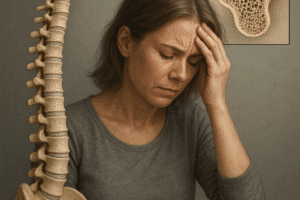

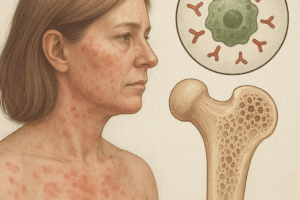

Healthy bones depend on more than just luck – they rely on a rich supply of nutrients. A balanced diet packed with vitamins, minerals, and protein is essential for strong skeletal health. In fact, osteoporosis and low bone mass are widespread: roughly 10 million Americans over age 50 have osteoporosis and 34 million have low bone density. Many suffer fractures that could be prevented by proper nutrition and lifestyle. For example, studies emphasize that good eating habits combined with regular exercise are crucial to maintaining bone strength and preventing breaks. Building and preserving bone is a lifelong process. Around age 30 (25 for women, 30 for men) we reach peak bone mass, after which bone density gradually declines. Therefore, eating a variety of nutrient-rich foods from childhood onward helps maximize bone growth and delay age-related loss.

Key Nutrients for Strong Bones

Bones are living tissue made of minerals and protein. Certain nutrients play especially important roles:

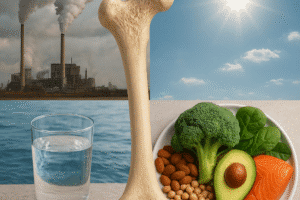

- Calcium – the main mineral in bone – is the building block of the skeleton. Adequate calcium intake “can significantly reduce the loss of bone” over time. The richest sources are dairy foods (milk, yogurt, cheese) and calcium-fortified foods, but green leafy vegetables (e.g. broccoli, collard greens), almonds, beans and seafood also provide substantial calcium. For example, one cup of milk or yogurt supplies roughly 25–30% of the daily calcium need (about 290–320 mg), and dairy products often come fortified with vitamin D.

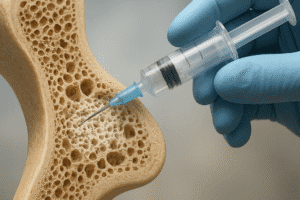

- Vitamin D – often called the “sunshine vitamin” – is critical because it enables the body to absorb calcium efficiently. Without enough vitamin D, even a high-calcium diet can’t build strong bone. When vitamin D levels fall, calcium absorption drops and the hormone PTH rises, triggering bone breakdown (osteolysis) to release calcium into the blood. Good dietary sources include fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, sardines), egg yolks, fortified dairy or plant milks, and supplements. Spending 10–20 minutes in the sun each day can also boost vitamin D. Research shows that giving calcium together with vitamin D supplements significantly lowers bone loss and fracture risk in older adults.

- Magnesium – a less famous mineral – is also essential for bone health. Magnesium helps form bone crystals and influences hormones that regulate bone turnover. It “improves bone quality” by contributing to the architecture of bone matrix. In fact, many people do not get enough magnesium from diet, as noted by experts who list magnesium among nutrients that are frequently insufficient. Good sources include nuts (almonds, cashews), whole grains, legumes and leafy greens.

- Vitamin K – found in leafy greens (kale, spinach, broccoli) and fermented foods – is required for proteins that bind calcium in bone. Low vitamin K levels have been linked with reduced bone density and higher fracture risk. Including greens and foods like prunes (dried plums) can help. Prunes are high in vitamin K and potassium, and studies suggest they may improve bone density and lower fracture risk.

- Vitamin C – abundant in citrus fruits, berries, peppers and leafy vegetables – is critical for collagen production. Bone’s organic matrix is largely collagen, a strong fibrous protein. Adequate vitamin C ensures that collagen scaffolding in bone is properly formed. Increased intake of vitamin C (through diet or supplements) has been associated with higher bone density in humans. In other words, vitamin C helps “cement” the bone structure.

- Protein and amino acids – bone is about 30% protein by dry weight, mostly collagen. A diet providing enough high-quality protein is needed for bone growth and repair. Collagen formation requires amino acids like lysine and proline, along with vitamin C. Inadequate protein intake can limit bone development, while too much protein (especially animal protein) can increase calcium excretion unless calcium intake is also high. In moderation, protein supports bone mass, but it’s best balanced by ample calcium and fruits/vegetables to offset any acid load.

- Other Minerals – Several trace elements contribute to bone strength. For instance, zinc, copper and manganese are cofactors for enzymes that build bone matrix. Boron and silicon (found in some plant foods) also support bone formation. Doctors note that diets often fall short on magnesium, silicon, vitamin K and boron – and that each is an “important contributor to bone health”. While deficiencies in these trace nutrients are common, be careful with supplements: excessive zinc or copper can be harmful. A varied diet with fruits, vegetables, nuts and whole grains usually covers these micronutrients.

- Fats – Healthy fats, especially omega-3 fatty acids from fish or flaxseed, may benefit bones by reducing inflammation. Fatty fish like salmon and sardines are rich in omega-3s and vitamin D. Diets very high in saturated fat or extreme high-fat eating have been linked to poorer bone density and higher fracture risk. In contrast, some evidence suggests unsaturated fats like those in olive oil might be neutral or slightly protective for bone. For example, olive oil’s vitamin E content could explain why Mediterranean-style diets often correlate with better bone metrics. In any case, aim for moderate fat intake with an emphasis on sources like nuts, seeds, avocados and oily fish.

Bone-Boosting Foods and Diets

A nutrient-packed diet is the best way to deliver bone-healthy vitamins and minerals. Focus on these food groups:

- Dairy and Fortified Foods – Milk, yogurt and cheese are classic calcium sources. One serving of milk (about 8 ounces) provides roughly 290 mg of calcium. Many dairy products today are fortified with vitamin D as well, making them a one-two punch. If you are vegan or lactose-intolerant, choose calcium-fortified alternatives: some orange juices, plant milks (soy, almond, oat) and cereals are enriched with calcium and vitamin D. For example, a cup of fortified soy milk can offer as much calcium as a cup of cow’s milk.

- Leafy Green Vegetables – Greens like kale, collard greens, bok choy, turnip greens and mustard greens are excellent for bone. A cup of cooked collard greens or kale can supply about 25% of daily calcium needs. These vegetables also contain magnesium, vitamin K and potassium – nutrients linked to higher bone density. (Note: Although raw spinach is high in calcium, its oxalates bind calcium and reduce absorption. Still, cooked greens and cruciferous veggies are great.) Aim to fill half your plate with colorful vegetables to tap their bone-friendly mix of nutrients.

- Fruits – Many fruits contribute to bone health. Oranges and berries provide vitamin C, which aids collagen formation. Bananas, oranges, and potatoes (yes, potatoes) supply potassium, helping to neutralize bone-leeching acids. Prunes stand out: research suggests eating about 5–6 prunes a day can improve bone density in postmenopausal women, thanks to their vitamin K, potassium and antioxidant content. Apples, grapes and citrus, while not high in calcium, are alkalizing and support an overall bone-friendly diet.

- Legumes and Nuts – Beans (black beans, kidney beans, chickpeas) offer calcium, magnesium, zinc and protein. They also contain phytates, which can slightly inhibit calcium absorption – soaking or cooking beans well can minimize that effect. Nuts like almonds and walnuts are bone-friendly too. Almonds have more calcium than other nuts and also provide magnesium. In fact, almonds supply essential bone nutrients (calcium, magnesium, protein) in a single snack. Other nuts like brazil nuts (selenium) and pistachios (potassium) can be included in moderation.

- Soy Products – Tofu made with calcium sulfate can be very calcium-rich (half a cup might give 85% of RDI). Soybeans and edamame contain isoflavones – plant compounds that mimic estrogen’s bone-sparing effects – and can slow bone loss, especially in postmenopausal women. Fermented soy (natto) is a very good source of vitamin K2, which activates bone-building proteins. Including tofu, tempeh or soy milk in your diet adds both protein and bone-supporting nutrients.

- Fish and Seafood – Fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, sardines and tuna are rich in vitamin D and omega-3 fats. Canned salmon and sardines (with bones) are also loaded with calcium – a single can of sardines provides about 35% of the daily calcium requirement. Omega-3s in fish help reduce inflammation and may slow bone resorption. Even shellfish like oysters and shrimp offer trace minerals (zinc, copper) that support bone enzymes. Try to eat fatty fish at least twice per week for bone health.

- Lean Proteins – Skinless poultry, lean beef, eggs and fish supply high-quality protein needed for bone matrix. These foods also provide phosphorus (in balance with calcium), B vitamins and other nutrients. However, very high-meat diets can increase calcium loss, so balance meat servings with ample calcium sources. Plant proteins (beans, lentils, tofu, tempeh) are excellent too and tend to be lower in acid load. If you follow a high-protein diet for muscle or weight reasons, be sure to also drink milk or eat cheese to offset the protein’s impact on calcium balance.

- Healthy Oils and Antioxidant Foods – Cooking with olive or flaxseed oil adds vitamin E and omega-3s. Research hints that diets rich in antioxidants (berries, leafy greens, nuts) are protective for bone by reducing oxidative stress. Foods like blueberries, tomatoes, garlic and onions provide bioactive compounds that may indirectly support bone remodeling. While the evidence is still emerging, a diet rich in variety of whole foods (the Mediterranean diet being a good example) is generally associated with better bone health than a diet high in processed foods.

Patterns and Pitfalls: What to Limit

Not all diets support bone strength. Certain eating patterns can undermine bone health:

- High Salt and Processed Foods – A diet very high in sodium causes calcium to be excreted in urine. Frequent intake of salty snacks, canned foods and table salt has been shown to increase calcium loss and bone loss. For example, a processed food diet can hasten bone thinning, especially if calcium intake is marginal. To protect bones, aim to keep sodium under 2300 mg/day (preferably much less) by choosing fresh foods, seasoning with herbs instead of salt, and checking labels.

- Sugary Beverages and Refined Carbohydrates – Excess sugar can negatively affect bone. Studies show that children and adolescents who drink a lot of soda or sugar-sweetened beverages tend to have lower bone mineral content. The sugar and phosphoric acid in soda may interfere with calcium balance. Even in adults, high soft drink consumption correlates with reduced bone density, especially in women. Choose water or milk instead of soda, and limit sweets that displace healthier foods.

- Oxalates and Phytates – Some healthy foods contain compounds that bind calcium. Spinach, rhubarb, beet greens and Swiss chard are high in oxalic acid, which blocks most calcium absorption. Similarly, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds contain phytic acid that can inhibit mineral uptake. This doesn’t mean these foods are “bad” – they are nutritious in many ways – but don’t rely on them as your sole source of calcium. For instance, don’t count raw spinach as a calcium source. If eating high-oxalate foods, pair them with a dairy or fortified food so your body gets absorbable calcium. Soaking beans and grains before cooking can reduce phytate content.

- Excess Vitamin A – Vitamin A in the form of retinol (preformed A, from liver or supplements) is tricky. Moderate vitamin A is needed for bone growth, but high intake is harmful. Studies show that women consuming very high amounts of retinol (e.g. many vitamin A supplements or a lot of liver) had lower bone density and higher fracture risk. Excess vitamin A seems to block vitamin D’s effects, increasing bone resorption. To avoid this, do not take high-dose vitamin A supplements and be mindful of very rich sources (e.g. more than one serving of liver per week).

- Low-Carb or Crash Diets – Severely restricting calories or carbohydrates for weight loss can backfire on bones. Diets that cause rapid weight loss often lead to decreases in bone density and strength. For example, dieters who skip meals or follow extreme fasting may lower levels of bone-building hormones. While losing excess weight benefits joints, it’s important to do it gradually and consume enough protein, calcium and vitamin D during weight loss. Pair any diet with exercise to signal your bones to stay strong.

- Alcohol and Smoking – These lifestyle factors greatly affect bones. Chronic heavy alcohol use interferes with vitamin D metabolism and bone formation. Tobacco smoke contains toxins that weaken bone and reduce blood supply. One source notes that quitting smoking is recommended, and limiting alcohol (no more than 1–2 drinks a day) may enhance bone health.

In short, a whole foods diet – rich in vegetables, fruits, lean protein and healthy fats – supports strong bones better than a diet high in processed fare, sugar and salt.

Special Diets and Life Stages

Bone needs change with age and diet choices:

- Childhood and Adolescence: This is the time to build bone mass. Bones grow quickly during growth spurts, so adequate calcium, protein and vitamins D/K are vital. Encouraging children to drink milk or fortified juices, eat yogurt and include fruits, veggies and fish sets a foundation. Vitamin D status is especially important for kids – deficiency is common (up to 70% of U.S. children have low D levels). Parents and schools should promote outdoor play for vitamin D and bone loading through activity.

- Adult Maintenance: In early adulthood, focus shifts to maintaining the bone bank. Adults should aim for at least 1000–1200 mg of calcium daily (depending on age and sex). Meeting this goal is easier if your diet includes dairy or fortified alternatives at each meal. Continue weight-bearing exercise (walking, jogging, dancing, weights) to stimulate bone.

- Perimenopause and Menopause: Women experience a hormonal drop in estrogen that accelerates bone loss in their 40s and 50s. During and after menopause, attention to diet is crucial. Many experts recommend calcium plus vitamin D supplements at this stage to slow bone loss. Also include foods rich in vitamin K and soy isoflavones (like tofu, edamame, natto) which may offset estrogen decline. Regular weight training is very helpful at this age.

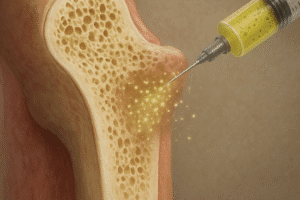

- Older Adults: After age 65, calcium absorption becomes less efficient and bones are more brittle. Seniors should get around 1200 mg of calcium daily, and continue vitamin D. Along with diet, it’s wise to have a bone density test to gauge status. Multivitamins containing vitamin D, calcium and vitamin B12 can be useful, but talk to a doctor or dietitian to avoid excessive intake of minerals like zinc or copper.

- Vegetarian/Vegan Diets: Completely plant-based diets can provide excellent nutrients but require some planning. Vegans need reliable sources of calcium (fortified plant milks, tofu, leafy greens), vitamin D (sun exposure, supplements) and vitamin B12 (fortified foods or supplements). One review warns that chronic vegetarian diets without attention to these nutrients can lead to bone loss and osteoporosis. However, a well-planned plant diet with adequate calories, protein and greens can maintain good bone health. For instance, combining beans with greens and sesame (tahini) or eating fortified plant milk can supply calcium.

- Athletes and Active Lifestyles: Athletes, particularly female athletes, have extra bone demands. Endurance athletes, dancers or gymnasts with very low body weight or missed periods may experience bone loss. These athletes need slightly higher calcium and vitamin D to support their intense training. Collagen supplements (with vitamin C) are sometimes used by athletes recovering from bone stress injuries, since collagen is critical for bone repair. In general, eating enough food to fuel training – including protein and dairy – is important.

Everyday Tips for Strong Bones

Here are practical strategies to weave bone-friendly nutrition into daily life:

- Eat a Rainbow of Foods. Aim for vegetables of all colors and plenty of fruits. Dark leafy greens, orange and yellow produce, red peppers and berries provide a spectrum of vitamins and minerals that support bone and overall health.

- Include Calcium Every Day. Spread your calcium sources throughout the day. For example, have yogurt with breakfast, cheese with lunch or dinner, and snacks like almonds or kale salad. If you drink cow’s milk or fortified plant milk, that’s an easy daily calcium boost.

- Don’t Forget Vitamin D. If you live in a place with limited sun, consider a vitamin D supplement (especially in winter). Aim for at least 600–800 IU per day (more if you are deficient) to help absorb that calcium.

- Balance Protein. Ensure each meal has a source of protein: eggs or tofu for breakfast, beans or meat at lunch, fish or legumes at dinner. This helps maintain bone matrix. But also eat plenty of fruits/veggies so the diet isn’t overly acid-forming.

- Limit Salt and Sugar. Use herbs and spices instead of extra salt. Cut back on sodas, sports drinks and sweet desserts, as these can leach calcium. If you crave something fizzy, try sparkling water with citrus slices.

- Stay Active. While not a nutrient, movement is as important as diet. Weight-bearing and resistance exercises (walking, dancing, lifting weights) stimulate bone remodeling. Try to move most days of the week and include some muscle-strengthening routines.

- Monitor Intake of Special Substances. Keep an eye on foods that affect mineral balance: limit alcohol, avoid very high doses of vitamin A, and moderate coffee and tea (they are fine in moderation but very high caffeine might impair calcium retention slightly).

- Consider Fortified Foods or Supplements Wisely. If your diet lacks certain nutrients, fortified choices can help. For example, calcium-fortified orange juice, cereals and dairy alternatives can fill gaps. Use supplements (like calcium or vitamin D pills) if needed, but follow recommended amounts. Getting too much of some bone nutrients (like vitamin A or some minerals) can be counterproductive.

- Check Your Diet Periodically. As we age or change diets (e.g., become vegetarian), re-evaluate your nutrition. A brief dietary review or blood test can catch hidden shortfalls early so you can adjust with food or supplements.

By focusing on nutrient-dense foods for bone health – such as dairy or fortified alternatives, leafy greens, lean protein, nuts and fish – and limiting detrimental habits, you can build and maintain a strong skeletal foundation. These eating patterns help bones maintain their density and strength well into later life. In turn, this means fewer fractures, better mobility and a higher quality of life. Proper nutrition is the unseen but powerful ally in the fight against osteoporosis and bone weakness.