The integration of engineering principles with biological insights has revolutionized our understanding of bone strength. By exploring how physical forces interact with cellular activity, researchers can develop strategies to prevent fractures, design advanced implants, and improve rehabilitation protocols. This article delves into the biomechanical foundations of bone health, examines key influencing factors, surveys modern modeling techniques, and highlights clinical applications in medicine.

Understanding Mechanical Behavior of Bone

Bone Composition and Structure

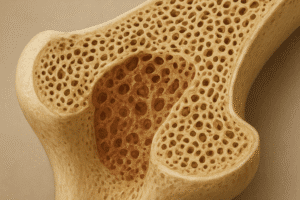

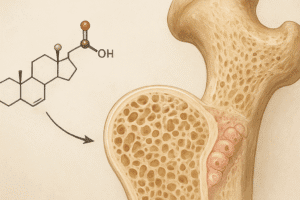

Bone tissue is a dynamic composite material consisting of an organic matrix of collagen fibers reinforced by hydroxyapatite crystals. This dual nature provides both flexibility and load-bearing capacity. The outer cortical bone (compact bone) offers high density and stiffness, while the inner trabecular bone (spongy bone) features a porous lattice that dissipates energy and distributes loads. The interplay between these two compartments determines overall skeletal resilience.

Mechanical Properties

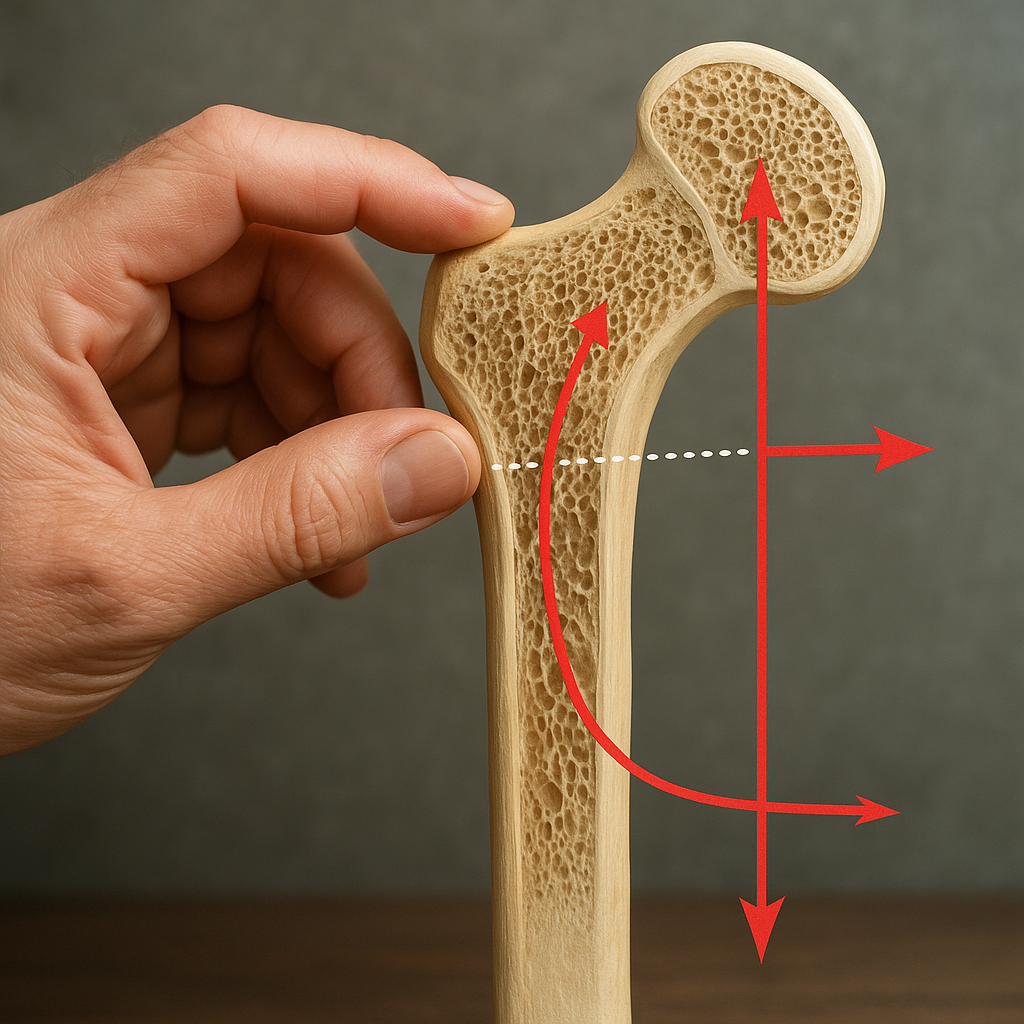

Key mechanical properties include stiffness, which governs resistance to deformation, and ultimate strength, the maximum stress a bone can withstand before failure. Under physiological conditions, bones are subjected to compressive, tensile, and shear forces that generate internal strain. Microstructural adaptations ensure that bones maintain integrity under repeated loading cycles. However, excessive or abnormal forces can exceed the material’s capacity, leading to fracture.

Influence of Biomechanical Factors on Bone Health

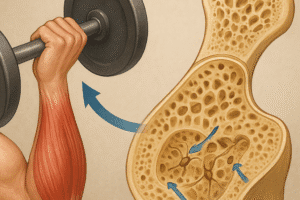

Mechanical Loading and Adaptive Remodeling

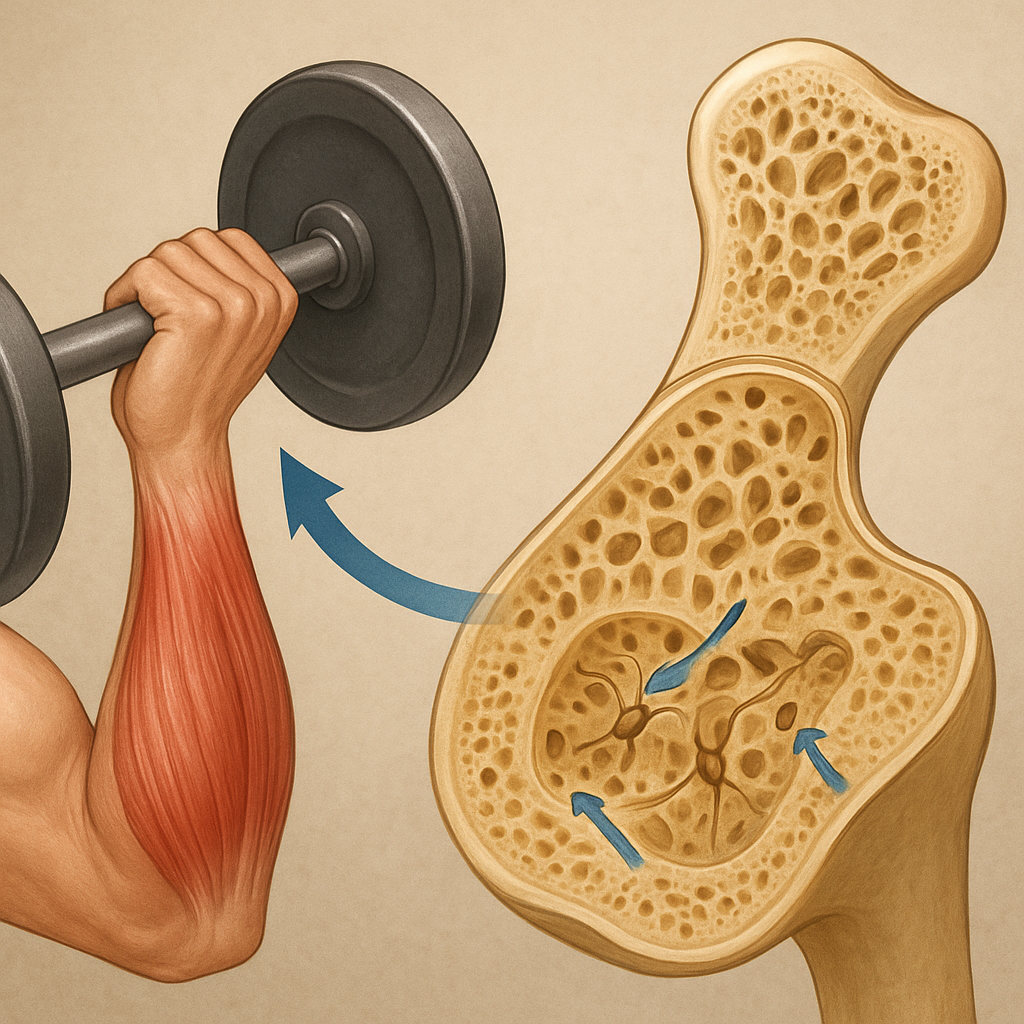

Bone tissue continually remodels in response to external forces, a phenomenon described by Wolff’s Law. Osteocytes detect changes in mechanical environment through mechanotransduction pathways and signal osteoblasts and osteoclasts to adjust bone mass and architecture. Adequate exercise, especially weight-bearing activities, promotes deposition of new bone through adaptive remodeling. Conversely, immobilization or microgravity environments can trigger rapid bone loss.

Role of Microarchitecture

The internal lattice of trabecular bone exhibits intricate geometry that maximizes strength while minimizing weight. Parameters such as trabecular thickness, spacing, and connectivity critically influence mechanical performance. Disruptions to the microarchitecture, whether through aging, disease, or disuse, significantly increase fracture risk. Recent imaging studies show that even small changes in trabecular orientation can reduce bone stiffness by up to 30%.

Modeling and Measurement Techniques

Finite Element Analysis

Computational approaches such as finite element analysis (FEA) allow for non-invasive simulation of stress distribution within complex bone geometries. High-resolution scans from CT or MRI are converted into 3D meshes where material properties are assigned based on density and orientation. FEA can predict weak points under specific loading scenarios and guide surgical planning or implant design.

Imaging Modalities and Biomechanical Testing

Advanced imaging techniques provide detailed insights into bone quality:

- Micro-CT imaging reveals trabecular connectivity and quantifies porosity.

- Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) estimates bone mineral density.

- Ultrasound assesses mechanical properties by measuring wave propagation speed.

Physical testing on cadaveric specimens complements imaging by applying controlled loads to measure failure points and characterize fracture mechanisms. Combined with FEA, these data enhance our understanding of how bones respond to real-world stresses.

Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Strategies

Osteoporosis Management

Osteoporosis is characterized by decreased bone mass and deterioration of microarchitecture, leading to heightened fracture risk. Biomechanical assessment can stratify patients based on predicted bone strength rather than solely density. Interventions include:

- Pharmacological agents that inhibit resorption or stimulate formation.

- Targeted exercise programs to enhance mechanical stimuli.

- Customized braces or orthopedic supports to redistribute loads.

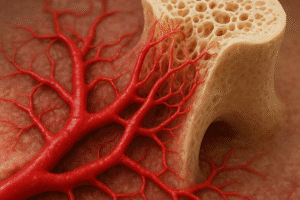

Design of Orthopedic Implants and Biomaterials

Successful implants must emulate native bone mechanics to avoid stress shielding and subsequent bone resorption. Advances in biomaterials and additive manufacturing enable production of porous scaffolds with tailored stiffness and surface properties that encourage osseointegration. Key considerations include:

- Matching the elastic modulus of surrounding bone.

- Creating pore architectures that support vascularization and cell migration.

- Incorporating bioactive coatings to facilitate bone in-growth.

Enhancing Rehabilitation

Postoperative rehabilitation protocols leverage biomechanical principles to optimize loading patterns that stimulate healing without overloading the repair site. Wearable sensors and motion-capture systems track patient progress, ensuring adaptive loading regimens accelerate recovery while minimizing complication risks.

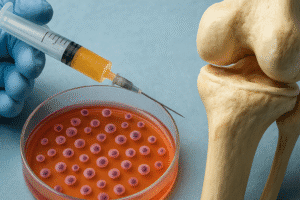

Future Directions in Bone Biomechanics

Emerging fields such as multiscale modeling integrate cellular biology with organ-level mechanics, offering unprecedented insights into how molecular changes manifest as macroscopic weaknesses. Innovations in bioengineering are paving the way for living bone grafts that combine scaffold mechanics with stem cell therapies. As technology evolves, personalized biomechanical profiles will become standard in preventive care, enabling early detection of skeletal fragility and customized interventions that preserve bone health across the lifespan.