The process of bone repair is a complex interplay of biological and mechanical factors. When a fracture occurs, the body initiates a finely tuned cascade of events to restore the structural integrity of the damaged bone. In many cases, this process proceeds uneventfully, leading to successful consolidation. However, various complications such as delayed union, nonunion, malunion and post-surgical infection can disrupt normal healing. Understanding the underlying mechanisms, identifying risk factors and implementing effective prevention strategies are essential for improving patient outcomes and reducing the burden of chronic disability.

Etiology and Risk Factors

Bone healing complications arise from a combination of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include patient-specific characteristics such as age, metabolic status and comorbidities. Extrinsic factors involve the nature of the injury, quality of initial fixation and post-operative management. The following key elements contribute to risk:

- Poor vascular supply at the fracture site impairs nutrient delivery and osteogenesis.

- High-energy trauma can damage surrounding soft tissues, leading to extensive inflammation and scarring.

- Unstable mechanical environment due to inadequate fixation or early weight-bearing disrupts callus formation.

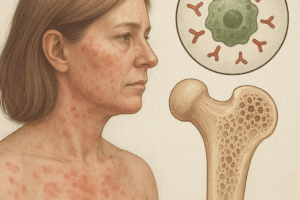

- Systemic conditions like diabetes, osteoporosis and smoking decrease bone regenerative capacity.

- Use of certain medications, for instance nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or corticosteroids, may inhibit key cellular signaling pathways.

Furthermore, local infection represents a major hurdle in the repair continuum. Bacterial colonization of implants or fracture hematomas delays progression beyond the inflammatory phase and often necessitates aggressive surgical debridement combined with prolonged antibiotic therapy. Combatting infection requires meticulous surgical technique, perioperative prophylaxis and close post-operative surveillance.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Early identification of compromised healing is paramount for timely intervention. Clinicians monitor both clinical signs and radiological evidence to determine the healing trajectory. Typical markers of normal progression include decreasing pain, callus formation on imaging and incremental restoration of function. In contrast, warning signs of complication encompass persistent pain at the fracture site, abnormal motion or tenderness, and absence of radiographic bridging after expected time periods.

Radiographic Assessment

Standard radiographs remain the cornerstone of follow-up evaluation. Delayed union is often defined by lack of sufficient callus after six months, while nonunion may be diagnosed if healing fails by nine months. Advanced imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) can offer detailed three-dimensional views of cortical continuity and hardware positioning.

Laboratory and Functional Testing

When infection is suspected, laboratory markers like elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) support clinical suspicion. Joint aspiration or deep tissue biopsy helps isolate pathogens. Functional assessments, including gait analysis and force measurement, gauge patient progress and guide decisions on weight-bearing restrictions or modification of fixation strategies.

Prevention Strategies and Therapeutic Approaches

Preventing bone healing complications requires a multidisciplinary approach that addresses mechanical, biological and patient-related factors. Treatment algorithms often integrate conservative and surgical interventions tailored to individual risk profiles.

Optimization of Mechanical Stability

Appropriate selection of fixation devices—such as plates, intramedullary nails or external frames—ensures adequate stiffness and alignment. The concept of biomechanics underpins device choice: stable constructs promote direct healing, while controlled micromotion can stimulate callus formation via secondary repair pathways.

Enhancing Biological Environment

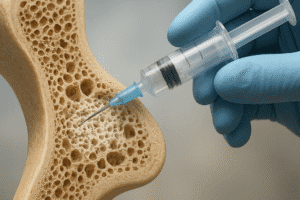

Biological adjuvants aim to boost the regenerative milieu. Strategies include:

- Autologous bone grafts rich in osteoprogenitor cells and growth factors.

- Allogeneic or synthetic bone substitutes providing osteoconductive scaffolds.

- Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and recombinant growth factors to accelerate mineralization.

Emerging cell-based therapies utilize mesenchymal stem cells to enhance tissue repair. Such approaches strive to restore the delicate balance of osteoblast and osteoclast activity essential for remodeling.

Systemic and Nutritional Management

Patient optimization includes correction of nutritional deficits—particularly adequate protein, calcium and vitamin D intake—and control of metabolic disorders. Smoking cessation and glycemic regulation in diabetic patients significantly improve healing times. Personalized rehabilitation programs focus on gradual load progression, muscle strengthening and rehabilitation to preserve range of motion without compromising fixation.

Emerging Technologies in Bone Repair

Advancements in materials science and bioengineering are redefining the future landscape of fracture management. Innovations under investigation include:

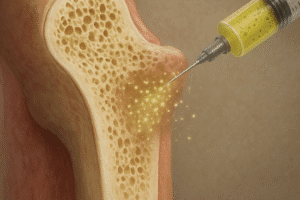

- Smart implants with embedded sensors to monitor real-time mechanical environment and detect early signs of loosening or infection.

- 3D-printed scaffolds customized to patient anatomy, promoting optimal integration and vascular ingrowth.

- Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems offering targeted release of antibiotics or osteoinductive molecules at the fracture site.

These cutting-edge modalities hold promise for reducing complication rates and facilitating personalized care pathways. However, rigorous clinical trials are needed to validate long-term safety and cost-effectiveness.