Osteoporosis is a chronic condition characterized by a gradual decline in bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, leading to increased susceptibility to fractures. As the global population ages, understanding how bone density changes over time and the strategies to maintain skeletal health have become critical areas of research in bone and medicine. This article explores the mechanisms underlying osteoporosis progression, the various factors that accelerate bone loss, diagnostic methods, and evidence-based approaches to prevention and management.

Understanding Osteoporosis and Bone Density

Bone Structure and Remodeling

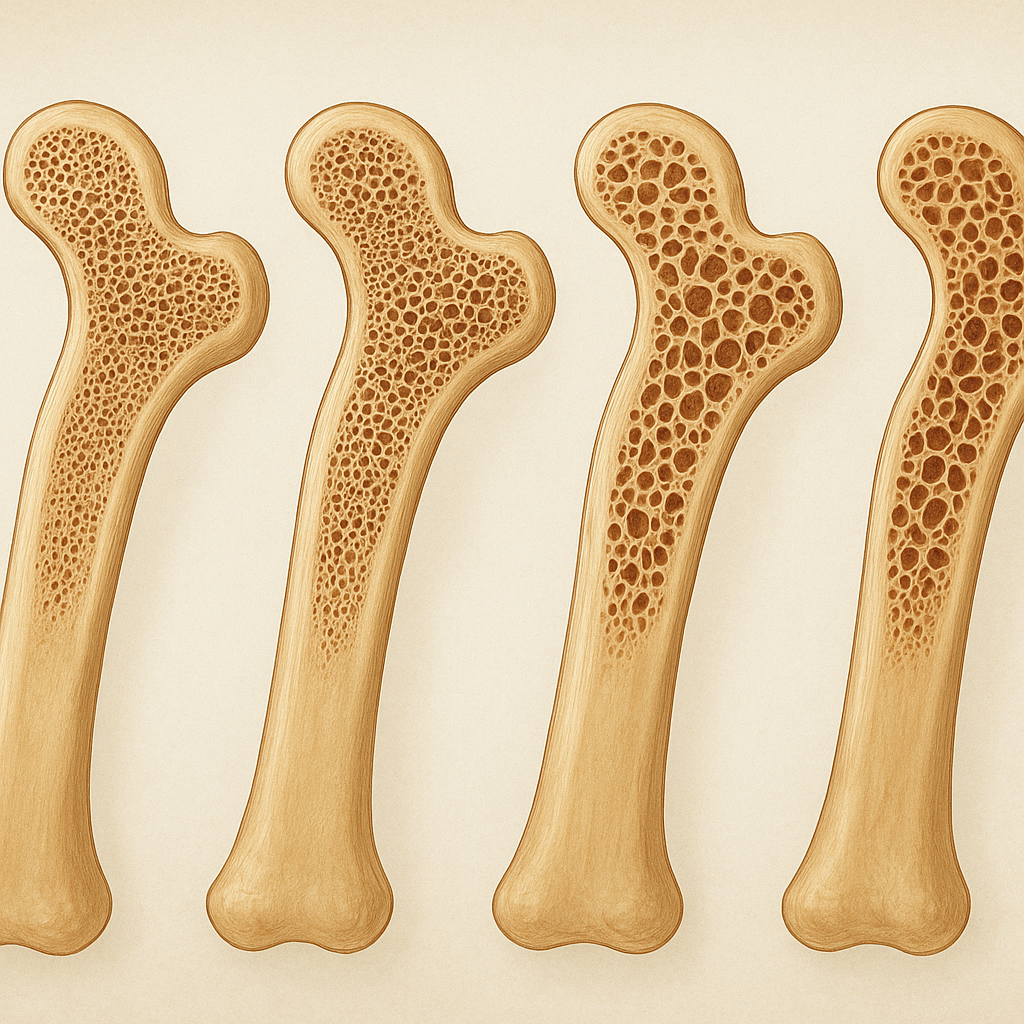

Healthy bones are dynamic organs undergoing continuous remodeling—a tightly regulated process in which old bone is resorbed by osteoclasts and new bone is formed by osteoblasts. This balance ensures maintenance of bone strength and integrity. In osteoporosis, the equilibrium shifts toward excessive resorption, causing reductions in bone mineral density and changes in trabecular architecture. Over time, these changes translate into microcracks, cortical thinning, and weakened structural support.

Role of Calcium and Vitamin D

Calcium and vitamin D are fundamental to bone health. Calcium serves as the primary mineral component that confers hardness, while vitamin D enhances intestinal calcium absorption and regulates osteoblast and osteoclast activity. Insufficient intake of these nutrients leads to secondary hyperparathyroidism, accelerating bone turnover and net loss of mineralized matrix. Chronic deficiency can set the stage for early-onset osteoporosis, even in younger individuals.

Factors Influencing Bone Loss Over Time

Aging and Hormonal Changes

With advancing age, bone formation activity declines, partly due to senescence of osteoprogenitor cells. In women, the precipitous drop in estrogen levels after menopause dramatically increases bone resorption, resulting in an annual decrease of up to 2–3% in bone mass during the first five to ten years post-menopause. Men experience a more gradual decline in testosterone and estrogen, but still face progressive bone thinning. Hormonal imbalances, including hyperthyroidism or glucocorticoid excess, further aggravate skeletal fragility.

Lifestyle and Nutritional Factors

Modifiable lifestyle factors play a pivotal role in bone health trajectory:

- Physical Inactivity: Lack of weight-bearing exercise reduces mechanical loading signals essential for osteoblast stimulation.

- Excessive Alcohol and Smoking: Both contribute to impaired calcium absorption, oxidative stress in bone cells, and altered hormone metabolism.

- Poor Nutrition: Diets low in protein, calcium, and vitamin D accelerate bone loss, as do diets high in salt or caffeine which increase urinary calcium excretion.

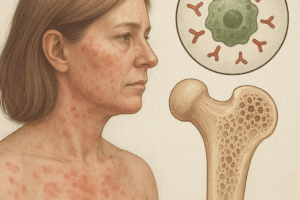

Genetic and Medical Conditions

Family history and genetic predisposition account for 60–80% of peak bone mass variance. Mutations in genes regulating collagen formation, vitamin D receptors, or cytokine production can predispose individuals to low bone density. Additionally, chronic inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., celiac disease), and certain medications (e.g., anticonvulsants, proton pump inhibitors) can impair bone remodeling and mineralization.

Diagnosis and Monitoring

Bone Density Tests and Imaging

The gold standard for diagnosing osteoporosis is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which quantifies bone mineral density at key sites such as the lumbar spine and hip. T-scores compare an individual’s BMD to a young adult reference; a T-score ≤ –2.5 confirms osteoporosis. Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) and peripheral DXA provide additional insights into trabecular versus cortical bone compartments. Vertebral fracture assessment and high-resolution peripheral QCT (HR-pQCT) can detect early microarchitectural deterioration.

Biochemical Markers and Risk Assessment

Biochemical markers of bone turnover, including serum C-terminal telopeptide (CTX) and procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP), offer dynamic information about resorption and formation rates. While variability limits their diagnostic standalone utility, trends in marker levels can guide therapy response. Clinical risk assessment tools, such as FRAX®, integrate BMD with clinical risk factors—age, previous fracture, family history, glucocorticoid use—to estimate 10-year fracture probability.

Strategies for Prevention and Management

Nutrition and Supplementation

A balanced diet rich in calcium (1,000–1,200 mg/day) and vitamin D (800–1,000 IU/day) is foundational. Dairy products, fortified beverages, leafy greens, and fish with edible bones are ideal sources of calcium. Fatty fish, egg yolks, and sunlight exposure facilitate vitamin D synthesis. In individuals unable to meet requirements through diet alone, supplementation is advised. Additional nutrients—magnesium, vitamin K2, and trace minerals like zinc—support collagen cross-linking and mineral deposition.

Exercise and Physical Activity

Mechanical strain from regular weight-bearing and resistance exercises stimulates osteoblast proliferation, improving bone mass and geometry. Recommended regimens include:

- High-impact activities (e.g., jumping, stair climbing) for younger or lower-risk individuals.

- Resistance training targeting major muscle groups at moderate intensity (60–80% of one-repetition maximum).

- Balance and posture exercises (e.g., tai chi, yoga) to reduce fall risk in older adults.

Consistency is key: at least three sessions per week over months to years are necessary to achieve and maintain skeletal benefits.

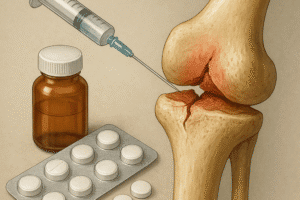

Pharmacological Treatments

For patients at high fracture risk, several drug classes modulate bone remodeling:

Anti-resorptive Agents

- Bisphosphonates (e.g., alendronate, risedronate) inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and reduce vertebral and non-vertebral fracture incidence.

- Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting RANKL, offers reversible suppression of osteoclast activity when administered biannually.

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) mimic estrogen’s bone-protective effects without stimulating breast or endometrial tissue.

Anabolic Therapies

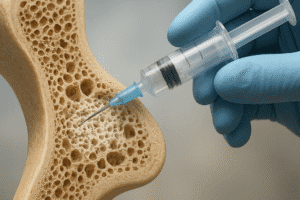

- Teriparatide, a recombinant parathyroid hormone fragment, transiently increases bone formation when given daily by injection.

- Romosozumab, an anti-sclerostin antibody, both stimulates bone formation and modestly inhibits resorption.

Choice of agent depends on patient characteristics, risk profile, tolerance, and cost considerations. Regular reassessment ensures optimal duration and sequence of therapies.

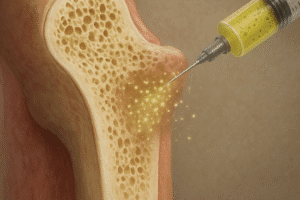

Emerging Interventions

Novel approaches under investigation include stem cell therapy to repopulate osteoblast precursors, gene editing to correct hereditary defects, and targeted delivery of growth factors like BMPs (bone morphogenetic proteins). Advances in biomaterials and tissue engineering may one day allow in vivo regeneration of bone for severe osteoporotic lesions.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis represents a progressive threat to musculoskeletal health, yet a comprehensive understanding of bone remodeling mechanisms, risk factors, diagnostic tools, and multifaceted prevention and treatment strategies can mitigate its impact. Lifelong attention to nutrition, physical activity, and appropriate medical interventions empowers individuals to preserve bone strength, reduce fracture risk, and maintain quality of life as they age.