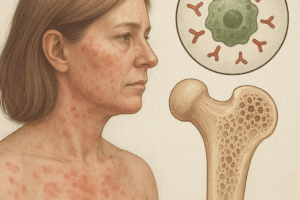

Bone imaging technology encompasses a range of medical imaging methods designed to visualize and analyze the structure and health of the skeletal system. From classic X-rays that reveal fractures to advanced 3D modalities like computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), these tools help healthcare professionals diagnose and monitor a wide variety of bone-related conditions. With continued innovation, modern bone imaging provides greater detail and insight than ever before.

Understanding bone imaging is essential for patients and providers alike. These technologies support orthopedic and general healthcare by highlighting fractures, bone density changes, tumors, infections, joint conditions, and more. Each imaging modality has unique strengths and limitations, and choosing the right technique depends on the clinical scenario. In this comprehensive guide, we explore the principles, benefits, and uses of major bone imaging modalities. We also touch on emerging technologies and future trends in the field.

How Bone Imaging Works: Principles and Purpose

Bone tissue is hard and dense, which makes it stand out in various imaging modalities. X-rays and CT scans work by sending X-ray beams through the body; bones absorb much of the radiation and appear bright on the resulting images. MRI uses strong magnets and radio waves to visualize bone marrow and soft tissues around bone, highlighting differences in magnetic properties rather than density. Ultrasound employs sound waves that bounce off tissue interfaces; it is typically used for soft tissues and can visualize areas near bone, but sound waves cannot penetrate deep through thick bone. Despite these differences, each imaging technique ultimately produces images (two-dimensional or three-dimensional) that reveal the shape, structure, and composition of the skeleton.

Bone imaging relies on differences in how each modality interacts with bone tissue. X-rays produce an image where bones appear white due to high absorption of radiation, while soft tissues appear shades of gray or black. The resolution of imaging indicates how small a detail can be seen; standard X-ray film has very high spatial resolution for bone edges, but it compresses a 3D structure into a 2D image. CT scans add the ability to separate layers. Each CT slice has a thickness (often under 1 mm in clinical scanners), allowing tiny bone fragments to be seen that would blur together on an X-ray. CT also uses a gray-scale map of Hounsfield units to distinguish very dense bone from less dense tissue. MRI image contrast is based on tissue composition. Bone marrow (rich in fat) has a different signal than inflamed or cancerous marrow. For example, normal fatty marrow is bright on T1-weighted images, whereas fluid or tumor makes a bone appear bright on T2-weighted or STIR images. Overall, bone imaging is the interplay of physics and biology: the goal is to highlight the properties of bone (mineral content, density, inflammation) that change in disease. Understanding the imaging physics helps medical teams interpret why bones look the way they do on each scan type.

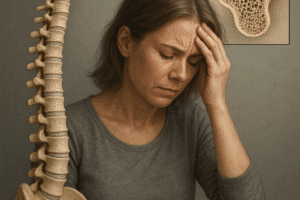

The goals of bone imaging include detecting fractures, assessing bone density, and identifying abnormalities. For example, spotting a small crack or stress fracture can prevent a larger injury in the future. Doctors use imaging to monitor conditions like osteoporosis (thinning bones) by measuring bone density over time. Imaging also helps find bone tumors or infections and tracks healing after a fracture or surgery. In some cases, real-time imaging like fluoroscopy (a live X-ray “movie”) guides tools and verifies correct placement during treatments, ensuring procedures are safe and accurate. The following list highlights common uses of bone imaging:

- Diagnose fractures and bone injuries

- Measure bone density for osteoporosis screening

- Detect bone tumors and infections

- Monitor healing after injury or surgery

- Guide injections and surgical procedures

Traditional Radiography and X-ray Techniques

X-ray radiography was the first widely used bone imaging method, revolutionizing medicine since its discovery in the 1890s. A standard X-ray image quickly captures the outline of bones and joints using ionizing radiation. It is the most common way to find broken bones, joint dislocations, and obvious structural changes. X-ray pictures are fast and relatively inexpensive. They show dense bone tissue clearly, while muscles and organs appear lighter or nearly transparent.

However, conventional X-ray images are two-dimensional and can miss some problems. Overlapping bones or subtle cracks might not be visible. Also, X-rays involve a small dose of radiation. Modern radiography has improved dramatically: digital X-ray detectors produce clearer images instantly on a computer. New techniques like digital tomosynthesis (taking multiple angled X-rays) can create a layered view of the bone, improving detection of certain fractures. Low-dose X-ray technology also helps reduce radiation exposure. Despite these advances, X-ray remains the first-line tool for initial fracture assessment and guiding orthopedic treatment, thanks to its speed and simplicity.

Modern X-ray equipment has largely replaced film with digital flat-panel detectors. Digital systems allow instant viewing on monitors, easy image storage, and post-processing adjustments (like zoom or contrast enhancement) to clarify details. X-ray machines vary from large stationary units in radiology departments to portable devices. Portable X-ray units can be brought to the bedside in emergency rooms or intensive care, allowing imaging of patients who cannot be moved. Standard positions for X-rays (such as anterior-posterior and lateral views) are used so radiologists can interpret the bone orientation accurately. For complex injuries, multiple views at different angles may be taken to catch hidden fractures.

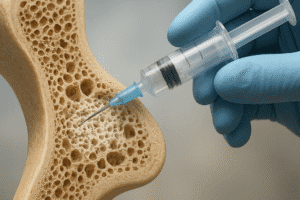

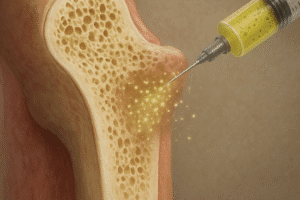

Fluoroscopy

Fluoroscopy is a special type of X-ray imaging that provides real-time moving images. It works like an X-ray “movie,” showing continuous images of bones and joints. Fluoroscopy is used during surgeries and interventions to guide needles, wires, and implants. For example, during joint injections or fracture repairs, fluoroscopy lets doctors see the bone in motion and confirm that instruments are placed correctly. Procedures often guided by fluoroscopy include arthrography (injecting dye into a joint for MRI or X-ray of the joint), vertebroplasty (cement injection into a fractured spine), and checking hardware placement after a fracture repair. Fluoroscopy remains a valuable real-time imaging technology in the operating room and intervention suite.

Computed Tomography (CT)

Computed tomography (CT) is an advanced X-ray technique that produces detailed cross-sectional images of the body. During a CT scan, an X-ray source and detectors rotate around the patient, taking many slices that a computer combines into a 3D image. CT scans excel at showing complex bone structures in high resolution. They are often used when a fracture is suspected but not clearly seen on a plain X-ray, or when surgeons need a precise 3D map of the bone (for example, before spine surgery or reconstruction). CT provides much more detail than a regular X-ray. It is the preferred method for complex fractures, pelvic injuries, and joint planning.

CT provides much more detail than a regular X-ray, but it involves a higher dose of radiation. Doctors use CT judiciously, applying dose-reduction techniques and shielding to protect patients. Many scanners now automatically adjust the X-ray dose based on patient size to minimize exposure. A CT scan is fast (just a few seconds of scanning) and can image large parts of the body quickly in emergencies, which makes it valuable in trauma centers. Modern CT scanners can also take images very quickly and are often used in trauma “pan-scans” to image the whole body rapidly. The 3D nature of CT allows doctors to view images in multiple planes; for example, images can be viewed in sagittal (side) or coronal (front) slices to better understand complex fractures.

CT scans can be enhanced with contrast dyes injected into a vein. This allows the scan to highlight blood vessels and differentiate normal bone marrow from infiltrating cancer or infection. For example, a CT with contrast can show whether a bone lesion has a blood supply (suggesting an active tumor) versus being a healed scar. CT technology has also advanced with dual-energy techniques that use two X-ray energy levels. This can help distinguish certain materials (like uric acid crystals versus bone) and can provide virtual non-contrast images, sometimes sparing the patient an extra scan. Photon-counting CT is another new development that promises higher resolution images of bone at lower radiation doses, although it is still in early clinical use.

Cone-Beam CT

Cone-beam CT (CBCT) is a variation of CT imaging that uses a cone-shaped X-ray beam and a specialized detector. It is commonly used in dentistry, ear/nose/throat, and extremity imaging. Cone-beam CT machines rotate around a smaller area (like the jaw or a limb) and generate 3D images with high bone detail but with lower radiation dose than a conventional CT. It is often used to evaluate jaw lesions, impacted teeth, and small bone structures like the wrist or foot. Dental offices use CBCT for implant planning or orthodontic assessment of jaw bones. Orthopedic practices may use small CBCT units to get detailed images of hand or foot bones. CBCT provides high spatial resolution of bone but has limited soft tissue contrast compared to full CT.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses a powerful magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed images of the body. Unlike X-rays or CT, MRI does not directly image cortical bone. Instead, MRI visualizes bone marrow and all the soft tissues around the bone (muscles, tendons, ligaments, cartilage). Bone itself appears dark on most MRI sequences, but the marrow inside produces signal. MRI is extremely useful for detecting bone marrow changes, tumors, inflammation, or subtle injuries like bone bruises and stress fractures that do not show up on other scans.

MRI is especially valuable for diagnosing certain bone conditions that other modalities can miss. For example, an MRI can detect bone marrow edema – fluid accumulation inside bone marrow that occurs after a bone bruise or microfracture. This is not visible on X-ray or CT, but shows up bright on fluid-sensitive MRI sequences (STIR or T2-weighted). Detecting marrow edema can help explain bone pain when other imaging is negative. MRI is also the method of choice for soft tissue tumors affecting bone, such as osteosarcoma. The tumor extent into bone marrow and surrounding muscle or joint space is clearly depicted on MRI, which is essential for planning surgical removal. In spine imaging, MRI can show compression fractures, ligament injuries, and any spinal cord or nerve impingement. It is widely used to evaluate intervertebral discs, facet joints, and spinal canal anatomy next to the bone.

Because MRI shows the body in slices from any direction, it is very helpful in complex anatomy. Doctors often take images in multiple planes (axial, sagittal, coronal) in one study. New developments like metal artifact reduction techniques help get clearer images in patients with implants. Some MRI scanners can do 3D volumetric imaging, which can be reformatted into arbitrary planes after the scan. MRI scanners can acquire different types of images (called sequences) by adjusting parameters. For example, T1-weighted images show fat clearly, while T2-weighted or STIR images highlight fluid and inflammation. Contrast agents (gadolinium) may be injected for better visualization of blood vessels or to characterize tumors.

One major advantage of MRI is that it uses no ionizing radiation. This makes MRI safe for children and for follow-up imaging. MRI can be lengthier (often 20–45 minutes) and more expensive than X-ray or CT. The scanner is a large tube, and patients must lie still inside. Some people feel claustrophobic; open MRI machines are an option but may give lower image quality. Certain patients cannot have MRI at all, such as those with certain pacemakers, implanted metal clips in the brain, or shrapnel in the eye. Most orthopedic implants like screws and plates made of titanium or stainless steel are safe in MRI, but specialized MRI scans may be needed to reduce metal distortion.

Ultrasound in Bone Imaging

Ultrasound is not the first tool for looking at bone, because high-frequency sound waves do not travel through dense bone. However, ultrasound has specialized roles related to bones and joints. One use is assessing bone health without radiation. For example, quantitative ultrasound (QUS) of the heel bone (calcaneus) can estimate bone density as a quick osteoporosis screening. A newer ultrasound technique called Radiofrequency Echographic Multi-Spectrometry (REMS) scans the spine and hip to measure bone density and quality without exposing the patient to X-rays. These methods provide a safe, radiation-free way to monitor bone strength in patients at risk of osteoporosis.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound is popular in sports and rheumatology medicine. It can evaluate tendons that attach to bone (such as the Achilles tendon or rotator cuff) for tears or inflammation. Because it is dynamic, doctors can have patients move a joint or tendon during the scan and see it in action. Ultrasound can also measure swelling or fluid around bones and joints, such as in arthritis. In emergency settings, point-of-care ultrasound can quickly check for certain fractures in children or small bones. For example, an ultrasound exam can sometimes identify a wrist fracture or a hip effusion (fluid in the hip joint) in a child much faster and without radiation. However, X-rays are usually needed to confirm the exact fracture line if a break is suspected.

In pediatric orthopedics, ultrasound is famously used to check newborn hips for developmental dysplasia, since the hip bones have not fully ossified. By six months of age, much of the hip joint is still cartilage (invisible on X-ray) but can be seen on ultrasound. This lets doctors screen infants early without X-rays. Ultrasound also guides interventions around bone: for example, a clinician may use ultrasound to guide a steroid injection into a joint or to aspirate fluid. Ultrasound has no harmful radiation and can be done at the bedside. A skilled technician or doctor can move the probe in real-time to examine joints. The image is in grayscale, but Doppler mode can show blood flow, which helps detect inflammation or infection near bone. Despite its limitations with deep bone, ultrasound is a versatile adjunct in bone and joint imaging.

Bone Densitometry and Bone Quality Assessment

Alongside visualizing bone structure, several imaging methods measure bone density and strength. The most established test is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA or DEXA). A DXA scan is a special low-dose X-ray of the hip and spine (sometimes the forearm) that quantifies bone mineral content. The result is compared to a standard reference and reported as a T-score. A T-score of -1.0 or above is normal; between -1.0 and -2.5 indicates low bone mass (osteopenia); below -2.5 is osteoporosis. DXA is simple, quick (10–20 minutes), and is the standard for diagnosing osteoporosis. Doctors typically recommend DXA scans for women over 65 and men over 70, or younger patients with risk factors like steroid use or a history of fractures. DXA helps predict fracture risk and guide treatment decisions (like starting bone-strengthening medication).

Some DXA machines also provide vertebral fracture assessment (VFA), which is essentially a lateral X-ray of the spine taken during the DXA test. VFA can reveal silent spinal fractures that a patient may not even notice. Another concept is the Trabecular Bone Score (TBS), a software tool applied to DXA images. TBS estimates the quality of the bone’s internal lattice (microarchitecture) rather than just density. A low TBS suggests weaker bone structure even if the density T-score is not in the osteoporotic range. Ultrasound bone density devices (like those measuring the heel bone) are available in some clinics as an initial screening tool, but they are not a substitute for DXA. They measure the speed of sound through bone, which correlates with density.

Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) is another density test that uses CT images to calculate bone mineral density (usually of the spine) in three dimensions. QCT can measure the trabecular bone density separately, but it involves higher radiation and is not as commonly used as DXA. Emerging technologies are also being developed to assess bone quality. High-resolution peripheral QCT (HR-pQCT) can take very detailed images of the wrist or ankle bone microarchitecture, though currently mostly in research. MRI-based techniques can assess bone marrow fat content as a proxy for bone health. Overall, these densitometry methods complement conventional imaging. A patient may have an X-ray or MRI for pain, and a separate DXA scan to gauge fracture risk. Knowing bone density helps doctors decide on prevention or treatment strategies for osteoporosis.

Nuclear Medicine Bone Scans

Nuclear medicine offers unique functional imaging of bone metabolism. The most common test is the bone scan (radionuclide bone scintigraphy). In this test, a small amount of radioactive tracer (usually technetium-99m attached to a phosphate molecule) is injected into the bloodstream. The tracer travels throughout the body and accumulates in areas of active bone remodeling – regions where bone cells are building or repairing bone. After a few hours, a special camera (gamma camera) scans the body to detect the tracer. On the images, areas with higher tracer uptake appear as “hot spots,” while areas with low uptake appear “cold.”

Bone scans can cover the entire skeleton and are very sensitive to abnormalities. They are often used to detect bone metastases (cancer spread to bone), bone infections (osteomyelitis), unexplained bone pain, or stress fractures not seen on X-ray. A single hot spot on a bone scan may indicate a localized problem like a fracture or tumor, whereas a pattern of multiple hot spots may indicate widespread disease. Bone scans are incredibly good at finding even small or early bone lesions anywhere in the body. However, they have low specificity: many different conditions (cancer, arthritis, infection, injury) can all cause increased uptake. Therefore, abnormal findings on a bone scan usually need correlation with other imaging (like X-ray or MRI) or clinical information.

Bone scintigraphy can be done in specialized ways. In a three-phase bone scan, the first images are taken immediately as the tracer is injected to assess blood flow, the second set a few minutes later shows tracer pooling in the soft tissues, and the third set hours later shows tracer uptake by bone. This technique helps differentiate bone infection from simple arthritis: an infection will show increased uptake on the first (blood flow) phase and second (soft tissue) phase, whereas a typical fracture or arthritis might not. In cases of suspected bone infection (osteomyelitis), doctors may also use labeled white blood cell scans. A small sample of the patient’s white blood cells is tagged with a tracer and reinjected; these cells then migrate to infected bone, causing those sites to glow on the scan. This is helpful for tricky cases like diabetic foot infections or post-operative complications.

Modern imaging often combines techniques. SPECT (single-photon emission computed tomography) rotates the gamma camera around the patient to create 3D images of tracer distribution. When SPECT is combined with CT (SPECT/CT), it provides precise anatomical localization of the hot spots. This hybrid imaging allows doctors to see exactly which bone or joint corresponds to the tracer uptake, improving diagnostic accuracy.

PET and SPECT in Bone Imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) is another type of nuclear imaging sometimes used for bone. The most common PET scan uses FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) to look for metabolically active cancer cells, which can also detect bone metastases. A newer agent, Fluoride-18 (¹⁸F) PET is very sensitive for bone turnover and can image bone metastases with high resolution; however, it is less widely available. PET scans are expensive and involve radiation, but they can cover the whole body quickly and find occult lesions. PET/CT machines combine metabolic imaging (PET) with a CT scan in one session. This allows oncologists to stage cancer by identifying bone lesions (hot on PET) and seeing their exact location on CT.

Single-photon emission CT (SPECT) using the same Tc-99m tracers as a standard bone scan can produce 3D images of specific areas (for example, to evaluate a painful joint or spine segment) with better localization. Some modern systems even combine SPECT and PET data with CT. In summary, nuclear medicine is invaluable for functional bone imaging, especially in oncology and unexplained bone pain. The cost and use of radioactivity are considerations, so these scans are ordered selectively by specialists.

Comparing Bone Imaging Methods

- X-ray (Radiography): Advantages: Very fast, widely available, excellent for detecting clear fractures and bone alignment. Disadvantages: Uses radiation (though low dose), provides only 2D images, and may miss small or complex fractures.

- CT (Computed Tomography): Advantages: Provides detailed 3D images of bone, great for complex fracture assessment and surgical planning, widely available in trauma centers. Disadvantages: Higher radiation dose than X-ray, expensive, and less detail on soft tissues.

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Advantages: No radiation, excellent soft tissue and marrow contrast, detects bone marrow edema and occult fractures, useful for joints and spine. Disadvantages: Time-consuming, expensive, cannot be used with some metal implants, and cortical bone is not directly imaged.

- Ultrasound: Advantages: No radiation, portable, excellent for assessing tendons and joints around bone, and guided procedures. It can screen bone density (at the heel) without X-rays. Disadvantages: Cannot image deep bone structures well, operator-dependent (image quality relies on the skill of the user), and is limited by bone curvature and air.

- Bone Scan (Scintigraphy): Advantages: Very sensitive for metabolic activity in bone, can image the whole skeleton for fractures, infection, or cancer spread. Disadvantages: Uses radioactive tracer, low specificity (needs correlation with other imaging), and usually requires multiple appointments (injection and delayed imaging).

Bone Imaging Across Medical Fields

Bone imaging technology plays an important role in many areas of healthcare. In orthopedics, X-rays and CT scans are essential to evaluate fractures, plan joint replacements, and diagnose conditions like spinal scoliosis or bone deformities. Rheumatologists often use ultrasound and MRI to visualize joint inflammation and bone erosion in arthritis. In sports medicine, MRI is frequently used to assess bone bruises, ligament injuries, and stress fractures in athletes, while ultrasound allows dynamic assessment of tendons and joints during movement.

Oncology relies on bone imaging for cancer staging and surveillance. Primary bone cancers (like osteosarcoma) and cancers that commonly spread to bone (such as breast, prostate, and lung) require scans to find metastases. Bone scans, PET/CT, CT, or MRI are used to detect and monitor these lesions. Dentists and oral surgeons depend on dental X-rays and cone-beam CT to plan implants, detect jaw cysts or tumors, and assess the sinuses and airway.

Even outside of medicine, bone imaging principles are applied in forensics and archaeology. Investigators use X-ray or CT to examine skeletal remains, looking for evidence of trauma or disease in historical specimens. Researchers and engineers use micro-CT scans to study the fine internal structure of bone grafts, scaffolds, and new biomaterials.

This wide range of applications underscores that bone imaging is a foundational tool across science and healthcare. As technology advances, its integration into more fields will continue, ultimately improving patient outcomes in many areas of care.

Choosing the Right Imaging Technique

Selecting the appropriate imaging modality depends on many factors. Some major considerations include:

- Clinical need: What problem is being investigated? For example, suspected fracture vs. joint pain vs. cancer screening will guide the choice.

- Body area: Different modalities excel at different parts of the skeleton. For example, spine injuries might need CT or MRI, while a broken wrist can often start with X-ray.

- Radiation exposure: When possible, imaging specialists try to minimize radiation. Children and pregnant women are especially protected. If bone imaging is needed repeatedly, non-ionizing options (ultrasound, MRI) are preferred.

- Speed and cost: X-rays are quick and inexpensive, suitable for most initial assessments. CT is fast for emergencies. MRI takes more time and is more expensive, so it is reserved for specific questions.

- Availability: Not all hospitals have advanced scanners. Doctors often start with the simplest useful test available, then escalate as needed.

- Patient condition: Very ill or unstable patients may only tolerate quick scans. MRI requires patients to lie still, which may need sedation for some children or anxious patients.

- Previous imaging: Sometimes earlier scans (X-ray or CT) show enough detail, and further imaging might not be needed unless new symptoms arise.

Examples of modality selection include:

- A patient with a twisted ankle and visible bruising: an X-ray of the ankle (front and side views) is usually the first step, as it quickly identifies most bone breaks in that area.

- Someone with chronic wrist pain and normal X-rays: consider MRI or CT to look for a small fracture or soft tissue injury.

- A middle-aged person with suspected osteoporosis but no pain: a DXA scan of the hip and spine is appropriate rather than any diagnostic X-ray.

- An athlete with recurrent knee pain: MRI is favored to see ligaments, cartilage, and bone marrow details that X-ray cannot show.

- A cancer patient with bone pain: a whole-body bone scan or PET/CT may be done to look for metastases throughout the skeleton.

- A child under 12 months with suspected hip dysplasia: ultrasound is used because the hip bones are not fully ossified yet.

- An urgent head injury with possible cervical spine trauma: CT of the spine is done immediately because it is fast and sensitive to fractures.

Safety and Patient Considerations

Every imaging study balances information gained with safety and comfort. The following safety measures are commonly used:

- Lead Shields: During X-ray or CT imaging, parts of the body not being scanned (like the abdomen or gonads) may be covered with a lead apron to reduce unnecessary exposure.

- Dose Management: Radiology departments carefully calibrate machines so that children and smaller patients receive less radiation. Modern CT scanners can automatically modulate the dose based on the patient’s size.

- MRI Precautions: Patients are screened for any metal implants. All metal objects (phones, watches, jewelry, credit cards) must be left outside the scan room. Ear protection (plugs or headphones) is given to reduce the loud noise.

- Contrast Safety: If iodine or gadolinium contrast is used, patients are asked about kidney function and allergies. Emergency equipment and medication are always available in case of a rare reaction. Patients are advised to stay hydrated to help flush contrast agents out of their system.

- Pregnancy and Children: Imaging of pregnant women is minimized unless essential. Ultrasound and MRI are preferred in pregnancy. For children, pediatric imaging protocols and often sedation (for MRI) are used to ensure images are obtained without repeat exposures.

- Patient Comfort: When possible, patients are allowed to eat and drink before certain scans, or given an IV if needed. Communication systems (microphone, buttons) are provided so patients can talk to the technologist during MRI or CT if they feel anxious.

For example, always inform your doctor if you are pregnant or think you might be pregnant before any scan involving X-rays or CT. Remove all metal objects (jewelry, watches, etc.) before an MRI. Be sure to share your full medical history, including any past reactions to imaging contrast agents. Technologists and radiologists follow strict guidelines to ensure that each scan is as safe as possible while still providing needed diagnostic information.

The Future of Bone Imaging

Bone imaging technology continues to evolve rapidly. Artificial intelligence (AI) is set to transform bone imaging. Software is now being trained to automatically detect common fracture sites (like the hip or wrist) on X-ray and measure angles in bone images, potentially helping screen for osteoporosis or alignment issues. Radiomics is a field where computers analyze images for complex patterns. Research shows radiomic features from a routine CT scan (such as texture patterns in vertebrae) can predict fracture risk or bone quality. In practice, AI might soon assist radiologists by flagging subtle fractures or analyzing bone density on any scan a patient gets, adding valuable information with minimal extra effort.

Photon-counting CT is an emerging technology that may improve bone imaging. Traditional CT combines all X-ray photons at a detector, but photon-counting detectors register each photon separately by energy. This leads to sharper images with less noise. In practice, photon-counting CT may allow seeing finer bone details (like tiny trabeculae) at lower radiation doses. It also can distinguish materials better, which could improve identification of bone composition or metal implants.

Augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR) tools are being developed to use bone imaging data. For instance, 3D scans of a patient’s pelvis can be turned into a VR model so a surgeon can “walk around” a fracture before operating. AR overlays might allow a surgeon to see a patient’s CT images projected onto their body during surgery. These are active research areas aimed at increasing the precision of orthopedic procedures.

Other research involves molecular imaging agents: particles that bind to bone cells or matrix and emit signals detectable by MRI or fluorescence. Such techniques could one day show us not only bone structure but also cellular activity (like the sites of bone formation or early metastasis) in living patients. For example, fluorescent markers that attach to active bone-forming cells are being studied in animal models. While not yet in routine use, this line of research underscores that bone imaging technology continues evolving toward a more complete picture of bone health and disease.

A newer X-ray technology known as EOS imaging can capture full-body, 3D skeletal images while the patient stands naturally. It uses very low radiation and is often used for conditions like scoliosis or spine deformities where alignment in a weight-bearing position is important. EOS can measure spinal curvature, leg lengths, and joint angles accurately, assisting surgeons in planning realignment procedures. This technology bridges traditional X-ray and 3D modeling for bone alignment assessment.

Follow-Up and Patient Management

Bone imaging is not only for initial diagnosis; it often guides follow-up care. Doctors often follow standard timing for scans after treatments. For instance, a fracture that is treated without surgery might be rechecked with X-ray after 4–8 weeks to ensure the bone is healing properly. After surgical fixation (like plates or screws), an immediate postoperative X-ray confirms hardware placement, and another scan may be done a few months later to confirm union. In bone tumor care, periodic MRI scans (for example every 3–6 months) may be used to detect any recurrence early.

Patients should also be aware that the information from bone imaging can guide lifestyle and medical decisions. If a bone density scan shows osteoporosis, a doctor may recommend medications or supplements, plus weight-bearing exercise to strengthen bones. If a tumor is detected, imaging helps plan surgery or radiation therapy. The synergy between imaging findings and patient care is why these scans are a powerful tool in management.

Bone imaging technology offers powerful tools for doctors to diagnose and manage skeletal health. As new technologies like AI analysis, hybrid scanners (such as PET/MRI), portable imaging devices, and smart contrast agents arrive, patients will have more options and clinicians will have more information than ever to care for bone conditions. With each advance, bone imaging technology continues to open new possibilities for care, making diagnoses more accurate and treatments more effective. Staying informed about these imaging techniques can help patients and healthcare providers work together for the best outcomes in bone health and mobility.