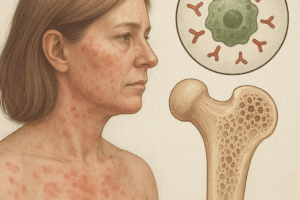

The Need for Advanced Bone Repair Methods

Bone injuries and disorders are a major challenge in medicine. Small fractures often heal on their own, but large defects from trauma, tumors or degenerative diseases overwhelm the body’s self-healing ability. Worldwide, more than 2 million bone graft surgeries (autografts or allografts) are performed each year to reconstruct critical bone defects. However, these traditional grafts have serious limitations: autografts (using the patient’s own bone) can cause donor-site pain and morbidity (up to 20%) and there is only limited bone available. Allografts (from donors) carry risks of immune rejection and infection. Even advanced therapies like bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) can induce bone formation but often degrade rapidly and require high doses. These challenges have led researchers to explore nanotechnology as a way to improve bone healing.

Nanotechnology and Bone Biology

Bone’s Natural Nanostructure

Bone itself is a natural nanomaterial. Roughly 60% of bone’s dry weight is mineral (hydroxyapatite) in nanometer-scale crystals, embedded in an organic collagen matrix. The collagen fibers in bone are about 50–500 nanometers thick, creating a nanoscale architecture that guides stem cells and osteoblasts to regenerate bone. In other words, bone cells thrive on a nanoscale scaffold. Modern nanomaterials can mimic these features: for example, synthetic scaffolds made of aligned nanofibers closely simulate bone’s collagen network, helping cells to align and form new bone tissue.

Why Nanotechnology?

At the nanometer scale, materials exhibit unique properties. Nanoparticles and nanostructured surfaces have vastly increased surface area and can be chemically modified with precision. This makes them excellent carriers for growth factors and drugs, and provides powerful biological cues. For instance, nanofibrous scaffolds or nanopatterned implants create a biomimetic topology: they imitate the extracellular matrix and effectively promote cell adhesion and signaling. Studies show that implants with nanometer-scale roughness encourage osteoblasts to deposit extracellular matrix much faster than conventional micro-rough implants.

Nanotechnology represents a paradigm shift in bone regeneration, enabling unprecedented control over biomaterials. Techniques like electrospinning (to make nanofibers) and 3D bioprinting (to build customized scaffolds) allow engineers to incorporate nanomaterials into bone grafts. These advances mean devices can combine structural support with biologically active nanoscale components, turning implants into active participants in healing.

Key Advantages of Nanotechnology in Bone Repair

- Biomimicry: Nanostructured materials imitate the natural bone matrix. Nanofibers and nanopatterns create an environment very similar to real bone, which helps stem cells and osteoblasts behave normally.

- High Surface Area: Nanoscale coatings and particles provide enormous surface area for cells and proteins to interact. This promotes faster cell attachment and proliferation.

- Targeted Delivery: Nanocarriers (like liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, or nano-hydroxyapatite) can deliver growth factors or drugs directly to the fracture site, with controlled, sustained release.

- Antibacterial Properties: Incorporating antibacterial nanoparticles (such as silver) into implants or cements provides a built-in infection defense.

- Enhanced Integration: Engineered nanomaterials can match bone’s mechanical properties and encourage stronger bonding (osseointegration) between implant and bone.

These benefits explain why nanostructured biomaterials have been proven superior at enhancing bone regeneration.

Nanomaterials Used in Bone Repair

Researchers use several classes of nanomaterials in bone engineering, each serving different roles:

Nanostructured Ceramic Biomaterials

Calcium phosphate ceramics (especially nano-hydroxyapatite, HA) are chemically similar to bone mineral. When processed at the nanometer scale, HA is highly osteoconductive: it supports new bone growth along its surface. Modern nano-HA scaffolds are engineered with controlled porosity and composition, greatly improving bioactivity and degradation profiles compared to older bulk ceramics. Researchers also introduce trace ions (Mg²⁺, Sr²⁺, Si⁴⁺, etc.) into nano-HA. For example, magnesium-substituted nano-HA enhances osteoblast activity and blood vessel formation, more closely mimicking natural bone mineral. Such nanoceramics can be used as particles, coatings, or 3D-printed blocks that gradually dissolve as new bone replaces them.

Nanofiber Polymer Scaffolds

Electrospinning can create mats of polymer nanofibers 50–500 nm in diameter. These fibrous meshes closely resemble the collagen network of bone. Cells adhering to nanofibers feel a familiar environment: they align along fibers and receive nanoscale mechanical cues that encourage osteogenic differentiation. Scientists describe this as a “triple cooperative” effect: the scaffold’s topology (fiber structure), attached biochemical signals (e.g. peptides, growth factors), and mechanical stiffness together drive stem cells to form bone. Nanofiber scaffolds are often loaded with drugs or growth factors directly in the fibers for controlled release. For instance, fibers can carry BMP-2 or antibiotics that release slowly as the polymer degrades. Nanofibers are a workhorse of bone tissue engineering because they can be tailored in composition, orientation and degradation rate.

Metallic Nanocoatings and Implants

Titanium and its alloys are standard for load-bearing implants, and nanotechnology enhances these metals. Creating nanostructured surfaces (e.g. titanium nanotubes or nano-rough oxide layers) dramatically improves osseointegration. Experiments show that osteoblasts produce extracellular matrix much faster on nanostructured Ti surfaces than on polished ones. Such surfaces can be made by anodization, acid-etching, or applying nanoscale coatings of HA or other ceramics.

Metals also gain new functions via nanocoatings. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exemplify this: coating orthopedic hardware with AgNPs imparts long-lasting antibacterial properties. AgNP-coated screws, bone cements and prostheses have shown significantly reduced infection rates in studies. The nanoparticles release Ag⁺ ions that kill bacteria, while careful engineering keeps the levels safe for human cells. This dual functionality—mechanical support plus infection control—is a key advantage of nanotechnology in implants.

Nanocomposites and Bioactive Glasses

Combining nanoceramics with polymers yields nanocomposites that are both strong and bioactive. For example, embedding nano-HA in a collagen or PLGA matrix creates a scaffold that mimics bone’s hybrid composition. These composites can be 3D-printed or molded into complex shapes. Nanocomposites benefit from each phase: the polymer provides toughness and degradability, while the ceramic phase presents bone-like chemistry to cells.

Bioactive glasses are another group. Sol–gel techniques produce nanostructured silicate or borate glasses with very high surface area. These nanoglasses release therapeutic ions (Si, Ca, P, etc.) that stimulate bone cells. When implanted, nanoglass surfaces rapidly form a biologically active HA layer, directly bonding to bone. Researchers are also exploring piezoelectric nanomaterials: since natural bone generates electrical signals under stress, piezoelectric nanofibers or nanoparticles might in future help cells sense mechanical load and respond by growing new bone.

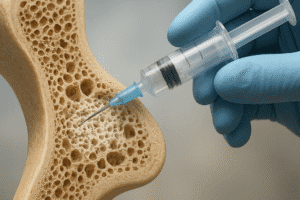

Nanoparticle Delivery Systems

Nanoparticles themselves act as tiny delivery vehicles for biomolecules, enabling a new class of therapies in bone repair:

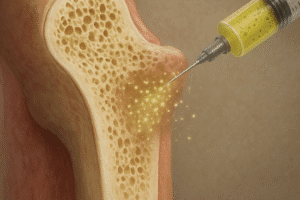

Controlled Release of Growth Factors

Growth factors (GFs) like BMP-2, VEGF and TGF-β are essential for bone healing, but they degrade quickly if injected freely. Nanoparticles solve this by encapsulating or adsorbing GFs onto their surface. For instance, biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles or HA nanoparticles can be loaded with BMP-2 and placed at the fracture. These carriers then release BMP-2 gradually, keeping a high local concentration with far smaller doses. This targeted delivery mimics the body’s natural healing signals and can greatly enhance osteogenesis. Similarly, nanoparticles can carry anti-inflammatory drugs or antibiotics directly to the healing bone, maximizing therapeutic effect and minimizing systemic side effects.

Stem Cell Carriers

Nanotechnology also supports cell-based therapies. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be delivered on nanostructured scaffolds or bound to nanoparticles. The scaffold provides a matrix that mimics the stem cell niche, improving cell survival and differentiation. Some strategies co-deliver MSCs with GF-loaded nanoparticles in the same scaffold. The nanoparticle scaffolds can also be designed to modulate the immune response: for example, certain nano-coatings may encourage a healing (M2) macrophage phenotype instead of an inflammatory one, thereby further promoting regeneration.

Smart Nanocarriers

Emerging “smart” nanoparticles release their cargo in response to local triggers. For example, a nanoparticle may release a drug only when it encounters the acidic environment of injured tissue, or in the presence of certain enzymes. Magnetic nanoparticles (e.g. iron oxide) can be externally heated to trigger on-demand drug release. By coupling drug delivery with stimuli-responsiveness, such systems aim to deliver therapeutic agents only at the right time and place, closely emulating the spatiotemporal control of natural bone healing.

Fabrication Techniques for Nano-Scaffolds

Creating nanostructured materials requires advanced manufacturing:

- Electrospinning: A polymer solution or melt is drawn by an electric field into nanofibers (tens to hundreds of nm). This produces mesh mats of aligned or random fibers, which can be collected into any shape or layered with cells/drugs.

- 3D Bioprinting: Computer-driven printing builds scaffolds layer by layer. “Bio-inks” that contain nanoparticles, polymers and even cells can be extruded. Modern bioprinters can deposit nanocomposite materials with precise porosity and architecture, tailoring implants to patient-specific shapes.

- Sol–Gel and Chemical Synthesis: Nanoceramics and bioactive glasses are often synthesized in solution (sol–gel) or hydrothermally, allowing control over particle size and porosity. These nanoparticles can then be formed into bulk scaffolds or coatings.

- Surface Modification: Existing implants are modified at the nano-scale by techniques like anodization (to create titania nanotubes), laser texturing, or nanoparticle coating (e.g., dipping an implant in a HA nanoparticle suspension and sintering it on). These methods impose nanoscale features on otherwise conventional hardware.

By integrating macro-scale (overall shape) and micro/nano-scale (internal architecture) processes, engineers build hierarchical scaffolds that mimic real bone from the organ down to the molecular level.

Clinical Applications and Examples

Research on nanotechnology for bone repair is rapidly advancing, with several applications in use or development:

- Antibacterial Implants: Silver nanoparticle coatings on surgical screws, pins and joint prostheses have entered clinical use. These AgNP-modified devices show significantly fewer post-operative infections in orthopedic patients.

- Synthetic Bone Grafts: Many commercial bone graft substitutes now contain nano-HA or nano-βTCP. Newer products feature nanoscale porosity or composite layers designed to encourage faster vascular ingrowth and remodeling.

- Dental Bone Regeneration: Nanotechnology has improved oral surgery outcomes. Nano-structured membranes and bone grafts help rebuild jawbone after tooth loss, and nano-rough dental implants integrate faster and more reliably.

- Injectable Scaffolds: Some therapies use injectable hydrogels laden with nanoparticles and cells. For example, Thorpe et al. developed an injectable nanocomposite hydrogel containing nano-hydroxyapatite. In vitro studies showed this gel supported human MSCs and induced their differentiation into bone-forming cells.

- Combined Treatments: In animal models, fractures treated with nanofiber scaffolds plus growth factors heal more quickly than with either alone. Experimental treatments are also exploring pairing stem cells with nanoparticles to create self-contained healing implants.

These examples illustrate a shift from passive bone grafts to bioactive, multifunctional systems that actively orchestrate healing at the site of injury.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the promise, challenges remain:

- Biocompatibility: All nanomaterials must be thoroughly tested. Some nanoparticles can provoke unintended immune responses or toxicity. For instance, high concentrations of silver ions can inhibit bone cells, so dosage must be carefully controlled.

- Regulatory Hurdles: Complex nanotech implants (especially those combining scaffold and drug) face extensive regulatory scrutiny. Long-term safety and durability must be demonstrated before they reach patients.

- Manufacturing: Producing nanomaterials with consistent quality at large scale can be difficult and expensive. Maintaining uniform nanoparticle size and distribution is crucial for reliable behavior.

- Mechanical Strength: Pure nanoceramics can be brittle. Achieving the right balance of strength and resorption rate in a bioactive scaffold is an ongoing engineering problem.

- Controlled Delivery: Optimizing release kinetics of drugs and survival of delivered cells in vivo is complex. Ongoing research aims to fine-tune how and when nano-delivered factors are released in the dynamic healing environment.

Looking ahead, next-generation strategies include “smart” scaffolds and interdisciplinary approaches. Researchers are applying artificial intelligence to design optimal nanocomposite formulations. Some teams are developing nanosensors embedded in implants to monitor healing in real time. There is also growing focus on ensuring ethical and environmental safety of nanomaterials in medicine.

Overall, nanotechnology is transforming bone repair by providing tools to engineer healing from the bottom up. Instead of merely filling defects, future therapies will actively guide each step of regeneration at the molecular level. If the remaining challenges can be addressed, nanotech-enhanced treatments promise faster, more complete healing and fewer complications than ever before.