Bone cement has become an indispensable element in the field of orthopedic surgery, providing a reliable medium for anchoring implants and restoring joint function. By understanding its composition, handling characteristics, and clinical applications, healthcare professionals can optimize surgical outcomes and enhance patient recovery.

Material Composition and Physical Properties

At the core of bone cement lies polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), a polymer that is widely recognized for its mechanical stability and biocompatibility. PMMA powder is mixed with a liquid monomer to create a viscous paste that hardens into a strong, load-bearing mass. Key components and their roles include:

- Polymer powder: Provides the particulate framework that, when combined with monomer, forms the hardened matrix.

- Monomer liquid: Initiates the polymerization reaction, controlling the setting time and working window.

- Initiators and activators: Trigger the exothermic curing reaction.

- Radiopacifiers: Barium sulfate or zirconium dioxide particles enable post-operative imaging assessment.

- Antibiotic additives: Gentamicin or vancomycin may be incorporated for local infection prophylaxis.

The polymerization process progresses through distinct phases: mixing, dough, working, and curing. Surgeons must be mindful of the viscosity profile during each stage to ensure optimal adhesion to both bone surfaces and implant substrates.

Mechanical Performance and Biocompatibility

Several physical properties govern the long-term success of cemented implants:

- Compressive strength: Typically surpasses natural cancellous bone, providing immediate load support.

- Elastic modulus: Must balance rigidity with a degree of flexibility to reduce stress shielding at the bone–cement interface.

- Porosity: Controlled to allow micro-interlocking with bone trabeculae without compromising mechanical integrity.

- Thermal conductivity: Elevated temperatures during curing require careful monitoring to prevent thermal necrosis of adjacent tissues.

Biocompatibility assessments confirm that PMMA is generally well-tolerated. However, the exotherm and residual monomer content can pose challenges. Modern formulations strive to minimize residual monomer levels to improve osteoconductivity and reduce cytotoxicity.

Clinical Applications in Orthopedic Surgery

Bone cement is most commonly applied in arthroplasty procedures, but its use extends to trauma fixation, vertebroplasty, and oncology surgeries. Common applications include:

Knee and Hip Arthroplasty

In total knee and hip replacements, bone cement serves as a grout between the prosthesis and host bone. Advantages include:

- Immediate implant stability, allowing early mobilization.

- Accommodation of minor anatomical irregularities in bone surfaces.

- Facilitation of load transfer when press-fit techniques are not viable.

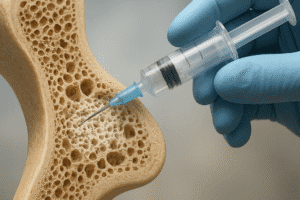

Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty

In spinal interventions, cement is injected percutaneously into vertebral bodies to restore vertebral height and alleviate pain caused by compression fractures. Key considerations:

- Low-viscosity cements penetrate trabecular bone more effectively.

- Balloon kyphoplasty creates a cavity to contain cement and reduce extravasation.

Oncologic and Trauma Fixation

In bone tumor resections, cement fills defects and provides structural support. In complex fractures, antibiotic-loaded cement beads act as spacers that both deliver localized therapy and maintain space for subsequent reconstruction.

Techniques for Optimizing Cement Application

Successful cementation hinges on meticulous surgical technique. The following steps outline best practices:

- Meticulous debridement of soft tissue and necrotic bone to promote intimate bone–cement contact.

- Bone bed preparation using pulsatile lavage to remove blood and marrow elements, enhancing interdigitation.

- Use of a cement restrictor in femoral canals to control the cement mantle thickness and minimize embolic risk.

- Vacuum mixing to reduce porosity and improve mechanical performance.

- Cement gun delivery for uniform pressurization and avoidance of voids.

- Timing the pressurization during the optimal working phase to achieve uniform distribution.

Surgeons should monitor intramedullary pressure and thermogenesis to prevent bone marrow embolism and thermal damage.

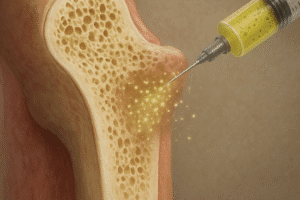

Antibiotic-Loaded Cement and Infection Control

Post-operative prosthetic joint infection remains a devastating complication. Antibiotic-loaded bone cements (ALBC) combine local antimicrobial delivery with mechanical fixation. Features include:

- High local antibiotic concentrations that exceed systemic dosing levels without systemic toxicity.

- Sustained release profiles to cover critical early post-operative periods.

- Compatibility with commonly used antibiotics such as gentamicin, tobramycin, and vancomycin.

Clinical studies demonstrate reduced infection rates in primary and revision arthroplasty when ALBC is used prophylactically. In two-stage exchange protocols, cement spacers loaded with high-dose antibiotics provide both structural support and targeted therapy.

Recent Advances and Future Directions

Innovations in bone cement technology aim to improve biological integration and long-term outcomes. Emerging trends include:

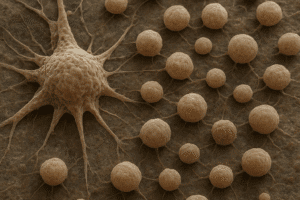

- Bioactive additives such as calcium phosphate or bioactive glass to promote osteointegration.

- Nanoparticle incorporation for enhanced mechanical properties and controlled drug release.

- Thermosetting hydrogels that reduce exotherm and mimic the viscoelastic behavior of natural bone marrow.

- Customized formulations for patient-specific factors, including bone quality and allergy profiles.

3D printing of cement constructs combined with imaging data may soon enable the fabrication of patient-tailored implants with optimized load distribution and bone ingrowth channels.

Challenges and Considerations for Surgeons

Despite its widespread use, bone cement is not without limitations. Surgeons must remain vigilant regarding:

- Cement mantle fractures and long-term fatigue failure, especially in high-demand patients.

- Allergic reactions to monomer or additives, which may necessitate alternative fixation methods.

- Thermal injury risk during polymerization, particularly in confined anatomical spaces.

- Potential for antibiotic resistance development with excessive or inappropriate use of ALBC.

Ongoing education, rigorous adherence to evidence-based protocols, and collaboration with materials scientists will be essential to overcome these hurdles and continue improving patient outcomes.