Maintaining robust skeletal health goes beyond regular exercise and sunlight exposure. The intricate balance of nutrients, hormones, and cellular processes is fundamental for preserving bone density and preventing disorders such as fractures and chronic weakness. In this article, we delve into the critical elements of nutrition that support strong bones and explore how deficiencies can undermine skeletal integrity.

Understanding the Foundation of Healthy Bones

Bone is a living tissue, continuously undergoing remodeling through the coordinated actions of osteoblasts (cells that build bone) and osteoclasts (cells that break down bone). This dynamic process ensures skeletal strength and adaptability. Key components of bone include a mineralized matrix and a protein scaffold that work in unison to provide both hardness and flexibility.

Mineral Matrix and Organic Scaffold

The inorganic portion of bone is composed primarily of hydroxyapatite crystals, which derive from essential minerals. The organic framework is dominated by collagen, a fibrous protein that gives bones tensile strength. Disruption in the availability or assembly of these elements compromises bone resilience and increases susceptibility to fractures.

Bone Remodeling Dynamics

Bone remodeling involves coordinated signaling pathways that regulate formation and resorption. Hormones like parathyroid hormone and vitamin D metabolites fine-tune this balance. When nutrient supply falters, the remodeling cycle becomes skewed, leading to diminished bone mass and architecture. This imbalance is a hallmark of conditions such as osteoporosis and other metabolic bone disease states.

Key Nutritional Deficiencies That Weaken Bones

Several nutrients are indispensable for optimal bone health. Insufficient intake or impaired nutrient absorption can lead to structural weakness and elevate fracture risk. Below, we outline the most common deficiencies linked to compromised skeletal strength:

- Calcium: The cornerstone of bone mineralization. Chronic low intake triggers release of calcium from the skeleton to maintain blood levels, eroding bone density over time.

- Vitamin D: Crucial for intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. A deficit results in inadequate mineral deposition and can cause rickets in children or osteomalacia in adults.

- Phosphorus: Works synergistically with calcium to form hydroxyapatite. Although abundant in many foods, excessive intake of certain antacids or underlying kidney disorders can disrupt phosphorus balance.

- Magnesium: Participates in crystal formation and modulates parathyroid hormone secretion. Low levels impair bone structure and may heighten inflammatory responses.

- Vitamin K: Facilitates carboxylation of osteocalcin, a protein integral to bone mineralization. Deficiency can lead to poor bone matrix quality and increased fracture risk.

- Protein: Provides amino acids for collagen synthesis and supports growth factors. Both inadequate and excessive protein intake can adversely affect bone remodeling.

- Trace elements (e.g., zinc, copper, manganese): Act as cofactors for enzymes involved in matrix production. Even mild shortages can subtly impede bone strength over years.

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Possess anti-inflammatory properties that may protect against bone resorption. Low dietary intake can exacerbate chronic inflammation and bone loss.

Clinical Manifestations of Nutrient-Related Bone Loss

Failure to address nutrient gaps may present with overt and subclinical signs. Early recognition allows timely intervention and prevents irreversible damage.

Childhood Rickets and Delayed Growth

Inadequate vitamin D and calcium during skeletal development impairs proper mineralization, leading to soft, pliable bones. Clinically, this manifests as bowed legs, delayed motor milestones, and dental defects.

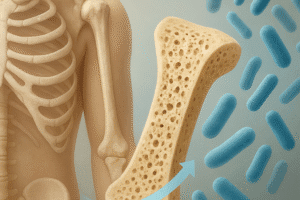

Adult Osteomalacia and Osteoporosis

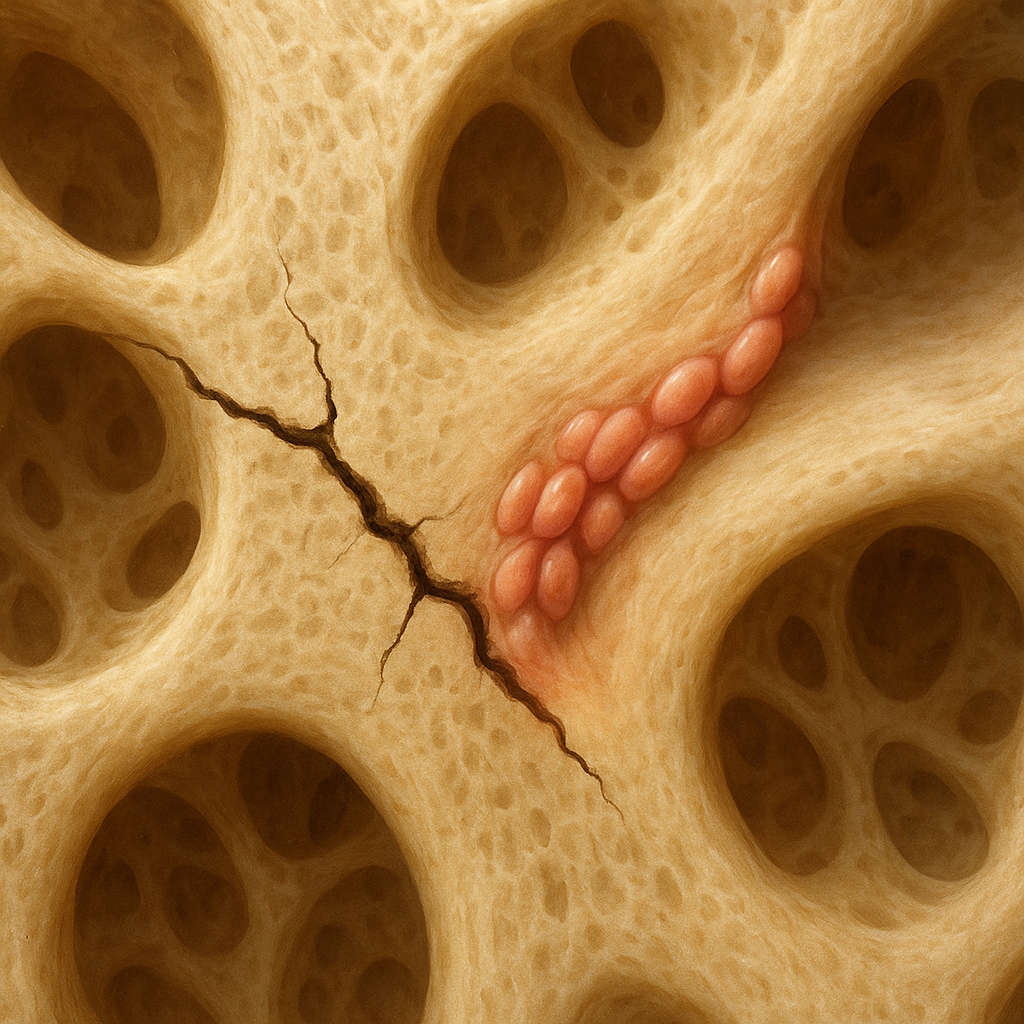

- Osteomalacia: Characterized by defective mineralization in adults, causing bone pain, muscle weakness, and increased fracture risk.

- Osteoporosis: A systemic skeletal disorder marked by reduced bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration. Often asymptomatic until a low-impact fracture occurs.

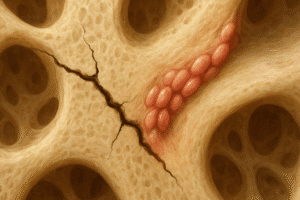

Fracture Healing Complications

Optimal bone repair demands sufficient supplies of calcium, phosphorus, and protein. Deficiencies prolong healing times and may result in nonunion or malunion, especially in the elderly or individuals with chronic illnesses.

Strategies to Prevent and Correct Nutritional Deficiencies

Implementing dietary and lifestyle modifications can safeguard bones throughout life. Personalized interventions often yield the best outcomes.

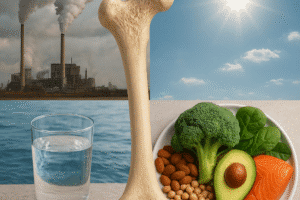

Dietary Optimization

- Include dairy or fortified plant-based alternatives to boost calcium intake.

- Encourage fatty fish, egg yolks, and UV-exposed mushrooms for adequate vitamin D status.

- Incorporate whole grains, nuts, seeds, and leafy greens to supply magnesium and phosphorus.

- Add fermented foods (e.g., natto, sauerkraut) for natural sources of vitamin K.

- Balance protein from diverse sources—legumes, lean meats, dairy—to support collagen formation.

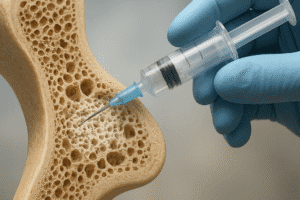

Supplementation and Pharmacotherapy

When dietary adjustments prove insufficient, targeted supplements can correct deficiencies. Strategies may include:

- Daily or weekly vitamin D3 supplements, calibrated by serum 25(OH)D levels.

- Calcium citrate or carbonate supplements, timed with meals for optimal absorption.

- Magnesium glycinate or citrate to enhance bioavailability and minimize gastrointestinal side effects.

- Vitamin K2 supplements to support bone matrix quality.

Lifestyle and Functional Measures

Physical activity exerts mechanical stress on bone, stimulating bone remodeling and enhancing mineral deposition. Resistance training, weight-bearing exercise, and balance activities reduce fall risk and strengthen the musculoskeletal system.

Maintaining healthy body weight, avoiding smoking, and limiting excessive alcohol consumption further supports nutrient metabolism and skeletal integrity.