Magnesium plays a pivotal role in maintaining healthy bones and supporting overall skeletal integrity. As an essential mineral, it contributes to various cellular processes and collaborates closely with other nutrients to regulate bone mineralization. Emerging research highlights the significance of magnesium not only as a cofactor in enzymatic reactions but also as a structural component within the bone matrix. This article delves into the intricate functions of magnesium in bone physiology, examines dietary sources and absorption mechanisms, explores clinical implications for bone disorders, and offers insights into recommended intake and supplementation strategies.

Physiological Roles of Magnesium in Bone Metabolism

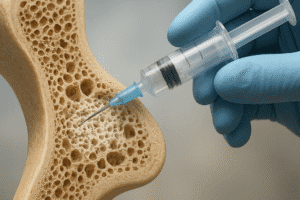

Approximately 60% of the body’s magnesium is stored in the skeleton, where it contributes to both the trabecular and cortical compartments. Magnesium is integral to bone formation, influencing the activity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, the cells responsible for building and resorbing bone respectively. It modulates the secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which in turn regulates serum calcium and phosphate concentrations—key elements for proper mineralization. By stabilizing the structure of hydroxyapatite crystals, magnesium ensures that bone tissue retains its resilience and mechanical strength.

Osteoblast Activation and Differentiation

- Magnesium acts as a cofactor for enzymes involved in collagen synthesis, providing the organic matrix upon which minerals deposit.

- It influences the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblast precursors, enhancing bone formation rates.

- Low magnesium levels impair osteoblast function, leading to reduced bone mass and compromised structural integrity.

Regulation of Parathyroid Hormone

- Magnesium regulates PTH release from the parathyroid glands; deficiencies can trigger hypoparathyroidism or resistance to PTH.

- Altered PTH dynamics affect calcium homeostasis, causing secondary bone loss and elevating fracture risk.

Dietary Sources, Absorption, and Bioavailability

Attaining adequate magnesium intake through diet is crucial for sustaining optimal bone health. Absorption occurs primarily in the small intestine via passive diffusion and active transport mechanisms. However, several factors influence bioavailability, including dietary composition, gastrointestinal health, and the presence of competing minerals.

Rich Food Sources

- Green leafy vegetables (e.g., spinach, kale)

- Whole grains (e.g., brown rice, oats)

- Nuts and seeds (e.g., almonds, pumpkin seeds)

- Legumes (e.g., black beans, chickpeas)

Factors Affecting Absorption

- High intake of dietary fiber or phytates can bind magnesium and reduce uptake.

- Excessive calcium or zinc supplementation may compete for absorption sites.

- Chronic gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., Crohn’s disease, celiac disease) impair transport mechanisms.

Role of Vitamin D and Hormonal Regulation

Vitamin D enhances intestinal absorption of magnesium and supports its incorporation into bone. Additionally, estrogens and thyroid hormones indirectly influence magnesium metabolism by modulating renal excretion and bone turnover rates. A balanced hormonal milieu is critical to maintain serum and skeletal magnesium levels within an optimal range.

Clinical Implications and Bone Disorders

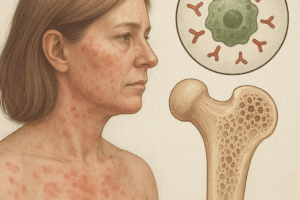

Emerging evidence links magnesium deficiency to a spectrum of bone disorders, including osteoporosis and increased susceptibility to fractures. Clinical studies demonstrate that individuals with low serum magnesium often present with lower bone mineral density (BMD) and exhibit accelerated bone loss during aging or postmenopausal transition.

Osteoporosis and Fracture Risk

- Magnesium deficiency disrupts bone remodeling cycles, promoting bone resorption over formation.

- It compromises the mechanical properties of bone tissue, increasing fragility.

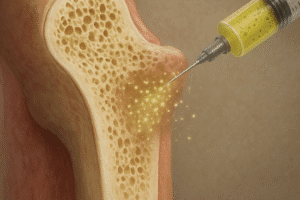

- Supplementation studies show improvements in BMD and reduced biomarkers of bone turnover.

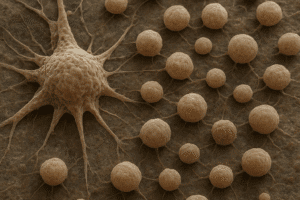

Inflammation and Bone Catabolism

Low magnesium status can enhance systemic inflammation by elevating proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn upregulate osteoclast activity. Chronic inflammation is associated with accelerated bone catabolism, highlighting the anti-inflammatory role of magnesium in preserving skeletal health.

Comorbid Conditions and Medication Interactions

- Diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome often correlate with suboptimal magnesium levels, exacerbating bone fragility.

- Proton pump inhibitors and diuretics may increase renal magnesium loss, necessitating monitoring in at-risk patients.

- Long-term corticosteroid therapy leads to magnesium depletion and heightened bone demineralization.

Synergistic Interactions with Other Nutrients

Bone health is maintained through a network of nutrient interactions, and magnesium synergizes with calcium, vitamin D, and vitamin K to optimize mineral deposition. While calcium provides bulk to the mineralized matrix, magnesium ensures proper crystal geometry and prevents overgrowth that can lead to brittleness. Vitamin D facilitates the absorption of both minerals, and vitamin K supports osteocalcin function, which binds calcium to the bone matrix.

Balancing Calcium and Magnesium

- Ideal dietary ratios range from 1:1 to 2:1 (calcium to magnesium) to ensure balanced uptake and function.

- Excessive calcium intake without adequate magnesium can lead to calcification of soft tissues and impaired bone quality.

Vitamin D Co-supplementation

- Vitamin D enhances intestinal transport of magnesium and supports its renal retention.

- Combined supplementation improves markers of bone formation more effectively than either nutrient alone.

Recommended Intake and Supplementation Strategies

Guidelines for magnesium intake vary by age, gender, and physiological status. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for adult men is approximately 400–420 mg/day, and for adult women 310–320 mg/day. Higher amounts may be required during pregnancy, lactation, or in the presence of certain medical conditions.

Supplementation Forms

- Magnesium citrate: high bioavailability, gentle on digestion.

- Magnesium oxide: lower absorption rate, often used for laxative effects.

- Magnesium glycinate: well-tolerated, reduces risk of gastrointestinal upset.

- Magnesium malate: beneficial for muscle function and energy production.

Safety Considerations and Tolerable Upper Intake Levels

Intakes above 350 mg/day from supplements may cause diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal cramping. Individuals with renal impairment should exercise caution, as excessive magnesium accumulation can lead to hypermagnesemia, characterized by muscle weakness, hypotension, and cardiac disturbances.

Monitoring and Clinical Assessment

- Serum magnesium is a poor indicator of total body stores; erythrocyte magnesium and ionized magnesium tests provide better insight.

- Bone density scans (DEXA) and markers of bone turnover help evaluate the impact of magnesium interventions on skeletal health.

- Regular dietary assessments and evaluation of gastrointestinal function are essential to identify malabsorption issues.