Osteonecrosis, also known as avascular necrosis, represents a significant challenge in the field of bone and musculoskeletal medicine. This condition arises when the vascular supply to a segment of the bone is compromised, leading to cellular death and subsequent structural collapse. Individuals affected by osteonecrosis often experience progressive pain, reduced joint mobility, and, in advanced stages, joint destruction. Early recognition and timely intervention are therefore essential to preserve function and quality of life.

Causes and Risk Factors

At its core, osteonecrosis results from ischemia—the interruption of blood flow to bone tissue. Several mechanisms can precipitate this loss of perfusion:

- Corticosteroids: High-dose or prolonged use of steroids is one of the most common nontraumatic causes. Steroids can induce fat emboli and lipid deposition within marrow spaces, compressing blood vessels.

- Alcohol Abuse: Chronic heavy drinking promotes fatty deposits and interferes with normal bone cell metabolism, contributing to microvascular occlusion.

- Trauma: Fractures, dislocations, and joint injuries can directly damage blood vessels. For instance, displaced femoral neck fractures often compromise the main arterial supply to the femoral head.

- Blood Disorders: Conditions such as sickle cell anemia and thrombophilia increase the risk of infarctions by causing red cell sickling or hypercoagulability.

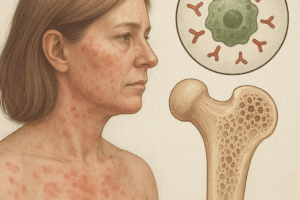

- Autoimmune Diseases: Systemic lupus erythematosus and other inflammatory disorders may require high steroid dosages and also induce vasculitis, further jeopardizing blood flow.

- Medical Treatments: Radiation therapy and bisphosphonate use (especially in oncologic indications) can disrupt normal bone remodeling and blood vessel integrity.

Additional risk factors include smoking, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic disorders like Gaucher disease. Genetic predispositions affecting coagulation pathways or lipid metabolism may also play a role, although these are still under investigation.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Osteonecrosis can progress through several stages, each with distinct clinical features:

- Pain: Initially, patients describe an aching discomfort localized to the affected joint. In early stages, the pain often appears only with weight-bearing or activity but later becomes constant.

- Reduced Range of Motion: Joint stiffness and a feeling of locking or catching may develop as the subchondral bone collapses.

- Gait Alteration: When weight-bearing joints such as the hip or knee are involved, limping or antalgic gait is common.

- Crepitus and Joint Effusion: In advanced cases, cartilage fragmentation leads to crepitus, swelling, and even audible clicks during movement.

Common sites of involvement include the femoral head (hip), knee (distal femur or proximal tibia), shoulder (humeral head), and less frequently the wrist or ankle. Bilateral disease occurs in up to 50% of cases, especially when systemic factors like steroid use are prominent.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Accurate diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical assessment, imaging studies, and sometimes histological confirmation:

Imaging Modalities

- X-Ray: Useful for detecting late-stage bone collapse, subchondral crescent signs, and joint space narrowing, but relatively insensitive in early disease.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The gold standard for early detection. MRI can reveal bone marrow edema, focal signal changes, and the “double line” sign indicating reactive interface between dead and reparative bone.

- Computed Tomography (CT): Provides detailed information regarding subchondral collapse and articular surface integrity, aiding in surgical planning.

- Bone Scintigraphy: Demonstrates decreased uptake in necrotic zones and can detect multifocal involvement but lacks the spatial resolution of MRI.

Laboratory and Histology

- Blood Tests: While no specific lab test confirms osteonecrosis, evaluation of lipid levels, coagulation profiles, and inflammatory markers may identify underlying etiologies.

- Bone Biopsy: Reserved for atypical cases or when ruling out infection and malignancy; reveals dead osteocytes within lacunae and marrow fat necrosis.

Early recognition through sensitive imaging allows for interventions aimed at halting progression before irreversible joint destruction.

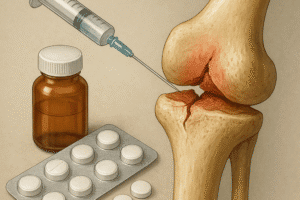

Treatment and Management Strategies

Therapeutic approaches depend on disease stage, lesion size, patient age, and comorbidities. A multi-disciplinary team often includes orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and physical therapists.

Non-Surgical Interventions

- Activity Modification: Reducing weight-bearing and avoiding high-impact sports to minimize further collapse.

- Pharmacotherapy:

- Bisphosphonates: May slow bone resorption and delay collapse.

- Anticoagulants: Used in cases linked to thrombophilia to improve microcirculation.

- Vasoactive Agents: Such as prostacyclin analogues, though evidence remains limited.

- Pain Management: NSAIDs or acetaminophen for analgesia; opioids reserved for refractory pain.

- Physical Therapy: Strengthening periarticular muscles and maintaining joint mobility to optimize function.

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT): Emerging modality with potential to stimulate angiogenesis and bone repair.

Surgical Options

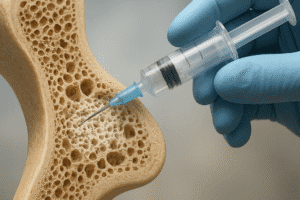

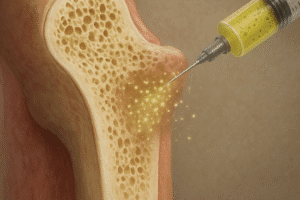

- Core Decompression: Drilling one or more channels into the necrotic zone to reduce intraosseous pressure and promote revascularization. Ideal for early-stage lesions.

- Bone Grafting: Incorporating vascularized or nonvascularized grafts to replace necrotic bone; often combined with core decompression.

- Osteotomy: Realignment procedures to shift weight-bearing away from necrotic regions, prolonging joint survival.

- Total Joint Arthroplasty: Indicated for end-stage collapse with severe pain and loss of function. Hip and knee replacements yield excellent outcomes in appropriately selected patients.

Emerging Therapies and Research Directions

Innovations in cell-based and biologic treatments hold promise for osteonecrosis management:

- Stem Cell Therapy: Autologous bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells introduced into the necrotic lesion aim to enhance angiogenesis and osteogenesis.

- Growth Factors: Recombinant proteins like bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) to stimulate bone repair.

- Gene Therapy: Experimental approaches to upregulate pro-angiogenic factors within ischemic bone.

- 3D-Printed Scaffolds: Customized implants seeded with cells and growth factors, designed to replace necrotic segments and promote regeneration.

Ongoing clinical trials are investigating the efficacy and safety of these novel modalities, potentially shifting the treatment paradigm from reactive to regenerative strategies.