The decline in ovarian function during menopause triggers a cascade of changes that profoundly influence skeletal integrity. As estrogen levels wane, women become increasingly susceptible to accelerated bone turnover, diminished bone mass, and an elevated risk of fractures. Understanding the interplay between hormonal shifts and bone physiology is essential for developing effective strategies to preserve skeletal strength and prevent debilitating complications.

Physiological Changes During Menopause

Menopause marks the end of reproductive capacity and is characterized by a significant reduction in circulating estrogen. This hormonal withdrawal alters the balance between bone formation and resorption. Under normal conditions, osteoblasts and osteoclasts maintain skeletal homeostasis through tightly regulated remodeling. With estrogen deficiency, however, the coupling of these processes becomes disrupted, favoring resorption over formation. The result is a net loss of bone mineral density that accelerates in the early postmenopausal years.

Mechanisms of Bone Loss

Estrogen Deficiency and Remodeling

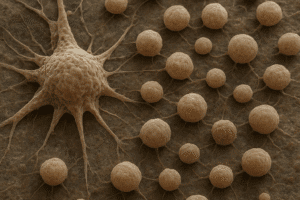

Estrogen exerts antiresorptive effects by inhibiting osteoclast differentiation and activity. It downregulates the expression of critical cytokines such as RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB Ligand) and upregulates osteoprotegerin, a decoy receptor that binds RANKL. When estrogen levels fall, osteoclastogenesis intensifies, leading to increased bone matrix breakdown. Concurrently, osteoblast lifespan and anabolic activity diminish, preventing adequate replacement of resorbed bone.

Cellular and Molecular Pathways

At the molecular level, estrogen deficiency amplifies proinflammatory mediators like interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. These cytokines promote osteoclast survival and bone resorption. Additionally, oxidative stress within the bone microenvironment rises, further impairing osteoblast function. Genetic factors influence individual susceptibility: polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor gene and in cytokine promoters can modulate the severity of bone loss during menopause.

Clinical Implications and Risk Assessment

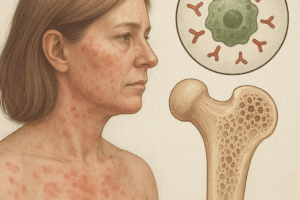

Postmenopausal women face a heightened incidence of osteoporosis, a systemic skeletal disorder defined by low bone density and microarchitectural deterioration. Fragile bones predispose to fractures, especially in the hip, spine, and wrist. Vertebral compression fractures can lead to chronic pain, reduced mobility, and loss of height, while hip fractures carry substantial morbidity and mortality rates in the elderly.

Risk assessment tools integrate clinical factors and bone density measurements to estimate fracture probability. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) remains the gold standard for quantifying bone mineral density. The World Health Organization’s FRAX algorithm combines DXA results with variables such as age, sex, body mass index, prior fracture history, glucocorticoid use, smoking, and alcohol intake to predict 10-year fracture risk.

- Age over 50 years

- Family history of osteoporosis

- Low body mass index

- Early menopause (before age 45)

- Chronic glucocorticoid therapy

- Rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory conditions

- Smoking and excessive alcohol consumption

Prevention Strategies and Therapeutic Approaches

Maintaining skeletal health in postmenopausal women relies on a multipronged approach that includes lifestyle modification, nutritional support, pharmacotherapy, and regular screening.

- Calcium intake of 1000–1200 mg per day, preferably from dietary sources such as dairy products, leafy greens, and fortified foods.

- Vitamin D supplementation (800–2000 IU daily) to optimize calcium absorption and regulate bone remodeling.

- Weight-bearing exercise and resistance training to stimulate osteoblast activity and enhance muscle strength, thereby reducing fall risk.

- Smoking cessation and moderation of alcohol intake to eliminate lifestyle risk factors.

- Fall prevention strategies, including home safety assessments and balance training, to minimize injury risk.

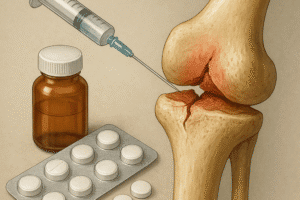

Pharmacological interventions target bone resorption and formation. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) restores estrogen levels, diminishing bone turnover and preserving density. However, HRT carries potential risks—such as thromboembolic events and certain cancers—that must be weighed against benefits, especially in long-term use. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like raloxifene provide estrogenic effects on bone with antagonist activity in breast tissue.

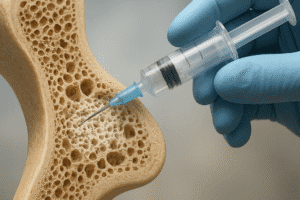

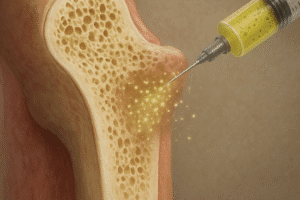

Bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid) bind to hydroxyapatite in bone and induce osteoclast apoptosis, effectively reducing fracture risk. Denosumab, a monoclonal antibody against RANKL, offers an alternative mechanism by directly inhibiting osteoclast formation. Parathyroid hormone analogs (teriparatide) and newer agents like romosozumab (a sclerostin inhibitor) stimulate bone formation, representing advanced options for severe osteoporosis unresponsive to first-line therapies.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

Innovations in molecular biology and imaging are refining our understanding of postmenopausal bone health. High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) enables detailed assessment of trabecular and cortical microarchitecture. Biomarkers such as bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, C-terminal telopeptide, and sclerostin levels provide real-time insights into remodeling dynamics and treatment response.

Gene therapy and regenerative medicine hold promise for enhancing osteoblast function and reversing bone loss. Investigations into gut microbiome modulation suggest that probiotics may influence calcium metabolism and systemic inflammation, offering a novel adjunct to conventional care. Personalized medicine approaches, leveraging genetic and biochemical profiling, aim to tailor interventions based on individual risk profiles and therapeutic responsiveness.