Bone pain affects individuals across all age groups and can stem from a wide range of underlying conditions. Understanding the complex interplay of structural, metabolic, and systemic factors is essential to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and to guide effective therapy. This article explores the multifaceted causes of bone discomfort, examines the hurdles clinicians face during evaluation, and highlights contemporary approaches to patient care.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Bone tissue is remarkably dynamic, continuously undergoing remodeling through the coordinated actions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Disruptions in this equilibrium can manifest as pain. The principal categories of bone pain etiology include:

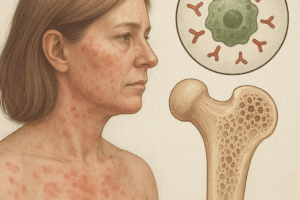

- Inflammatory processes: conditions such as osteomyelitis or rheumatoid arthritis that trigger cytokine-mediated nociception.

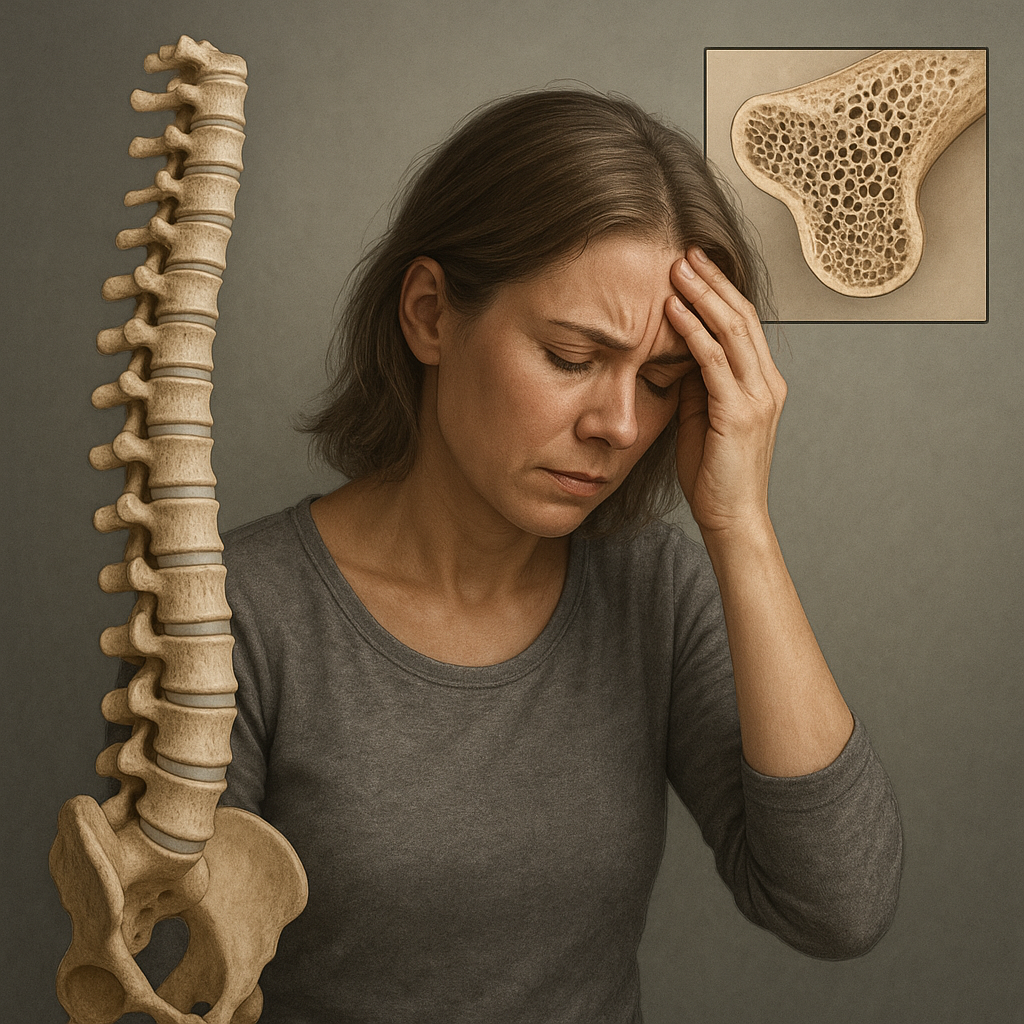

- Metabolic disorders: osteoporosis, osteomalacia, and hyperparathyroidism alter mineral homeostasis and weaken the skeletal matrix.

- Trauma and mechanical injury: fractures, stress fractures, and microtrauma from repetitive activity.

- Neoplastic involvement: primary bone tumors (e.g., osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma) or secondary metastases from breast, prostate, or lung carcinoma.

- Hereditary skeletal dysplasias: such as osteogenesis imperfecta, leading to bone fragility from defective collagen.

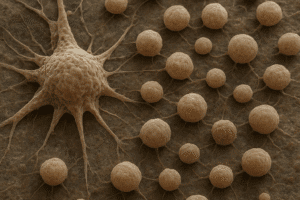

Mechanisms of Pain Generation

The sensation of bone pain arises from irritation of periosteal nerves or inflammation-induced chemical mediators. In malignancies, tumor cells may secrete proteolytic enzymes causing microfractures, while in osteomyelitis, bacterial toxins and host immune responses intensify nociceptive signaling. Additionally, changes in bone vascularity and intraosseous pressure contribute to persistent discomfort.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms

Bone pain exhibits considerable variability in onset, intensity, and associated features. A careful history and physical examination are pivotal in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

History Taking

- Onset and duration: acute versus chronic timeline helps distinguish traumatic from degenerative or neoplastic causes.

- Pain characteristics: sharp, dull, throbbing, or night pain—particularly nocturnal pain relieved by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may suggest malignancy.

- Aggravating and alleviating factors: weight-bearing activities, rest, or response to analgesics.

- Systemic symptoms: fever and chills (suggesting infection), weight loss, and night sweats (raising suspicion for malignancy or chronic inflammatory disorders).

- Past medical history: prior fractures, endocrine diseases, or family history of bone disorders.

Physical Examination

Inspection and palpation focus on identifying tenderness over bone shafts or joints, localized swelling, erythema, and range-of-motion limitations. Neurological assessment ensures exclusion of associated nerve compression or referred pain from adjacent structures.

Diagnostic Modalities and Challenges

Accurate evaluation of bone pain demands a combination of laboratory assays, imaging techniques, and sometimes invasive procedures. Each modality has inherent strengths and limitations, contributing to diagnostic complexity.

Laboratory Investigations

- Complete blood count and inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) for infection or systemic inflammation.

- Serum calcium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, and vitamin D levels to assess metabolic bone diseases.

- Tumor markers (e.g., PSA, CA 15-3) when metastatic disease is suspected.

Imaging Techniques

- Plain radiography: first-line for detecting fractures, lytic or sclerotic lesions, but limited sensitivity in early disease.

- Computed tomography (CT): superior for cortical bone assessment and surgical planning.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): excellent soft-tissue contrast, ideal for marrow infiltration and early osteomyelitis.

- Nuclear medicine bone scan: whole-skeleton evaluation of metabolic activity, useful in multifocal disease.

- Positron emission tomography (PET): high sensitivity for neoplastic processes, often combined with CT (PET-CT).

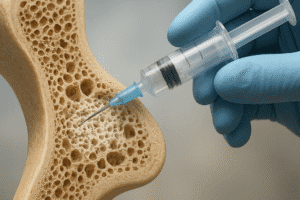

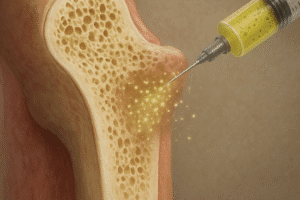

Biopsy and Histopathology

When imaging and labs are inconclusive, a percutaneous or open biopsy may be indispensable. Histological analysis confirms malignancy, infection, or specific bone dysplasia. However, sampling error and procedural risks pose diagnostic challenges.

Treatment Strategies and Management

Effective management of bone pain is tailored to the underlying cause, with goals of pain relief, restoration of function, and prevention of complications.

Nonpharmacological Approaches

- Physical therapy: weight-bearing exercises to enhance bone density, muscle strengthening to support skeletal integrity.

- Orthotic devices: bracing to reduce skeletal stress in stress fractures or deformities.

- Nutrition and lifestyle modification: adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, smoking cessation, and moderation of alcohol.

Pharmacological Therapies

- Analgesics: acetaminophen, NSAIDs for mild to moderate pain; opioids for severe nociceptive pain.

- Bisphosphonates and denosumab: antiresorptive agents for osteoporosis and bone metastases.

- Antibiotics: targeted antimicrobial therapy in osteomyelitis, often requiring prolonged courses and surgical debridement.

- Chemotherapy and radiotherapy: for primary bone malignancies or metastatic lesions, combined with surgical resection when feasible.

Interventional and Surgical Options

In refractory cases, vertebroplasty, radiofrequency ablation, or surgical stabilization of pathological fractures may be warranted. Multidisciplinary coordination ensures optimal outcomes and minimizes procedural risks.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Advances in molecular biology and imaging are illuminating novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. For instance, research into bone microenvironment signaling pathways may yield biologics that modulate osteoclast activity with greater specificity. Furthermore, artificial intelligence–driven image analysis holds promise to enhance early detection of subtle lesions. Personalized medicine approaches, integrating genetic profiling and pharmacogenomics, aim to refine management strategies and improve patient-centered outcomes. As our understanding of skeletal pathobiology deepens, clinicians will be better equipped to overcome the diagnostic challenges of bone pain and transform patient care.