site, followed by intravasation into the circulatory system, survival in the bloodstream, extravasation into bone tissue, and colonization within the bone microenvironment. The “seed and soil” hypothesis originally described by Stephen Paget in 1889 underscores the importance of the bone as fertile soil for disseminated tumor seeds.

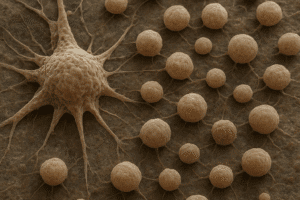

Role of the Bone Microenvironment

Within bone, interactions between tumor cells and resident cells such as osteoclasts and osteoblasts create a self-reinforcing cycle. Malignant cells secrete factors like parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) and interleukins, which stimulate osteoclast activation and bone resorption. The release of growth factors, including transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), from the degraded bone matrix further promotes tumor proliferation.

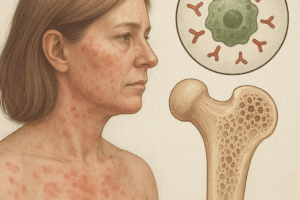

Osteolytic Versus Osteoblastic Metastases

Bone metastases can be broadly categorized as osteolytic or osteoblastic. Osteolytic lesions, common in breast and lung cancers, result from excessive bone breakdown, leading to hypercalcemia and increased fracture risk. In contrast, prostate cancer often induces osteoblastic lesions characterized by abnormal bone formation. However, many metastases display mixed features, reflecting complex interactions within the metastatic niche.

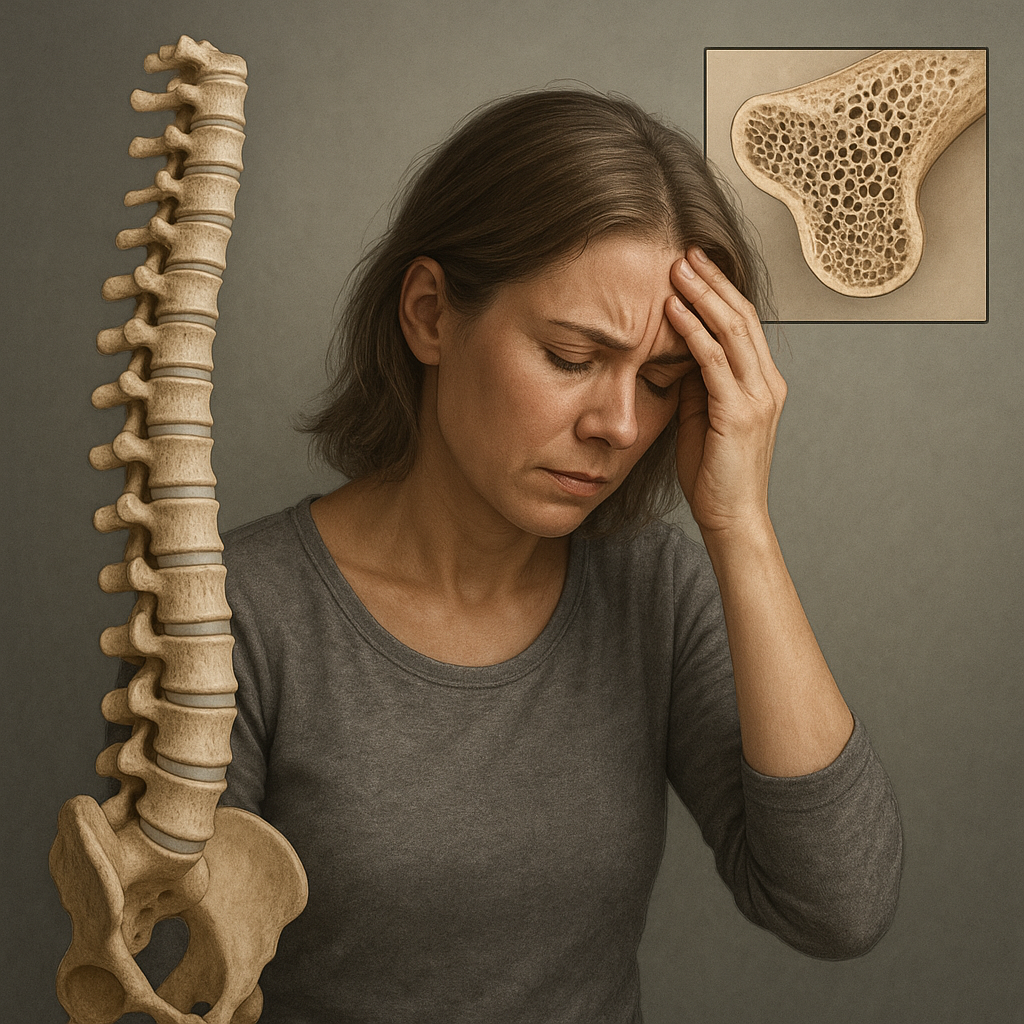

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

Patients with bone metastases frequently present with bone pain, which may be constant or activity-related. Additional complications include pathological fractures, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia of malignancy. Early recognition and accurate staging are critical to guide therapy and prevent debilitating skeletal-related events.

Imaging Modalities

- Conventional radiography: Useful for detecting lytic or blastic lesions but less sensitive for early disease.

- Bone scintigraphy: Highly sensitive for detecting multifocal metastases by highlighting areas of increased osteoblastic activity.

- Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Provide detailed anatomic information and are particularly valuable in assessing spinal involvement.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) combined with CT: Offers metabolic and structural insights, using tracers such as 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose.

Laboratory Assessments

- Serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase levels: May indicate bone turnover abnormalities.

- Markers of bone resorption: Such as C-terminal telopeptide (CTX).

- Markers of bone formation: Such as procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP).

Treatment Strategies and Future Directions

Management of bone metastasis aims to control tumor growth, alleviate pain, prevent fractures, and maintain function. A multidisciplinary approach often involves systemic therapies, bone-targeted agents, localized treatments, and supportive care.

Systemic Therapies

Cytotoxic chemotherapy and hormonal therapies remain cornerstones for many tumor types. In addition, targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in select patients with bone-involved disease.

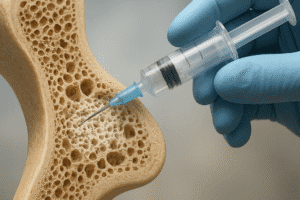

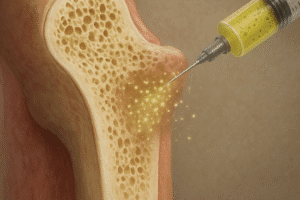

Bone-Targeted Agents

- Bisphosphonates: Inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, reducing the risk of skeletal-related events.

- Denosumab: A monoclonal antibody against RANKL, effectively preventing osteoclast activation.

- Radiopharmaceuticals: Agents such as radium-223 emit alpha particles to target bone metastases and relieve pain.

Localized Treatments

- External beam radiation therapy: Provides pain relief and local disease control.

- Surgical stabilization: Indicated for impending or actual fractures to restore structural integrity.

Emerging Approaches

Research continues to explore novel strategies, including:

- Inhibitors of tumor-derived exosomes to disrupt cell communication in the bone microenvironment.

- Bispecific antibodies targeting both tumor antigens and bone remodeling pathways.

- Gene therapy approaches to modulate the bone niche and enhance immune-mediated tumor clearance.

Advancements in genomic profiling and personalized medicine are paving the way toward tailored interventions for bone metastasis. By integrating knowledge of tumor biology with innovative therapeutic modalities, clinicians aim to further extend survival and quality of life for patients facing this complex condition.