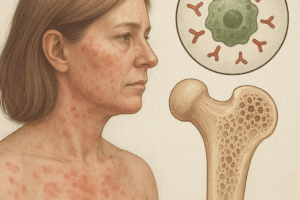

Bone fractures and metabolic bone diseases pose significant challenges to patients and healthcare providers alike. Integrating physical therapy within a multidisciplinary treatment plan is essential for facilitating efficient and effective bone repair. When bone tissue sustains damage, a carefully structured rehabilitation protocol not only accelerates the natural healing processes but also minimizes complications such as joint stiffness, muscle atrophy, and impaired functional mobility. This article explores the critical stages of bone healing, highlights the transformative role of physical therapy interventions, and outlines strategies for designing individualized recovery programs.

Understanding Bone Healing

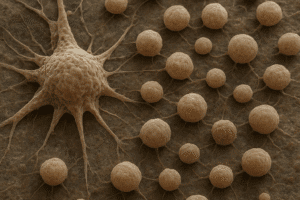

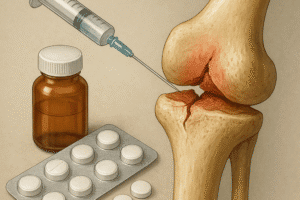

The complex process of bone repair unfolds through three overlapping phases: the inflammatory stage, the reparative stage, and the remodeling stage. Initially, hematoma formation and an influx of immune cells set the stage for cleansing damaged tissue and signaling resident cells to begin regeneration. Osteoblasts synthesize new bone matrix, while osteoclasts resorb damaged material, allowing for the gradual replacement of fibrous callus with mature lamellar bone. Optimizing these physiological events requires timely mobilization and load application to encourage proper alignment of collagen fibers and mineral deposition.

Phases of Bone Repair

- Inflammatory Phase: Characterized by pain, swelling, and vascular responses within the first week.

- Reparative Phase: Soft callus formation transitions to hard callus between weeks two and six.

- Remodeling Phase: Spanning several months, this phase restores structural integrity and mechanical strength.

The Impact of Physical Therapy

Physical therapy plays a pivotal role in achieving optimal outcomes by addressing deficits in mobility, strength, and neuromuscular control. Early intervention mitigates the risk of secondary complications such as joint contractures, chronic pain syndromes, and disuse osteoporosis. Through a combination of hands-on techniques and therapeutic exercise, physiotherapists facilitate a safe progression from protected weight-bearing to full functional loading, promoting bone mineral density and joint stability.

Early Mobilization

Following immobilization, gentle passive and active-assisted range of motion exercises support synovial fluid production and nutrition of articular cartilage. Controlled movements prevent periarticular fibrosis and encourage realignment of collagen fibers within the healing callus. Pain modulation techniques, including soft tissue mobilization and gentle traction, reduce muscle guarding and restore normal joint kinematics.

Load and Stress Application

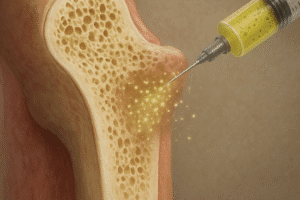

- Weight-Bearing Exercises: Graduated protocols stimulate osteogenic responses through mechanical stress.

- Manual Therapy: Joint mobilizations improve accessory movements and alleviate stiffness.

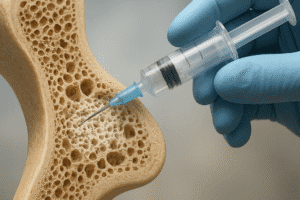

- Ultrasound: Low-intensity ultrasound may accelerate callus maturation by enhancing angiogenesis.

- Electrical Stimulation: Bone growth stimulators deliver microcurrents to encourage mineralization.

Designing a Physical Therapy Program

Creating an effective rehabilitation program requires a thorough initial assessment of the patient’s baseline function, fracture characteristics, and comorbidities. Goals must remain individualized, realistic, and time-bound to optimize compliance and engagement. By setting measurable milestones for pain reduction, range of motion, and functional tasks, clinicians can adjust interventions responsively as the patient progresses.

Initial Assessment and Goal Setting

An in-depth evaluation examines pain levels, joint integrity, muscle strength, and gait mechanics. Imaging findings provide insight into fracture stability and consolidation status. Collaborative goal setting involves patient education on weight-bearing precautions, activity limitations, and anticipated timelines for achieving daily living tasks.

Progressive Exercise Prescription

Exercise protocols evolve from non-weight-bearing isometric contractions to dynamic load-bearing movements. Emphasis should be placed on:

- Range of Motion: Active and passive exercises to restore joint flexibility.

- Strengthening: Closed-chain exercises that gradually increase axial loading.

- Proprioception: Balance and coordination drills to enhance neuromuscular control.

- Functional Training: Task-specific activities such as stair climbing and gait re-education.

Monitoring and Adjustment

Regular re-evaluation through objective measures—such as goniometry, dynamometry, and functional outcome scales—ensures that the program remains aligned with healing phases. Should signs of excessive pain or swelling emerge, the intensity of exercises is modified, and adjunctive modalities like cryotherapy or compression may be applied to control inflammation.

Technological Advances and Future Directions

Emerging innovations continue to refine bone rehabilitation strategies. Tele-rehabilitation platforms provide remote monitoring and guided exercise sessions, enhancing accessibility for patients in rural areas. Integrating virtual reality environments increases patient motivation through immersive, gamified tasks that target balance, coordination, and strength. Robotic exoskeletons and sensor-driven wearables offer precise feedback on movement quality, enabling real-time adjustments to therapeutic protocols. As digital health solutions evolve, interprofessional collaboration among orthopedic surgeons, physiotherapists, and biomedical engineers promises to accelerate recovery timelines and improve long-term musculoskeletal health.