Introduction

Global demand for orthopedic implants continues to climb. For example, over seven million joint replacement surgeries are performed each year in the United States alone, and similar trends are seen worldwide. This growing need has driven a booming medical device industry and strong research efforts to improve implant technology. As people live longer and stay active, clinicians and patients expect implants to last longer and perform more naturally. In response, engineers and doctors are developing advanced implant solutions that restore mobility, reduce pain, and enhance quality of life. These include innovative materials, patient-specific designs, and smart implants. Together, these approaches address persistent problems such as implant loosening, infection, and biocompatibility. This guide explores the latest breakthroughs and emerging trends in orthopedic implant technology.

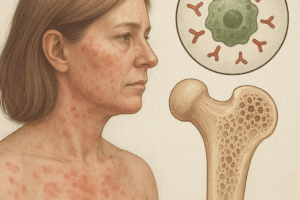

Advanced Biomaterials for Implants

Modern orthopedic devices rely on a variety of sophisticated biomaterials that combine strength, durability, and biocompatibility. Traditional implant materials like titanium alloys, cobalt-chromium, and stainless steel have dominated the field for decades due to their mechanical strength. However, researchers are introducing new materials and composites to overcome their limitations.

Metallic Alloys and Composites

Titanium and its alloys remain the cornerstone for load-bearing implants. Newer titanium grades and surface treatments enhance corrosion resistance and strength. Beta-titanium alloys, for example, eliminate potentially toxic elements like aluminum while retaining titanium’s favorable weight-to-strength ratio. Other metals such as tantalum and niobium have also gained attention. Porous tantalum, known for its sponge-like structure, closely mimics natural bone. Implants made from tantalum (often called “trabecular metal”) encourage bone in-growth and have shown outstanding stability in hip and knee reconstructions. Stainless steel (such as 316L) is another commonly used metal, valued for its low cost and high strength. Stainless steel is widely employed in trauma plates, screws, and external fixators. Cobalt-chromium alloys, on the other hand, provide extreme hardness and wear resistance. They are often used for articulating surfaces in joint implants or large tumor prostheses. However, metal ions (such as cobalt or chromium) can sometimes cause tissue reactions, which motivates the development of improved alloys.

Nickel-titanium, or Nitinol, is a remarkable metal alloy with shape-memory and superelastic properties. Nitinol can deform under force and then spring back to its original shape, making it useful for specialty devices. For instance, Nitinol-based staples and stents have been explored for pediatric fractures and spinal applications, as they can adapt to changing loads. These flexible implants may one day allow bones to grow under tension or provide dynamic stabilization in the spine. Research continues to find new alloy compositions (including magnesium- or iron-based alloys) that balance mechanical performance with biocompatibility.

Composite materials, which combine metals with other substances, are also emerging. By embedding ceramic particles or fibers into a metal matrix, engineers can tailor properties like stiffness and toughness. For example, carbon-fiber-reinforced titanium is being developed for fracture fixation: the carbon adds stiffness matching bone while the titanium provides strength. Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (like CFR-PEEK) are another class of composites gaining traction. CFR-PEEK implants have a stiffness much closer to that of bone than metal does, which can reduce stress shielding. These composites are also radiolucent (transparent on X-rays) and do not generate MRI artifacts, advantages in post-operative imaging. In summary, metallic alloys are evolving to achieve higher strength, lower weight, and better bone integration through novel compositions and composite designs.

Polymers and Ceramics

High-performance polymers play a growing role in modern implants. Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) are two of the most important polymer materials. These plastics are used in applications where metal is not ideal. PEEK is radiolucent and has an elastic modulus closer to bone, making it useful in spinal implants and interbody fusion cages. UHMWPE is widely used as a bearing surface in hip and knee replacements. Early versions of UHMWPE wore out relatively quickly, but advancements such as highly cross-linking and Vitamin E stabilization have dramatically improved its wear resistance. Modern UHMWPE liners generate much fewer wear particles, extending the life of joint replacements. Researchers are also exploring polymer additives: for instance, mixing ceramic or carbon particles into PEEK can further increase its strength. Additionally, some implants use bioresorbable polymers (discussed later) so that devices like screws and pins can dissolve after healing.

Bioceramics offer another important class of materials. Alumina and zirconia ceramics are exceptionally hard and wear-resistant. Third-generation ceramic alloys are now used for joint surfaces (such as femoral heads or acetabular inserts) that can endure millions of cycles with minimal wear. Ceramics do not corrode or rust, and their smooth surfaces can reduce friction. Calcium-phosphate ceramics, such as hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphate, are bioactive. These materials chemically resemble bone mineral. When coated on an implant, they encourage bone cells to attach and grow, promoting osseointegration (the process of bone bonding directly to the implant). Many titanium implants are coated with a thin layer of hydroxyapatite to achieve this. Bioactive glass coatings are also under investigation, as they can release ions that further stimulate bone healing. In all, the combination of polymers and ceramics is creating implants that are lighter, more bone-friendly, and longer-lasting than ever before.

Nanotechnology in Implant Materials

Nanotechnology is revolutionizing how implants interact with the body. Engineers can now control material features at the nanometer scale, where many biological processes occur. For example, titanium surfaces can be modified with nanostructures such as nanotube arrays or nanopillars. These tiny patterns increase surface area and improve protein adsorption. As a result, bone-forming cells (osteoblasts) find it easier to attach, spread, and lay down new bone matrix on the implant. Many studies have shown that nanoscale roughness greatly enhances the speed and strength of bone integration.

New nanoparticles and nanofibers are being added to implant coatings and cements. Nano-additives in coatings can slowly release drugs or growth factors right at the implant surface. Researchers have loaded hydroxyapatite with nanoscale antibiotic carriers or growth proteins. As the coating dissolves, it can deliver these substances to nearby cells in a controlled way. Similarly, nanoparticles of silver or copper can be dispersed in a coating to provide long-lasting antibacterial action (detailed in a later section).

At the material level, nano-composites are also under development. For instance, carbon nanotubes and graphene are used to create ultra-strong, lightweight implant materials. Adding graphene oxide to a polymer like PEEK can greatly increase its mechanical strength and electrical conductivity. Nanofibrous scaffolds, made via electrospinning or 3D printing, mimic the natural collagen matrix of bone and cartilage. These scaffolds allow cells to infiltrate and deposit new tissue. Overall, nanotechnology enables orthopedic implants to interact with the body at a cellular level, enhancing integration, promoting regeneration, and preventing complications in ways that were not possible a decade ago.

Surface Engineering and Bioactive Coatings

While the bulk material of an implant is important, the surface that contacts the body is equally crucial. Surface engineering focuses on modifying implant surfaces to improve integration and function. One long-standing approach is to create porous and textured surfaces. A porous metal surface provides a scaffold into which bone can grow. Pore sizes on the order of 100–500 micrometers allow bone cells and blood vessels to penetrate, locking the implant in place. Modern implants often use techniques like 3D printing, plasma spraying, or acid etching to achieve this. For example, some hip stems and acetabular cups now have a 3D-printed trabecular metal structure that resembles cancellous bone. These porous surfaces can achieve stable fixation without the need for cement, especially in patients with good bone quality. Textured surfaces (roughened by blasting or machining) also improve initial mechanical grip, reducing micromotion until biological bonding occurs. In short, porous and textured surfaces greatly accelerate osseointegration and reduce the risk of loosening.

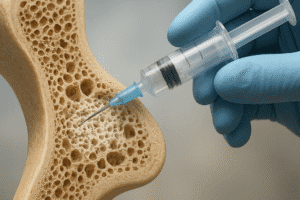

Another key strategy is bioactive and osteoconductive coatings. These coatings make an implant chemically active, so it can bond with bone. Hydroxyapatite (HA) is the classic example. HA is a calcium phosphate mineral similar to natural bone mineral. When HA is coated on a metal implant, it provides a friendly surface for bone. Cells migrating to the interface will see HA as “bone-like” and begin laying down new matrix that chemically bonds to the coating. This process significantly speeds up bone healing around the implant. Some implants are also coated with bone-growth proteins (such as BMPs) embedded in a biodegradable layer. Other materials like bioactive glass or certain calcium phosphate mixtures can also serve as coatings. These treatments aim to move beyond passive implants to surfaces that actively encourage bone formation and remodeling. By promoting osseointegration, bioactive coatings ensure that the implant becomes part of the living skeleton, improving long-term stability.

One of the toughest challenges in orthopedics is preventing infection. Once bacteria land on an implant and form a protective biofilm, conventional antibiotics have difficulty reaching them. To address this, engineers are developing antibacterial and anti-infection surface technologies. One approach is to coat the implant with bacteria-killing agents. For example, silver nanoparticle coatings release silver ions that are toxic to many microbes. Studies in animals have shown that silver-coated implants dramatically lower infection rates. Another strategy is to apply antibiotic-loaded coatings. A commercial example is an intramedullary nail coated with gentamicin (an antibiotic); clinical trials showed that infection rates dropped from around 18% with an uncoated nail to just 3% with the antibiotic coating. More recently, novel coatings have been developed that kill bacteria on contact without releasing drugs. One such coating uses immobilized quaternary ammonium molecules that rupture bacterial cell walls when they touch the surface. This technology has even gained regulatory approval for use in high-risk joint revision surgery. In the lab, researchers are also experimenting with “smart” coatings that respond to infection cues. For instance, some coatings remain inert until low pH (produced by bacteria) triggers a burst release of antibiotic. Others embed antimicrobial peptides or enzymes that can disperse biofilms. These multifaceted surface treatments aim to keep the implant sterile during the critical healing period. Combined with strict surgical protocols, antibacterial surfaces are transforming implants from inert objects into active defenders against infection.

Additive Manufacturing and Custom Implant Design

Additive manufacturing (AM), commonly known as 3D printing, has opened a new frontier in orthopedic implant design. Unlike traditional machining, 3D printing builds parts layer by layer from a digital model. This process gives engineers unprecedented freedom to create complex and patient-specific geometries. A major advantage is patient-specific implants. Using CT or MRI scans of a patient’s bone, a surgeon can work with engineers to design an implant that fits the exact contours of the defect. For example, if a cancerous tumor is removed from the pelvis, a custom titanium implant can be printed to fill that exact void. Hospitals have already implanted patient-specific 3D-printed titanium cups for patients with massive acetabular bone loss. These tailored implants avoid the compromises and gaps of off-the-shelf components. They can shorten surgery time and improve biomechanical alignment since no extra bone removal is needed to fit a generic shape. In short, patient-specific 3D-printed implants adapt to the patient, not the other way around.

Beyond just matching the outer shape, additive manufacturing also allows designing an implant’s internal architecture. Engineers can build lattices, honeycombs, and other porous networks directly into the metal. These internal pores serve many purposes. First, they dramatically reduce stiffness. A solid titanium plate has a stiffness far higher than bone, which can cause stress shielding (bone weakening). But a lattice-filled plate can match the stiffness of bone more closely, transferring load to the skeleton and preventing bone loss. Second, the pores provide space for bone to grow through the implant, creating a true bone-implant scaffold. Surgeons can use porous titanium cages in spinal fusions; bone fusion plugs right through the print and solidifies in 3D space. Third, varying pore size and shape can be customized in different regions of an implant. For example, a hip stem might have a gradient of porosity: dense where support is needed, but porous near the bone-implant interface. These complex internal designs were impossible with older manufacturing.

Various additive manufacturing methods are used in orthopedics. Powder-bed fusion techniques (laser or electron-beam melting) are common for metal implants like titanium and cobalt alloys. Polymer parts (e.g., PEEK) can be made with extrusion or selective printing. Excitingly, researchers are even exploring bioprinting, where living cells and bioactive materials are printed together. Early experiments have produced bone-like grafts containing the patient’s own cells. In the future, one could imagine printing a bone scaffold seeded with stem cells in the operating room. While clinical use of bioprinted tissues is still years away, the potential is enormous.

Of course, 3D printing in medicine also brings new challenges. Each printed implant must meet strict quality standards. The printing process can introduce internal defects or inconsistent microstructures. Implants must be thoroughly tested for fatigue and toughness. Regulatory bodies are still adapting to this technology. Unlike mass-produced implants, a custom 3D part may require individual certification. Hospitals and manufacturers are working on guidelines and protocols to ensure the safety and repeatability of 3D-printed implants. Despite these hurdles, the ability to print complex and patient-matched implants continues to revolutionize the field, enabling implants that fit better, feel more natural, and allow bone to heal more effectively.

Smart Orthopedic Implants

The term “smart implants” refers to devices that incorporate sensors, electronics, or active features to gather information or interact with the body. This is an emerging trend that could transform orthopedic care from static replacement to dynamic monitoring.

Sensor-Integrated Prostheses

One approach is to embed miniature sensors into the implant itself. Modern microelectronics have become so small and energy-efficient that they can be integrated into joint replacements or fixation plates. For example, researchers have created knee replacement prototypes with pressure sensors built into the tibial (shinbone) component. These sensors measure the load distribution in real time as the patient walks. The data can be sent wirelessly to a computer or even a smartphone. Surgeons could use this information to optimize the alignment and balance of the joint during surgery. After surgery, patients and doctors could track how the knee is loading during activities. Abnormal force patterns might indicate uneven wear or soft tissue issues before they become painful problems. Similarly, spinal implants with embedded accelerometers or strain gauges can monitor spine motion and fusion status. A fracture plate with a tiny wireless thermometer could detect early fever indicating infection at the surgical site. The key idea is turning passive implants into data collectors that provide objective feedback.

Data-Driven Orthopedic Care

The data from smart implants could have broad implications. Imagine a world where each implant is part of a larger Internet of Medical Things. Machine learning algorithms could analyze gait and load data from hundreds or thousands of patients to identify patterns. For example, if certain knee flexion patterns predict implant wear, doctors could intervene earlier. Patients could have smartphone apps that display implant performance metrics. If a hip replacement implant sensed excessive impact loading during running, it could alert the patient to limit high-impact activities. Surgeons could also receive postoperative analytics: for instance, a shoulder implant could signal that the patient is consistently compensating in a way that risks loosening. This data-driven approach shifts some care from reactive to proactive. Instead of waiting for symptoms, clinicians may one day use implant-generated data to guide rehab exercises, adjust medication, or plan early interventions.

Active and Therapeutic Implants

Beyond sensing, some future implants may have active therapeutic functions. Researchers are experimenting with electrically stimulating implants. Tiny electrodes embedded in an implant could deliver small electrical pulses to bone tissue, promoting healing and fusion. Early-stage studies show that electrical stimulation can enhance bone cell activity. An implant could even be battery-powered or harvest energy from body movement to power itself. Another concept is drug-eluting implants. Imagine a spinal fusion cage or trauma screw that contains a microscopic drug reservoir. If a surgeon detects a patient at high risk of infection, the implant could release antibiotics over the first critical weeks. Once healing is underway, the release could stop. Similarly, implants could release growth factors to accelerate tissue regeneration. These active features blur the line between hardware and therapy, aiming to create implants that do more than just provide mechanical support.

Biodegradable and Bioabsorbable Implants

A major area of innovation is biodegradable implants that do their job then disappear, avoiding a second surgery to remove hardware. These temporary implants are especially attractive in pediatric orthopedics and certain fractures.

Polymer-Based Bioabsorbables

The earliest bioabsorbable implants were made of polymers. Materials like polylactic acid (PLA) and polyglycolic acid (PGA) have long been used for sutures and mesh implants. In orthopedics, PLA/PGA screws, pins, and tacks were introduced decades ago. These devices slowly degrade by hydrolysis into carbon dioxide and water, which the body can safely eliminate. The big advantage is clear: once the bone has healed, there is no permanent hardware left to irritate tissue or require removal. Another advantage is gradual load transfer. As the implant weakens, more load is carried by the healing bone, potentially improving remodeling and preventing stress shielding. Surgeons have used polymer implants in pediatric fractures, certain ankle and wrist injuries, and hallux (big toe) procedures where a second surgery would be burdensome.

However, early polymer implants also had drawbacks. They are generally weaker than metal, so they cannot bear high loads for long. A more significant issue has been unpredictable degradation. In some patients, the polymer remains intact for many months with little effect, and then suddenly breaks down in a “burst release.” During that rapid degradation, acidic by-products are released, which can trigger intense inflammation and pain around the implant. In worst cases, it has led to foreign-body reactions or necessitated early removal. Manufacturers have worked to improve polymer formulations and manufacturing techniques. Copolymers (mixing PLA and PGA, for example) can moderate the degradation rate. Even so, the limitations of polymers have driven the search for better solutions.

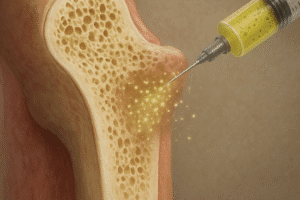

Biodegradable Metal Implants

In recent years, a very promising development is the use of biodegradable metals, primarily magnesium-based alloys. Magnesium is a normal mineral in bone and the body, and it has several attractive properties as an implant material. Pure magnesium has a strength comparable to some titanium alloys, but its elastic modulus is closer to bone (around 40-45 GPa versus 110 GPa for titanium). This reduces stress shielding compared to titanium devices. Perhaps more importantly, magnesium corrodes in the body in a controllable way. As it corrodes, it slowly releases magnesium ions (which are harmless and may even stimulate new bone formation) and creates tiny pores where bone can grow. Several companies have brought magnesium screws and pins into clinical trials. Early results have been encouraging: in certain foot and wrist fractures, magnesium screws held the bones together adequately and then gradually dissolved over 6–12 months. X-rays showed the screws fading away as new bone took their place. Patients avoided a second operation to remove hardware, and follow-up imaging revealed healthy bone healing.

Magnesium implants are not without challenges, however. Magnesium corrodes rather quickly, and hydrogen gas is a byproduct. If corrosion happens too fast, it can compromise mechanical support prematurely and cause gas pockets in tissue. To manage this, alloying and surface coatings are used. Adding small amounts of rare earth metals or aluminum can slow corrosion and strengthen the alloy. Surface coatings (for example, thin ceramic layers) can control the initial corrosion rate. Researchers are also exploring other bioresorbable metals. Zinc-based alloys degrade more slowly than magnesium (zinc is an essential mineral in enzymes), so they may suit applications that require medium-term support. Iron-based alloys corrode very slowly and tend to rust, so scientists are formulating iron-manganese alloys and porous structures to speed the degradation to a useful rate. The goal is to tune the degradation profile so that the implant stays strong while healing is incomplete, then completely dissolves once its job is done.

Resorbable Scaffolds and Composites

Beyond monolithic implants, many bioabsorbable devices are coming as scaffolds or composite materials. In bone void filling and spine fusion, surgeons use resorbable cements and scaffolds that gradually get replaced by bone. One example is calcium phosphate cement, which sets like bone cement but slowly dissolves to release calcium and phosphate ions. When combined with a biodegradable polymer or collagen matrix, such composites form a scaffold that supports load initially but vanishes over time. The porous structure is key: it allows blood vessels and new bone tissue to infiltrate from all sides. Bioactive glass ceramic blocks are another resorbable option: they bond to bone and then slowly dissolve while stimulating new bone growth. Even novel polymers and silk-based materials are under study for ligament and tendon repair, providing temporary support and turning into harmless degradation products. These resorbable scaffolds aim to mimic natural healing processes. They can be impregnated with drugs or growth factors and designed with intricate porosity to optimize tissue regeneration. In the future, it is conceivable that a surgeon could implant a degradable scaffold that is precisely shaped (even 3D-printed) for the patient’s anatomy and cell-seeded to accelerate recovery. Once the biological repair is complete, the entire construct disappears, leaving only natural tissue behind.

Robotic-Assisted Surgery and AI in Orthopedic Implants

Advances in implant technology are paralleled by advances in surgical techniques. Robotic-assisted and computer-assisted systems are increasingly used to place implants with greater precision. Robots like MAKO for hip and knee replacement, or ROSA for knee and spine procedures, guide the surgeon’s instruments along a preoperative plan. These systems provide millimeter-level accuracy and consistency. In practice, a robot arm will hold a saw or drill and remove bone according to the planned cuts, reducing small errors that can occur with hand-held tools. As a result, implants can be aligned within very tight tolerances. Early studies show that robot-guided surgeries have fewer outliers in component positioning compared to traditional methods. Improved alignment and fit may translate to more natural joint kinematics, less wear, and potentially better long-term outcomes. Robotics also facilitate minimally invasive approaches: because the robot can execute fine movements through small incisions with image guidance, patients often have smaller scars, less blood loss, and faster early recovery.

Augmented reality (AR) is another emerging tool in the operating room. AR headsets allow the surgeon to see a virtual overlay of the patient’s anatomy and surgical plan on the actual surgical field. For example, while looking at the hip socket, the surgeon might see a ghost image of the optimal cup position and alignment lines. This technology can be used alongside robotics: the robot may display its planned cuts on the AR view as it works. In essence, AR transforms surgical navigation from indirect imaging into a direct visual guide. It promises to make implant insertion both more automated and more customized to each patient. The combination of robotics, AR, and advanced navigation systems means that even complex anatomies can be reconstructed with confidence and speed. In the future, we may also see artificial intelligence (AI) play a larger role. For instance, machine learning algorithms could analyze preoperative images to suggest optimal implant size and position, or real-time feedback algorithms could adjust robotic movements based on sensor input. These digital innovations are enhancing surgeon skill and consistency. While they are not implants themselves, they are a critical part of ensuring that the cutting-edge implants work exactly as intended inside the body.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The pace of innovation in orthopedic implants shows no signs of slowing. Researchers are exploring bioinspired and regenerative approaches that blur the line between synthetic implants and living tissue. One exciting area is tissue-engineered implants. Scientists are experimenting with scaffolds seeded with stem cells or biochemical cues, hoping to regenerate bone and cartilage rather than just replace it. For example, a future implant might be embedded with the patient’s own stem cells or growth factors so that it actively builds new tissue. Smart materials are also under investigation. These are materials that can change properties in response to the environment. Imagine a metallic implant that senses stress and becomes slightly more rigid under higher loads, or a polymer that delivers electrical stimulation when it bends. Self-healing materials are another futuristic idea, where microscopic capsules of adhesive or cement release to repair tiny cracks before failure.

The digital transformation of orthopedics will continue. Implants of the future may be linked to databases via wireless technology. Surgeons could monitor implant performance remotely and even receive alerts if an implant is overused or reaching fatigue limits. 3D printing is also expected to become even faster and more versatile, potentially allowing hospitals to fabricate patient-specific implants on-site when needed. Artificial intelligence will likely be used in implant design; for example, generative design algorithms might create novel lattice structures that a human would not conceive but that perfectly optimize strength and weight.

Sustainability and patient empowerment are emerging as considerations too. Researchers are looking at more environmentally friendly manufacturing methods and the recyclability of implant materials. Patients will also have more access to information. Digital platforms and mobile apps could help individuals understand their implant, the expected recovery timeline, and how to best rehabilitate. Education and engagement are powerful new tools in ensuring implant success.

In summary, the field of orthopedic implants is entering an era of remarkable personalization and interactivity. New biomaterials, surface technologies, manufacturing processes, and digital tools are coming together. Future implants will do more than simply “act as a joint” — they will integrate with the patient’s body and healthcare system. Implants may actively guide healing, monitor themselves, and adapt to each patient’s needs. For patients and clinicians, these advances promise implants that fit better, recover faster, and perform more naturally than ever before. Each year brings new discoveries, and the comprehensive guide presented here highlights how innovation continues to push the boundaries of what orthopedic implants can achieve.